One private pilot’s experience with finding out about the mountain wave the hard way.

It was a lazy, sunny southern California Saturday in February 1998. We didn’t yet know it, but we were almost going to die that day. I sat in the kitchen reading the paper as the morning’s quiet was interrupted by the ringing telephone. It was my son calling from Mammoth Mountain, where he had been on a ski trip. A storm was predicted for the next day and they had decided to leave early. He would be home in eight hours. “I wish I was flying; then it would only be an hour,” he grumbled. Back then, with cheap fuel1, who wouldn’t jump at an excuse to go flying? A call to weather confirmed clear-as-a-bell conditions and light winds so a deal was struck for us to fly up in our Cessna 210 and meet the car with my son at noon at Lone Pine Airport, a one-hour drive down from Mammoth, in the Owens Valley, just east of the Sierra Nevada.

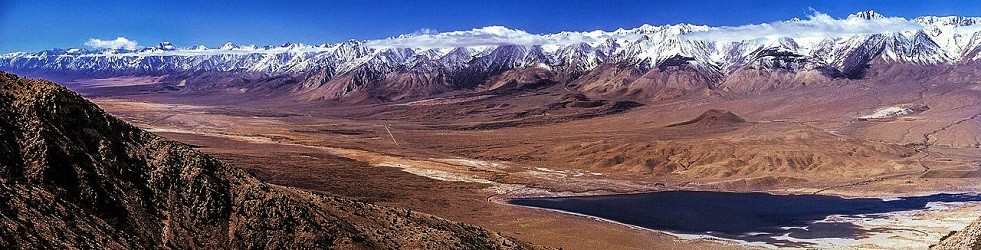

We had bought our airplane just 10 months previously. I didn’t have my certificate yet but had already flown all over the United States with my husband and our three kids, ages 10, 9, and 6. We typically traded off flying duties. On this day Fred was in the left seat; the other two kids were in back. From Santa Monica, we flew GPS direct, which took us over the mountains at 13,500 feet with Mount Whitney abeam our left and the snowy tops of other peaks a mere 500 feet below us. The view was breathtaking, the air cold, clear, and smooth. Our true airspeed was just under 160 knots and the GPS-indicated ground speed stood at 175. The tailwind was as predicted, about 15 knots.

Getting Hit With a Mountain Wave

We approached the eastern edge of the mountains, where the terrain drops almost straight down to the Owens Valley. This is one of the steepest and deepest drop-offs in the continental U.S. Just as we approached the edge the GPS showed our groundspeed increase rapidly from 175 to 228 knots. A moment later the plane crossed the ridge and suddenly everything went wild. The first smack knocked our headphones off and our heads into the ceiling despite seat belts. The kids in back screamed; they had secretly unbuckled their belts and were being tossed about. If you can imagine floating calmly in the ocean and suddenly being sucked over the edge of a 20-foot wave, you have the idea. There was no turning back; the wind was simply too strong.

Fred cut the power to idle in an attempt to keep the airspeed down. The winds swirled wildly around us. Fred was essentially flying as you would ride a bucking bronco, trying to go with the movements of the wind so as not to overstress the airframe. The airspeed indicator moved violently from close to VNE to stall and back and he compensated with full or no power, more or less elevator, and standing on one or the other rudder pedal. He said later he fully expected us to roll. I stayed quiet so as not to distract him; thankfully the kids had somehow managed to get back in their seats and buckle in. It was impossible to find any headsets and I closed my mouth so as not to bite my tongue off when we would get slammed up, down, or sideways.

Frequently the airplane was uncontrollable. We were caught in a violent rotor on the lee side of the mountain, something I hadn’t read about yet. Our gyrations eventually sent us a bit farther east, away from the mountains, and then the waves began. The vertical speed indicator was pegged, but a digital multi-function instrument on the copilot’s side told the story.

An insane 7,300 fpm down with full power in would end in a violent jolt where I really thought the wings would break off. This was followed by 8,200 fpm up and idle power, the updraft ending violently as our heads slammed into the ceiling. Then we dropped and I saw 5,700 fpm down. Several times I looked out my window and down at the ground far below. In my mind’s eye I saw the fuselage of our red airplane, wings stripped off, rotating as it went down, and then a “poof” at the bottom, sort of like the coyote on a roadrunner cartoon, when he hits the bottom after going off a cliff. But this wasn’t funny. We all feared we would die.

