Have I ever witnessed a fully loaded passenger jet takeoff without clearance, like the Tenerife Airport Disaster? Yes.

There’s another Captain Jacob Van Zanten flying out there somewhere, right now.

If his name doesn’t ring a bell, the crash that killed him, the one he’s blamed for, just might: Tenerife. It remains to this day the world’s most deadly airline accident, with 583 lives lost. March 27 marked the 40th anniversary of the infamous epic ground collision between two jumbo jets on a runway at Tenerife, in Spain’s Canary Islands, off the coast of West Africa.

Perhaps no airline captain in modern history has been more uniformly vilified than KLM Captain Jacob Van Zanten. There is no dispute among investigators that ultimately, the cause of the tragedy rests squarely on Van Zanten’s shoulders. But perhaps if we sift through the carnage again, it yields clues worth examining. Insights into Van Zanten’s actions, and more importantly, maybe even into our own mission-oriented pilot mentality.

Reviewing the Tenerife Airport Disaster

Let’s revisit the confounding day. Van Zanten is at the helm of the KLM Royal Dutch Airlines flight from Amsterdam, on its way to the Canary Islands. The Pan Am jet is enroute from Los Angeles after a stop in New York. Both flights are charters, carrying primarily cruise ship-bound vacationers.

Neither KLM nor Pan Am are even scheduled to land at Tenerife. What starts a cascade of seemingly insignificant events begins minutes earlier with a single act that ignites a small bomb. Not one person dies from the terrorist blast, but the event becomes the linchpin in a deadly chain reaction that will within hours kill 583 people.

The detonation occurs inside the passenger terminal at Las Palmas airport on Gran Canaria island, the scheduled destination of the two jumbo jets. Las Palmas airport temporarily closes, and both KLM, Pan Am, and a few other flights are diverted to nearby Tenerife, a larger island, but equipped with a smaller airport with a single runway.

After KLM and Pan Am land and wait on the congested, crowded ramp of Tenerife’s Los Rodeo airport, Captain Van Zanten thinks it might be wise to refuel. He’s calculating ways to save valuable time he might later need when dropping the passengers off at Las Palmas, and boarding a new load for the long flight home to Amsterdam. He calls KLM headquarters back in the Netherlands. They agree. Thousands of pounds of fuel begin pouring into Van Zanten’s Boeing 747.

As fate would have it, the destination airport, Las Palmas, suddenly reopens. Since refueling has already begun, Van Zanten elects to continue. It seems the logical thing to do. Unfortunately, this single act will soon haunt him in the final moment of his life, when he will try in vain to lift his lumbering, loaded 747 off the runway and over the Pan Am jet before they collide.

Van Zanten knows time is of the essence, and tension mounts.

Newly legislated Netherlands airline duty time regulations call for draconian penalties, up to and including imprisonment, for pilots who exceed the legal limitations. More issues accumulate. If the KLM flight gets stuck on Tenerife, will there be enough hotel rooms to accommodate the hundreds of passengers? What about the other crowd of passengers waiting to be picked up at Las Palmas? An expensive logistical nightmare looms as Van Zanten pushes to keep things moving.

During the time it takes to refuel, the weather seems to conspire, dropping the visibility precipitously low, a few hundred feet in some spots. American poet laureate Carl Sandburg once eloquently wrote, ‘The fog comes on little cat feet.’ But not at Tenerife. The volcanic island’s airport rises 2,000 feet above the surrounding ocean. More dramatic than fog, actual clouds roll in off the sea, diminishing clear skies to murk in only minutes.

Van Zanten is forced to taxi out in the soupy conditions, and commence a tight 180-degree turn at the end of the runway to line up for takeoff. The illuminated runway centerline lights that would normally aid a pilot are out of service. The turn maneuver requires perfect technique: a 142-foot turn radius on the 150-foot wide runway. Only eight feet to spare, to be executed from the towering vantage of the jumbo jet’s high crow’s nest cockpit.

