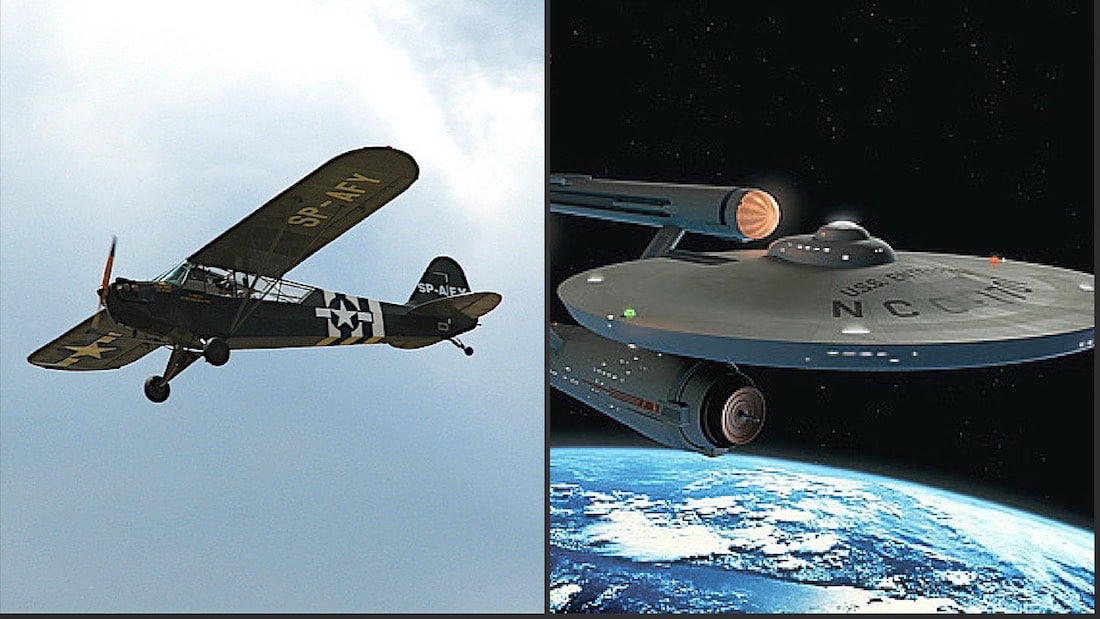

From the J3 Cub to the USS Enterprise: The True Story of Gene Roddenberry and his time in aviation.

“When you get into an airplane by yourself and take off, you find yourself in this lovely, three-dimensional world where you can go in any direction. There is no feeling any more exciting than that.”

-Gene Roddenberry

Most of us know Gene Roddenberry as the creator of the Star Trek franchise. Cherished around the world for decades as a symbol of humanity’s unlimited potential and the countless adventures that await us in the cosmos, Star Trek has become a cornerstone of popular culture, inspiring many people to pursue careers in the aviation and aerospace industries.

Interestingly, the connection between the show’s creator and the world of flight and aviation runs much deeper than one might think. Gene Roddenberry was a decorated pilot, flying both combat missions piloting the B-17 Flying Fortress during World War II and for the airlines after the war.

The egalitarian spirit that continues to animate Star Trek is one that Roddenberry took to heart, and is one of the reasons for the popularity and lasting legacy of the series. The idea of exploring the galaxy and giving aid to other worlds, cultures, and peoples is one that many pilots aspire to. It represents the best about humanity.

And Roddenberry didn’t just preach – he practiced. One fateful night, in particular, would change his life forever and show the world a glimpse of the man who would help change the way we view human cooperation and social progress.

Second Lieutenant Eugene Wesley Roddenberry

Born in El Paso, Texas and raised in Los Angeles as the son of a police officer, Gene Roddenberry became infatuated with science fiction and space travel at an early age. He read all the popular science fiction of the time, like John Carter of Mars and the Skylark series. This early fascination with space exploration and adventure would remain with Roddenberry for the rest of his life.

After high school, he began pursuing a far more grounded career. Following in his father’s footsteps, he enrolled in the police sciences program at Los Angeles City College. And though he majored in police science, he was unable to shake his love for flying and exploration and soon began playing with the idea of studying aeronautical engineering.

Eventually, Roddenberry registered in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, sponsored by the US Army Air Corps, and obtained his pilot’s license. And on December 18, 1941, just days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Roddenberry enlisted in the Air Corps. He graduated with the rank of second lieutenant in August of the following year.

Roddenberry was posted to the 394th Bomb Squadron stationed out of Oahu, Hawaii, where he piloted the iconic Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. He participated in the pivotal invasion of Guadalcanal and flew bombing raids from the newly-captured Japanese airstrip, helping to cement the American victory over the island. While in the South Pacific, Roddenberry also began writing, selling stories to aviation magazines and even The New York Times.

In August of 1943, a plane Roddenberry was piloting overshot the runway and crashed. An official report absolved him of any responsibility, but after this accident, Roddenberry was reassigned to the states. Here, he served the military for two more years as a plane crash investigator. During this time, he was involved in a second crash, this time as a passenger. For his service in the military, Roddenberry was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal.