This went on for perhaps eight minutes, and slowly the rotor and mountain wave pushed us over the center of the valley. As we were able to lose some net altitude, I perceived a slight improvement in our condition. We would live! But how to land in this? I needn’t have worried. By the time we got to the airport, the wind was completely calm.

We stepped out. I had never before literally experienced being “weak in the knees” but I was now, absolutely wobbly. The air at Lone Pine Airport was completely still—warm air that felt like velvet when you breathed. A few minutes later, the car with my son in it pulled up.

“How was the flight?”

“Oh, just fine,” we said with weak smiles as we gathered the boy’s things, not wanting to alarm him.

Obviously, we weren’t flying back the same way that we came. Since it was so calm down low, we decided to follow U.S. 395 south out of the valley. Incredibly, the other two kids got right back into the airplane with us (such is the trust of a child) and we set off, staying low over the desert valley just east of the highway. A few miles south of the airport, we were suddenly hit with an enormous blast of wind from the side, coming down the lee of the mountains. With each second the velocity increased, so we peeled off to the left for a quick one-eighty. So much for that plan.

“Let’s try to climb out to the north instead,” I suggested. But by the time we reached 9,000 feet the turbulence had increased again. It was time to quit. We landed, walked into town, and got a pair of motel rooms. Then it was time for a pizza to celebrate not being smashed to pieces.

When we emerged from the restaurant I turned and saw the biggest lenticular cloud I have ever seen, right over the area where we had experienced the extreme turbulence and mountain wave. It hadn’t been there before, but moisture was coming in just ahead of the cold front that would bring snow the next day by noon. That night my husband called flight service. Winds at 12,000 feet were 72 knots!

The Morning After Encountering the Mountain Wave

The following morning we were in the air at sunrise, again staying low and following the highway south. The wind was much calmer, but we still got a few bumps before we finally got the heck out of that valley. After we got home we had our mechanic check the wing spars and other stress points; the plane was OK.

I ramped up my reading after that. What did I learn? Always check the winds aloft when flying in mountains. Mountain wave conditions can exist whenever the winds at ridge level are greater than 25 knots. In our case the briefer reported 15 knots but that was nearly two hours before we crossed that ridge; this was way before satellite weather was available in the cockpit. The smooth ride up to that point had given us no reason to call FlightWatch enroute.

Clearly, however, winds had increased markedly by the time we arrived in the area. And if the air is dry, the tell-tale lenticular clouds won’t be there, but the turbulence will. Also, check the barometric pressure. If there is a large difference from one side of a mountain another—wind flows from high pressure to low—you will likely get bumped on the lee side. Allow at least 2,000 feet between you and the mountain to avoid a rotor. We were too close to the rocks. And watch approaching cold fronts in winter with cold, stable air. This creates a situation where the cold air is just pushed over the mountains like water. Besides the possible rotor, the mountain wave action set up in these events can continue up to a couple of hundred miles downwind of the ridge. Fly at a 45-degree angle as you approach a ridge, so you can turn back more easily. In our case, however, we had only a few seconds’ warning.

I still fight fear whenever I feel bumps in conditions that could theoretically lead to even moderate turbulence around mountains. Here in Idaho, if winds are above 20 knots we stay away from the mountains. Flying can wait until another day. The Owens Valley, in the lee of the Sierra Nevada, and Boulder, Colorado, in the lee of the Rockies, are two spots that harbor the most extreme mountain wave turbulence. Another notorious area is in the mountains between Taos, NM and Colorado Springs, CO. We now give any mountain plenty of room.

Footnotes:

1 – AvGas was roughly a dollar a gallon in 1998, according to historical data.

Great article. I’ve always believed that a checkout to Mammoth should be available for SoCal pilots after getting their ticket. I think that many of us have lived this article and learned the hard way.

I flew down there just last weekend and encountered some serious turbulence. Sometimes it seems like the more beautiful the area, the more deadly.

Wow! This was gripping and harrowing intertwined with important technical details. I’m so glad you and your family are okay. Phew.

Long story short a couple days an Alaska Airlines pilot gave passengers a tour of Mt. Rainier because fog prevented him from landing at SeaTac. In the comments of the news article someone mentioned mountain wave turbulence. I had never heard of it before so I set out to do some research and came across this post. I’m glad I did because it went well beyond graphs. You gave a personal account of what can happen, albeit terrifying. Thank you for sharing.