The fog also makes it difficult for the Pan Am crew to see, as they creep along behind KLM, both invisible to each other and to the controllers in the small control tower. Pan Am misses its first turn – an almost impossible semi-backwards turn for a B747 – and aims for the next more favorably angled taxiway. That short taxiway will take them onto the longer parallel taxiway that leads to the end of the runway, to take off after KLM. More critically, it will get them off the active runway.

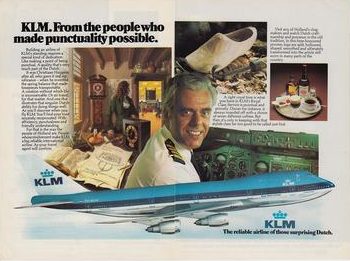

If any of Van Zanten’s passengers thumbed through the in-flight magazine as the big four engines roared to takeoff power, they would have seen the airline’s full-color two-page advertisement spread, extolling the Dutch history as timekeepers, and the KLM virtue of making schedules. The proud headline “KLM. From the people who made punctuality possible.” Next to it a photo of an archetypal handsome uniformed airline pilot, the company’s on-time poster boy, none other than Captain Jacob Van Zanten.

If any of Van Zanten’s passengers thumbed through the in-flight magazine as the big four engines roared to takeoff power, they would have seen the airline’s full-color two-page advertisement spread, extolling the Dutch history as timekeepers, and the KLM virtue of making schedules. The proud headline “KLM. From the people who made punctuality possible.” Next to it a photo of an archetypal handsome uniformed airline pilot, the company’s on-time poster boy, none other than Captain Jacob Van Zanten.

At this moment, he has his hands full, completing the tight turn in the heavy fog at the end of the runway. If the visibility continues to deteriorate below legal minimums he will have to delay. He begins to add power, alarming co-pilot Klass Meurs, who speaks up saying, ‘Wait…we do not have a clearance.’ Van Zanten retards the throttles to idle. Meurs then obtains the route clearance and reads it back over the radio to the air traffic controller.

KLM now has a flight plan clearance to their destination. But they do not have an actual clearance to takeoff. There is an exchange among the Spanish controller, the American Pan Am crew, and the Dutch KLM pilots. All are attempting aviation English over the air, but confusion reigns.

Van Zanten mistakenly takes the clearance as a signal that he is cleared for takeoff, and again applies power. The Pan Am crew recognizes something is amiss and nervously broadcasts that they are still on the runway. At that exact instant, the tower controller radios KLM to standby for takeoff. The two microphones, keyed at the same time, effectively cancel each other out with a squeal. Neither transmission is clearly heard by the KLM captain or copilot. Van Zanten does not know Pan Am is still on the runway, dead ahead.

But the KLM flight engineer, Willem Schreuder, a highly-experienced crewmember with over 17,000 hours, senses the uncertainty and asks, ‘Is he (Pan Am) not clear then?’ He states the question a second time. Van Zanten responds with an emphatic ‘Yes’ and by now KLM is picking up speed.

Van Zanten has lost all track of Pan Am’s location.

Further Exploring Van Zanten’s Role in the Tenerife Airport Disaster

What will always be the most vexing question surrounding Tenerife, is why. Not as in why didn’t he ‘know’ exactly where Pan Am was – the jet was impossible to see in the heavy fog. But as in why didn’t he care? Why wasn’t Van Zanten focused on knowing, with certainty before commencing takeoff, that Pan Am was not on his runway?

Armchair accident enthusiasts seem to be divided into two camps regarding Van Zanten, neither of them lenient. One viewpoint is that the 50-year old KLM captain acted in an arrogant and impatient manner the afternoon of the crash, adopting a tone of annoyance and sarcasm. His attitude essentially shut down the valid concerns of his crew, concerns that if more assertively voiced could have transformed a low speed aborted takeoff roll into a non-event.

A harsher assessment of Van Zanten is that he took off with a blatant disregard for the possibility of another jet in the heavy fog occupying his runway. That he was a bully, eventually intimidating his subordinates into silent compliance. A pilot so domineering that he would wait for no one, even if it imperiled his life and his passengers. Not that Van Zanten had a death wish per se, but that he recklessly took the lives of the almost 600 who died in the accident. Well, if you could call it an accident. In the eyes of some, it was practically intentional.