Civilian Life and Traveling the World

After the war, Gene Roddenberry became an airline pilot, signing up with Pan American World Airways, the country’s largest air carrier at the time. He would often be tasked with flying passenger routes from New York to Johannesburg or Calcutta, the airline’s two longest routes at the time.

While spending his professional life in the sky – Roddenberry would fly for Pan Am for four years – he continued to pursue his love of storytelling. He studied writing at Columbia University and continued selling short stories and poetry.

The Fateful Night That Would Change Gene Roddenberry’s Life

On June 18, 1947, Roddenberry was on Pan Am Flight 121 from Calcutta to New York, onboard the Clipper Eclipse, a Lockheed L-049 Constellation passenger aircraft. Gene Roddenberry was “deadheading,” meaning he’d been re-positioned from flight crew to a passenger for at least this segment of the flight. The flight left Karachi for Istanbul, the next stop on the flight, at 3:37 PM. They were expected to make Istanbul at 2:08 the following morning. However, five hours after takeoff, engine one on the left wing stopped working after a rocker arm broke from fatigue.

Flight 121’s captain, Joesph Hart, feathered1 the propeller and assessed the situation. After noting that the available airports along the route were either closed or had inadequate repair facilities, Hart decided to push on to Istanbul on three engines. However, at a cruising altitude of 18,500 feet, the current airspeed could not sufficiently cool the engines. Power was reduced, but even at 17,500 feet, the engine still began overheating. The plane continued to descend.

At 9:40 PM, about an hour after engine-one quit, Captain Hart advised the Pan Am offices in Karachi of their engine trouble. He reported the current altitude at 14,000 feet and their position as 50 miles east of Baghdad. Shortly after 10 PM, they radioed Habbaniya Tower at the Royal Air Force Field in Iraq, 40 miles to the east. They reported their position over Baghdad, at an altitude of 10,000 feet and requested the tower inform the civilian airfields in the area that they were continuing to Istanbul on three engines. Habbaniya Tower replied that no airfields would be open until dawn, and advised them to change course and make an emergency landing at Habbaniya.

Flight 121 restated their intention to push on for Istanbul, adding that if became impossible to reach their intended destination, they would make an emergency landing at Damascus, in Syria. Shortly after this, Habbaniya Tower radioed Flight 121 and let them know all airfields in Damascus were closed until 4 AM, and again recommended an emergency landing at Habbaniya. Flight 121 again stated they would push for Istanbul, but did say they would turn back and head for Habbaniya if they encountered further engine trouble.

At the same time, Flight 121 relayed a message to Damascus, through Karachi, to open the airport and standby in case of emergency. Damascus received the message and opened the airport shortly after 11 PM.

Suddenly, without warning, engine two, also on the left wing, burst into flame2, filling the entire aircraft’s cabin with red light. Flight 121 reported the fire to Habbaniya at 11:30 PM, reporting a position 170 miles Northwest of Habbaniya and 290 miles northeast of Damascus. Immediately after this, Captain Hart began a rapid descent toward the desert below, with the intention of crashlanding the aircraft.

Several minutes later, while on approach for the landing, the burning engine 2 broke away from the airplane wing with a sickening crunch. Pan Am stewardess Jane Bray recalls this moment:

“I looked out. The number 2 motor was all afire and it seemed to have spread to the wing. I wondered why they didn’t drop that motor. I looked up and even through the fire, I could see bright stars. But everything else was black as pitch. Suddenly there was a hard jar, just like when a tooth is pulled and you feel it crunch. The burning motor had fallen loose.”

Less than a minute after engine two broke off from the wing, Captain Hart successfully executed a wheels-up crash landing on the relatively smooth hard-packed desert sand close to the banks of the Euphrates river.

The left wing tip hit the ground first, followed by the propeller on engine one and then the body of the left wing. The impact violently ripped the left wing from the fuselage of the plane, which in turn caused it to ground loop hard to the left. Again, Bray recalls the moment:

“We hit hard on the belly with an awful jar which would not stop. We slid across the sand. The plane swung hard around to the left and split in two, pretty well forward. Flames poured in and the heat became terrific.”

While caught in the ground loop, the plane turned 180 degrees and slid backward some 200 feet before coming to rest roughly 400 feet from the first point of impact. The flaming, wrecked Clipper Eclipse was now pointed in the direction opposite of when it landed.

As soon as the aircraft came to rest, Gene Roddenberry, suffering only bruises and a couple broken ribs, sprang into action. Aided by Bray and chief flight attendant Anthony Volpe, they began evacuating passengers as quickly as they could, the flames continually growing in size and intensity. After forcing open the cabin door and guiding the uninjured passengers out, Roddenberry and Volpe began handing down the injured passengers. Bray and the uninjured passengers then helped carry or drag them to safety.

One passenger, Indian royal Majarani of Pheleton, was trapped in the burning fuselage by her seat belt, hysterically thrashing around. Roddenberry calmed her down, forced the seat belt open, and helped her evacuate the wreckage. As Roddenberry continued pulling passengers free, several were on fire. He used a pillow he found on the ground to smother flames as best he could before passing them out of the wreckage.