But is that tarnished image the true Captain Jacob Van Zanten? For ten years prior to Tenerife, the husband and father to two children was a training pilot and simulator examiner for KLM. Eventually promoted to Chief Pilot for all of KLM, and put in charge of the B747 training program. The very person belted in next to him during the crash, copilot Klass Meurs, had just been signed off as a new copilot only two months earlier, with Van Zanten administering the checkride.

Having been an airline check airman, I’m aware that one of the many advantages of the position is that you become very current on the maneuvers, emergencies, and general handling of the airplane when you spend day-in and day-out in a full-motion simulator. The downside? Realistic as it is, it’s still not the real world. Van Zanten had spent years in the simulator, and the KLM offices, far away from the realities of line-flying.

Adding to the pressure was his management title and position as de facto training authority for the entire company making the expectations on him even greater than for a regular line pilot. When the bomb blast shut down his destination airport, he was quickly barraged by a panorama of problems and irregularities he wasn’t accustomed to. Line pilots contended often with alternate airports, and weather closing in, and company flight time duty limitations and other factors that affect not only their decisions, but even their mood, and modus operandi.

In some respects, for all his accolades, Van Zanten was a bit rusty out in the real world. And what’s the one voice you never hear in the simulator? Air traffic control.

We’ll never know for sure why his co-pilot or flight engineer didn’t yank the four throttles to idle and prevent Van Zanten’s takeoff roll. Was it, as has been speculated, intimidation? Or was it their hopeful belief that as the captain, as the final authority, he must be right. With such high life and death consequences – and their own unsettled words regarding Pan Am’s location – it is startling that the crew’s own self-preservation instinct didn’t kick in and make them act.

Jan Bartelski, a KLM captain and president of the International Federation of Air Line Pilots’ Associations, described Van Zanten as open-hearted, with a friendly disposition, a man who believed in partnership in the cockpit. “He insisted his first officers address him during flight as ‘Jaap’, the Dutch nickname for Jacob, and not as Captain,” said Bartelski.

Have I ever personally had to stop a captain from taking off? Once. On a parallel runway that was closed, and in the distant invisible dark, cluttered with trucks and construction equipment. But it was an easy call, we weren’t under any of the extenuating circumstances of Tenerife. The consequences? None. And some good came of it, as the close call got the captain to start paying more attention and get his head back in the game of flying, which had been noticeably absent over previous weeks.

Some may always believe that instead of an honest mistake, Van Zanten’s error was the careless arrogance of a pride-filled poster boy. Sometimes the collective takes comfort in easy blame, maybe because somehow it translates into less chance of it happening to them. We’re the pilots raised on crew resource management, the breed that listens. And solicits and accepts input from crewmembers. Even the ones we don’t like. But, every day, every flight? Safe in the bubble atmosphere of team mentality, could we never lapse, at precisely the wrong moment, toppling our own last domino in a sequence that becomes visible to our experienced eyes only in the final helpless seconds?

There would be no reason to suggest Van Zanten believed anything else than his runway was clear, and he was cleared for takeoff. There’s absolutely nothing to suggest he was suicidal or homicidal. He thought he was good to go. An inescapable irony lingers that in trying to remain under duty time, in getting distracted by the schedule, and of avoiding extra expense for the company and inconvenience for his passengers – in trying to be a good employee – he became, momentarily, a very bad pilot.

The Legacy of the Tenerife Airport Disaster

At the time of Tenerife, the Boeing 747 was invented only eight years earlier. Now in the era of more efficient twin-engine jets, the iconic ‘double-deckers’ are being repurposed as cargo queens, to make room for newer and bigger passenger capacity jets like the Airbus A380.

With that increase in size comes an inherent potential for large fatalities in even a single aircraft accident. Most A380’s are configured to carry around 550 passengers, but the jet is certified to carry up to a whopping 853. Imagine two of them in a collision and do the math.

The good news is that the airlines have not yet surpassed the human death toll at Tenerife of 583 lives in a single accident. The concern is that we keep having close calls. The FAA and ICAO have worked to promote effective runway incursion programs to reduce the chance of aircraft ground collisions. But the Wall Street Journal reported last year that hazardous runway incursions in the U.S. increased three years in a row, jumping 25% in 2016.1

It’s also an issue overseas. On October 10, 2016, China Eastern Airlines flight MU5643, an Airbus A320, was involved in a serious runway incursion incident during takeoff from Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport. As the A320 accelerated for takeoff, an Airbus A330 wandered across his runway. The China Eastern captain, accelerating through 110 knots, spotted the incursion ahead, hit TOGA thrust and rotated at 130 knots, climbing over the A330, missing it by only 60 feet.

In the end, call it fate, or call it luck, but fortune remains the unseen element X of the accident equation. If you don’t believe luck swirls around airline tragedies, then maybe you haven’t heard of E. Jack Ridout.2 He was one of only 61 survivors at Tenerife, all from the Pan Am jet. That alone was an unbelievable stroke of good fortune, more than most could hope for in a lifetime.

But one year later, in 1978, another deadly airline collision occurred, and Ridout had a ticket on that flight too. It was Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 182. The PSA Boeing 727 was hit by a small Cessna airplane over the clear skies of San Diego, killing a total of 144 people. One of the most eerie photos in aviation history shows the sunny silhouette of the Boeing tri-jet, falling from the sky, seconds before impact.

Ridout survived the crash of PSA182 because he decided to skip the flight. What are the odds? On March 27, 1977, it was to some intangible degree, bad luck that conspired with so many other factors, including his own bad decisions, to prompt Captain Van Zanten to take off into the blind without clearance. Jack was incalculably lucky. Jacob was not.

Final Thoughts

Have I ever witnessed a fully loaded passenger jet takeoff without clearance? Yes. And like Tenerife, it was at a tropical tourist destination airport. I was 29 years old, in a hurry, and at the controls. Did anything come of it, beyond a gentle scolding from the tower? No.

That’s how I know there’s another Jacob Van Zanten out there, somewhere. I’ve flown with him. And at one time or another, I may have been him. Even as we try so hard to focus on doing the right thing, on getting the job done. There’s a bit of Van Zanten lurking in every pilot. It manifests in its deadliest form as a blind spot to our own human mistakes, to our own bad luck moments, especially the sneaky ones of our own creation.

Featured Image: courtesy of Pieter Van Marion, CC BY-NC 2.0 (Editorial Note: While this is a photo of a KLM Boeing 747, it is not a photo of the actual aircraft that was involved in the Tenerife Airport Disaster.)

References:

1 – Close Calls on U.S. Airport Runways Rise Sharply, Wall Street Journal, Andy Pasztor, Retrieved 3-29-17

2 – A TWIST OF FATE: ‘I’ve Been Called a Survivor for Years’, LA Times, Mike Granberry, Retrieved 3-29-17

Pilot Persuasion: Effective Crew Resource Management

To err is human; to crash, unacceptable. If we know that humans inevitably make mistakes, how do we balance that idea and still keep airplanes safely in the air? While new technology and computer are great at pulling in and regurgitating input, their interpretations can be just as fallible as a pilot’s. All airline pilots have heard about Crew Resource Management (CRM). Sure, they’re given the definition, and they understand the philosophy, but to truly understand its hidden power, pilots must use the concept of [Click to read more…]

To err is human; to crash, unacceptable. If we know that humans inevitably make mistakes, how do we balance that idea and still keep airplanes safely in the air? While new technology and computer are great at pulling in and regurgitating input, their interpretations can be just as fallible as a pilot’s. All airline pilots have heard about Crew Resource Management (CRM). Sure, they’re given the definition, and they understand the philosophy, but to truly understand its hidden power, pilots must use the concept of [Click to read more…]

What a great article Kathleen…I can see why you’re an award winner. I really like how you blended the accident with CRM which doesn’t allow US(pilots) off the hook–“I would never have done that!”