The flames continued growing in intensity, but Roddenberry made another trip into the passenger area. However, as he was pulling a final passenger free from the wreckage, the person died in his arms. Even worse, the wind suddenly changed direction, blowing gasoline over the passenger area and engulfing it completely in flames. Roddenberry and Volpe were not able to rescue any other passengers.

The trio then turned their attention to the crew in the flight deck. They raced around the burning fuselage and wing to the front of the plane, only to be greeted by a terrible site. They could see through the cockpit window that Captain Hart and the rest of the flight crew were at their stations, slumped over in their seats. They were either unconscious or dead. They attempted to gain access to the cockpit but were ultimately pushed back by the flames.

8 passengers and 7 crew members were killed in the crash and ensuing fire. Roddenberry, Volpe, and Bray were the only crew to survive, and due to their heroism, 19 passengers survived as well.

As the sun rose, Roddenberry directed two English passengers to swim across the Euphrates and head towards some lights he’d seen as the plane had been descending for the crash landing. The lights turned out to be a Syrian military outpost, and they sent a small airplane back to the crash site to investigate. Roddenberry flew back to the outpost with the small plane and radioed a report to Pan Am, who sent out a stretcher plane to rescue the survivors of the crash. For his efforts during this event, Roddenberry was awarded a Civil Aeronautics commendation.

Life After Flying

Perhaps surviving three crashes was enough flying for Gene Roddenberry, and on May 15, 1948, he resigned from his position at Pan Am. He was interested in pursuing his passion for writing, especially for the brand new medium of television. However, as television was still in its infancy, he wasn’t able to make enough of a living writing, so he joined the Los Angeles Police Department on January 10, 1949. He served there for seven years before resigning from the force when his writing career finally took off.

Over the next 8 years, he wrote for a variety of shows, including an award-winning episode of Have Gun, Will Travel. Finally, in 1964, after being turned down by MGM and CBS, he was able to sell the idea of Star Trek to NBC. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Gene Roddenberry: A Pilot’s Duty

Whether piloting a B-17 Flying Fortress or an airliner, Gene Roddenberry demonstrated to the world a fundamental tenet of aviation: a pilot’s first duty is to his passengers. While the joy of flying is a reward in and of itself, student pilots and veterans alike should take inspiration from Roddenberry’s example, putting the lives of those under their care above all other considerations.

June 18, 1947, was a turning point in Gene Roddenberry’s life. It reinforced his long-held belief that cooperation is always more productive and rewarding than a competition and that every human being has the capacity to act selflessly, for the benefit of all. While the rest of us will hopefully never have to undergo such a traumatic test of our courage and selflessness, we can take Roddenberry’s philosophy to heart, and work to consider the safety, happiness, and comfort of those around us before our own.

Footnotes:

1 – On some variable pitch propellers, the blades can be rotated so they are parallel to the airflow in case of an engine failure. This reduces drag and helps the airplane maintain altitude while operating on reduced power from the remaining engines.

2 – It was later reported that the engine’s thrust bearing failed, which blocked the passage of oil between components in the engine, eventually leading to the fire.

Sources:

//www.planecrashinfo.com/1947/1947-42.htm

//www.check-six.com/Crash_Sites/ClipperEclipse-NC88845.htm

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_Roddenberry

//roddenberryfoundation.org/

//www.snopes.com/roddenberry-plane-crash/

I had heard the Enterprise’s number NC-1701 was named after an aircraft and always wondered what type of aircraft.

Ed,

Good question! Here’s what I could find about the registration code “NCC-1701” for the Enterprise. As I understand it, Matt Jefferies, the art director for the original Star Trek series and primary designer of the enterprise, gave it that number. Jefferies was a pilot, and the “NCC” part of the code was indeed inspired by aircraft codes. The “N” comes from the fact that “N” is the international aircraft code assigned to the US. Pre-1950s, the “N” was occasionally paired with a second letter to identify the category of the aircraft, in this case, “C” for civil or standard. The second “C” was added to make it different. Also, in “The Making of Star Trek,” it was said that NCC stands for “Naval Construction Contract,” and paired with the number that follows is the Starfleet equivalent of a Navy hull number. As for the selections of 1701, there are a few competing theories:

1 – The most accepted version is that Jefferies selected “1701” to avoid ambiguity, as the numbers 3, 6, 8 and 9 can be more easily confused. The design selected was also the 17th he’d sketched (or the 17th version “designed” by Starfleet), and the Enterprise was the first model of that series, or 01.

2 – Other sources say that it’s a reference to a house across the street from where Gene Roddenberry grew up.

3 – Finally, there are claims that “1701” is a reference to the street number where visual effects artist and pioneer Linwood Dunn, who worked on everything from King Kong to Citizen Kane and the original Star Trek series, grew up.

So, sadly, it appears that it was not coded / named after a specific aircraft, but rather the code was simply inspired by aviation in general.

My Sister in law, Jane Bray, was the stewardess on this flight. Thank God, she survived the crash.