Great Line…Safe in the bubble atmosphere of team mentality, could we never lapse, at precisely the wrong moment, toppling our own last domino in a sequence that becomes visible to our experienced eyes only in the final helpless seconds?

I’m going to put a copy of that on my briefing card. With 23,000 hours I’m still learning that sometimes I’m the biggest threat/hazard in the cockpit.

My wife constantly reminds me I’m the biggest hazard at home.

Thanks for writing a great article. Hope you get some well deserved appreciative feedback.

Cheers!!

I was a young teen in the 8th grade when this horrific accident occurred. It troubled me greatly. As a very young boy in the mid-60s’ I had flown commercially (Eastern & Delta) with my mother, from NC to visit relatives in CA. On our last visit we also flew cross-country to visit additional extended family members, from San Diego to Tuscon and then back to SD in my cousin’s Mooney…(he was an ATC guy as a career). Even at such a young age, I could fathom the risk and also the wonder and excitement of ‘flying’. Fast forward my life 50+ years, and now I am a retired A&P and pursuing (FINALLY!), my own ‘Private Pilot Rating’.

While stationed with the US Army in Cold War West Germany in the early 80s’, one of my best friend’s dad, one of my best friends, and a 12 year old boy all perished back here in the US in a well weathered C172…due to…”fuel exhaustion/ controlled flight into terrain”, i.e.. a telephone pole and wires array. I had flown many times before with the owner and his son (not one of the victims) in this same plane. He would often push the limits for thrills, etc., to please and entertain us. I knew something was just not right but, I was only 17 years old, and “trusted him”, as the PIC that knew exactly what he was doing.

Last summer while training for my own ‘ticket’ I had to transition to an alt. CFI, (mine suddenly resigned from the flight school), and on our first take off together, the aircraft all but completely departed the runway (to the left), as I almost broke my foot, ‘standing’ on the right pedal! Also note, I had apparently not “slapped the throttle to the firewall” rapidly enough to suite the new CFI, so he did it for me! Without warning! Suffice to say “together”, we got the craft stopped and off the runway…but boy was he pissed at me and convinced I had never stepped on the right pedal. I was so scared and embarrassed, I could only clam up and could hardly speak! He took it back around to the numbers again & took a turn…same thing…sudden swerve the left no matter how much right rudder input. Turns out…(since he was a quite tall fellow), that he had inadvertently, adjusted ‘his pedals’ too far forward, which caused them to limit the distance available for travel to the right side…the right pedal jammed on the ‘firewall/cockpit’ before full deflection could be achieved. “Why did he not know about this fluke of design?” The plane here was a well used DA20. Also note that we too had cascading events leading up to this near catastrophe, prior to taxi for departure…the plane was late to be delivered from other airport to us…he also ‘killed’ the battery trying to hot start the craft when we finally got in it…he never even asked or considered that I could start the craft just fine! After all, I was a retired A&P with over 30+ years experience in ‘starting’ (under many conditions), numerous ‘types’ from B727s’, biz jets, turboprops, and too many common GA prop aircraft to list here! THEN, after 1 more lesson…I had to delay my training for a bit due to some questions that came out of nowhere from the FAA regarding a few fine and a bit silly points about my Class III medical. Thank God for the pending MED reforms set to become law next month. Thank God this is the United States, where freedom and choice are the laws of the land, and yes…there ARE more ‘Captain Zantens’ out there both seen and unseen, known and unknown, for better or worse. I am currently seeking a new school, CFI cadre and aircraft type, to train in. With only 17 hrs total so far…I still have a long way to go. Thank you Ms. Bangs for the excellent recap and prudent reminder of just how far-south, an authority figure under stress and pressure to ‘perform’ can take him/herself…and take ‘innocents’ all the way down with them. Safe flights and Godspeed to all who venture into the ‘realm’.

The most insightful study on the whole incident [40 years later to get any closer to what is was is still difficult]. One thing I must confess, that makes me grin…

I thought this article was written by a man! I didn’t read who wrote it until the very end! So, at age 58 and considering myself to be as broad minded as the next guy, I immediately assume an article written about Tenerife is written by a man.

Oh, the more things change…

Cheers,

Jonno

To make it simple and without want to be disrespectful, “shit happens” because we are humans.

When pilots are in the limit of their duty time the brain works slower, you are in your alternate, there is fog, is difficult to refuel (the article doesn’t go deeper in how was the refuel sequence with airplanes parked on the taxiway), and as Captain is your work is to try to complete the flight in a safe way and following regulations, etc…very easy to judge the KLM crew from a computer, basically a one second mistake between understand if he was clear for take off or not was the only deviation from procedures the Captain made,

he thought he was cleared he didn’t deviate in purpose from a procedure: this was a mistake, not a violation.

And not fate or luck avoided the accident in China mentioned in this article they were with Flex take off thrust and the Captain hit TOGA thrust and pull to avoid the crash, both airplanes were cleared to cross and take off by a mistake of the controllers, not pilots mistake in this case, we are humans mistakes happens…

I took off by mistake once without clearance due a confusion on the phraseology and both were speaking the same language…

In fairness to the PSA accident, I would say that the Cessna didn’t hit the 727, so much as the 727 hit the Cessna per the NTSB report and collision angles-

“Now in the era of more efficient twin-engine jets, the iconic ‘double-deckers’ are being repurposed as cargo queens, to make room for newer and bigger passenger capacity jets like the Airbus A380.”

This sentence makes no sense, on a number of fronts. One, the A380 isn’t selling anymore. Two, we are definitely in an era of more efficient twin-engine jets, so more airlines are moving away from the 747 for the 777, 787, A350.

Now, this was a well-written, thorough reflection, but it’s hard to imagine why the section about the legacy of Tenerife begins with this contradictory statement.

The high passenger load Airbus A380 is still being manufactured.

The reference to ‘iconic double deckers’ means the Boeing 747.

The article is stating that passenger fleets have moved away from less fuel efficient 4-engine aircraft, and into 2-engine jets.

Great article Kathleen, especially the events leading up to the incident which allowed the swiss cheese holes to line up. It does also make you wonder if Van Zanten was suffering from confirmation bias which caused him to disregard information to the contrary. In his mind Pan Am was not on the runway and he was cleared for takeoff. No doubt the stressful environment he was working under contributed to that, including the mission-oriented pilot mentality you alluded to.

I did read your article with a lot of interest. I do live in the Netherlands, and English is not my mother language. A couple of days ago, I did see something about this disaster at youtube and do see many reactions. And now, I did find your article and the way you did write it, is I think the way to write about accidents. But still some remarks, if you do not mind.

draconian penalties

In the Netherlands, we call them safety laws. Many accidents do happen because people get tired. We have a good climate for employees in The Netherlands, so employees do get protected against employers. Perhaps a chock for people who live in US that in the Netherlands employees are protected 😉

But there was no problem, at least not for the crew, they were protected. In fact, in the cockpit Van Zanten contacted KLM HQ to tell them that perhaps they would not make it in time. So KLM, be ready to arrange everything. Very clever of course to inform employer. But that was it. KLM HQ said that they thought he would make it on time, but if not, they were ready.

Besides, PanAm kept passengers on board, KLM let passengers of board, arranged special boarding passes, buses, to let people do shopping in tax-free shops. And yes, when they returned, a couple of passengers were missing, so let’s wait more time (youngsters of course, but parents wanted to have them on board as well).

But well done US investigators and Spanish investigators to tell the world we have a cruel country protecting employees. Oh no wait, they did not tell last part, just imagine that employees in US also want to become protected.

It is a complete farce, co-pilot and pilot were talking about not to takeoff when they were on the runway. They thought there would be problems with weather. Co-pilot: but then we will block runway. Pilot. there is an exit, we will take that one. Why do people not read official CVR’s?

Most interesting, there are CVR’s on interne, but weird ones. First as if we are sitting in cockpit PanAm (everything nice, everything cool) and then in KLM cockpit …. Weird. But I think you can find the offical ones as I did.

So was Van Zanten keep things moving? Yes, he moved passengers out of plane, put them in buses, and let them have fun in tax-free shops.

A true nightmare for Van Zanten, absolutely, he had to wait till youngsters came back to plane, parents were worried, a nightmare for Van Zanten.

But do US investigators and Spanish investigators write about it. NO WAY.

perhaps you have heard that one young woman stayed in tax-free shop, she said goodbye everyone, I go to boyfriend, skip a nice evening party of her employer. The woman’s name is Robina van Landschot. They were all of the plane, het planned sister in law returned to airplane ….

Next remark, it is correct but why go to end runway and make 180? C-4 was open, C-5 was open that was the easiest way for a 747. When Van Zanten did see C-4, he asked co-pilot do we have to go of here? Co-pilot said no, end runway. And then make a nice turn with this jet. Van Zanten must have thought, they are nuts.

Jet yes, the controllers were Air Force people and I think they had the greatest fun to tell a 747 to go to end runway. And tell PanAm to take exit-3. C-3 is a 148 turn, followed by another one. PanAm pilot must have thought, they are nuts.

I think that someone who would have tried to avoid accidents would never acted as this tower.

Option 1 – Let PanAm wait, in fact pilot PanAm wanted to wait, read CVR Panam.

Option 2 – Let KLM take C4, let PanAm go to end runway, make a 180, and take off, followed by KLM.

Option 3 – Let KLM and PanAm take C-4, and when PanAm has taken C-4, let KlM go to runway.

In all these options, the runway is used as taxiway (one or more planes) and runway (one plane). I’m not an expert, but are these options weird? In chemistry we do take precautions. When I would have worked like those people in tower, I would already been dead for years.

Tower choose option 4. And watched a football game.

Sorry, but I think the people in the tower had greatest fun to see those 747’s moving over their airfield. OK, there was a problem, there was fog.

Do you know that KLM first did get the order to take exit-3? This was recalled. That would have been too much of course, 2 747’s doing 148 turns … Air Force people giving orders to 747’s as if they were jets.

And the ground controller did take time to learn the PanAm pilots to count, 1, 2, 3, yes, 1, 2, 3. (One of the PanAm pilot counted 1, 2 , (four), apparently they were not sure about it, but it did not sound like three.

But no, there was nothing wrong with their way of acting, order is order. Unbelievable.

If people like them would act on my floor, they are fired at once. Safety first, complete neglect of safety by tower. Everyone has to avoid in accident. They had to choose option 1, option 2 or option 3, or close airport.

They choose option 4, and everyone does say order is order. Investigators do say order is order, completely nuts. Do those people take care of our safety?

In fact, I read a lot now, and sorry, those investigators I do not want on my floor. I do not want amateurs. Have they never heard of blanks? What happened with the other airplanes? Get their blackboxes as well and see what happened that day. But cost too much money of course.

But call it investigations? No way.

I read somewhere that 3 planes left before and were ordered to take ….. C-4. So the tower did know there was a C-4. Why tell 747’s to take exit-3?

Van Zanten told tower he was at C-4 …. Tower said ok, so they did know they had a C-4….

Next remark: “Van Zanten mistakenly takes the clearance as a signal that he is cleared for takeoff, and again applies power. The Pan Am crew recognizes something is amiss and nervously broadcasts that they are still on the runway.”

Yes sounds acceptable, bit perhaps a bit more?

1706:20.3

RD0-2 And (*) we’re still taxiing down

the runway the clipper one seven

three six ((1706:23.6))

1706:25.6

APP Roger pappa alpha one seven three

six report the runway clear

((1706:23.9))

1706:29.6

RDO-2 Okay we’ll report when we’re

clear ((1706:30.9))

1706:32.1

Let’s get the (*

##) right here

get the « # out

of here ((chuckle))

((1706:34.6))

1706:34.9

CAM-2 Yeh, he’s anxious isn’t he

1706:36.2 •

CAM-3 Yeh after he held*’us up for

an hour and a half, that

##

1706:38.4

CAM-2 Yeh, that #

1706:39.8

CAM-3 Now he’s in a rush

1706:40.6

CAM-1 There he is look

at him ###

that that ###

###’•*-‘* is coming

(‘(1706:45.6))

1706:45.9

CAM-2 Get off! Get off!

Get off! ((1706:47.9))

1706:48.7

CAM ((Sound of takeoff warning

horn))((Sound of approaching

KLM engines))

Let’s get the ##) right here get the « # out of here ((chuckle)) … KLM was just given an ATC clearance.

Yeh, he’s anxious isn’t he … KLM was just given an ATC clearance.

Yeh after he held*’us up foran hour and a half, that ## … KLM was just given an ATC clearance.

Yeh, that # … KLM was just given an ATC clearance.

Now he’s in a rush … KLM was just given an ATC clearance.

And then … There he is look at him

I think that PanAm pilots also were a bit worried. In those days clearances were not so clear, FAA did write document before accident about clearances …

It was not unusual to do it does way in those days, procedures were changed.

How can the PanAm pilots be worried when it is just an ATC clearance?

The tower ordered KLM to go to end runway, make a 180 and report for ATC clearance.

Why were the PanAm pilots worried? Did they also hear a possible takeoff clearance? Please, in those days they worked a bit different.

Next remark: KLM technician

What you state is wrong, it was not at that moment, but seconds later.

He heard:

1706:25.6

APP Roger pappa alpha one seven three

six report the runway clear

((1706:23.9))

1706:29.6

RDO-2 Okay we’ll report when we’re

clear ((1706:30.9))

But the call was weird, there was no Clipper in calls. Then he asks:

1706:32.42

C? (was it the technician?) Is he not clear then? (Is he not there off)

1706:34.10

C1 What did you say?

1706:34.7

C? Is het not clear that Pan American (Is he there not off

that Pan American)

((1706:35.93))

C1 1706:35.70 Oh yes (well yes) ((1706:35.99))

They were already taking off, but yeah 13-15 seconds

Bujt you state explicitly highly-experienced crewmember, ok fine, that does mean

even the highly-experienced crewmember was uncertain. Just like the PanAm pilots,

but all 4 did do nothing.

The very person belted in next to him during the crash, copilot Klass Meurs, had just been signed off as a new copilot only two months earlier, with Van Zanten administering the checkride.

On a 747 ….

In some respects, for all his accolades, Van Zanten was a bit rusty out in the real world. And what’s the one voice you never hear in the simulator? Air traffic control.

PanAm pilots as well? Very clear they heard a possible takeoff in it as well.

“We’ll never know for sure why his co-pilot or flight engineer didn’t yank the four throttles to idle and prevent Van Zanten’s takeoff roll. Was it, as has been speculated, intimidation? Or was it their hopeful belief that as the captain, as the final authority, he must be right. With such high life and death consequences – and their own unsettled words regarding Pan Am’s location – it is startling that the crew’s own self-preservation instinct didn’t kick in and make them act.”

Why did the PanAm pilots not call mayday mayday?

“An inescapable irony lingers that in trying to remain under duty time, in getting distracted by the schedule, and of avoiding extra expense for the company and inconvenience for his passengers – in trying to be a good employee – he became, momentarily, a very bad pilot.”

An inescapable irony lingers that people in US still believe this bullshit. Hello, he lived in the Netherlands, not in USA, Netherlands was seen as most tolerable country in those years. Everyone knows, but for this accident people forget?

The PanAm pilot was stressed as a chicken. Read CVR.I would be nervos as well, 1,2,3, yes, 1,2,3, 1,2 (four).

“Kathleen Bangs is an on-air aviation analyst, former commercial airline pilot, and 2005 overall winner of the International Aerospace Journalist of the Year Award. She has over 10,000 flight hours, and a fondness for the Reverse Cuban 8.”

In 2 days I got more than you.