Aviation History Is Full Of Great Stories and Important Lessons

If you don’t know where we’ve been you won’t know where you’re going.

Today’s aviation press is full of news about the Boeing 787. The 757 and 767 and 737 are now the workhorse standards in the airlines. Once considered immense, the 747 and its oil-burner cousin, the 727 has been relegated to set on the shelf next to Beatles 45s and vinyl disco albums. But what was it like when the print press reported, “The DC-3 is now almost standard on all major airlines.” Or “You can crawl into a comfortable berth ten-thousand feet above the Arizona mountains, fall asleep to the low roar of engines and wake up with the nation’s capital glistening far beneath you in early morning sunlight.” No, my little EFIS and GPS friends, you won’t read those words in 2016. These are part of aviation history and are the 1941 words of author Ernest Gann in his book All American Aircraft. Why Mr. Gann even promises at 196 miles per hour, you can go from LA to NY in only 12 hours!

As I sit in this creaky old library with its equally-creaky prune-faced librarian’s disapproving glances at my flip-flops, I hear an Airbus passing overhead, aligning itself on the approach in the AUTOLAND mode.

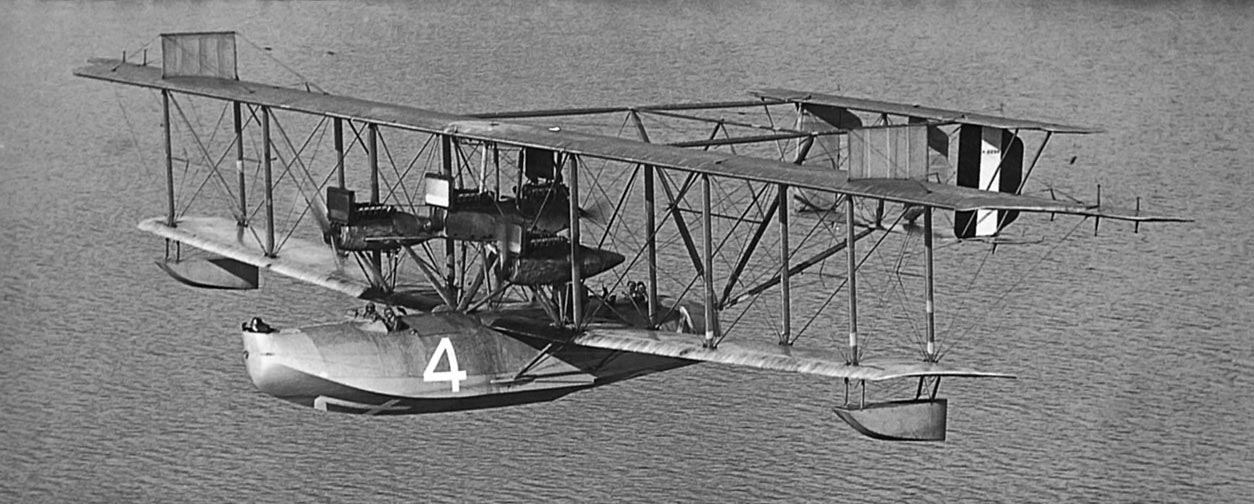

What about this book here … Spirit of St. Louis? Author and famed aviator Charles Lindbergh predicts that transoceanic flights will be commonplace one day with the help of amphibious aircraft and floating ocean fuel stops! Impossible!

Meanwhile, a bloated Madrid-bound Boeing 767 lifts off the crossing runway nearby with 24,000 gallons of fuel in its tanks; that’s 162,000 pounds, which is equivalent to a fully-loaded Boeing 737-700 with two Cessna 172s stashed in its baggage compartment.

We get hypnotized and de-sensitized every day by all the gee-whiz stuff we see coming down in aviation. A well-rounded pilot who knows about aviation’s roots and explores aviation history will understand and appreciate better that which exists today. For me, the best place to find that on this rainy afternoon is at the local library. The coolest books are the ones that are most beat up. They’re the books that have got the juicy stuff you don’t see written anymore.

Let me illustrate what I discovered this afternoon. Try to match the items in the first list with the items in the second list below. Had I not been thumbing through old books that smelled of old-ness, I would not have been able to match them correctly myself.

- Piloted the first airplane to cross the Atlantic

- Pilot who helped invent artificial heart

- Wrote articles for “Cosmo” (“Cosmopolitan”) magazine

- First recorded bird strike by an aircraft

- Invented the safest mode of travel

- Only airplane to ever be on the moon’s surface

- Pilot as well as a licensed ham radio operator

- A. Amelia Earhart

- B. Charles Lindbergh

- C. Elisha Otis

- D. Jeana Yeager

- E. John Alcock and Arthur Brown

- F. Orville Wright

- G. Wright Brothers “Wright Flyer”

Here are the answers to these aviation history questions: 1-E, 2-B, 3-A, 4-F, 5-C, 6-G and 7-D. How’d you do?

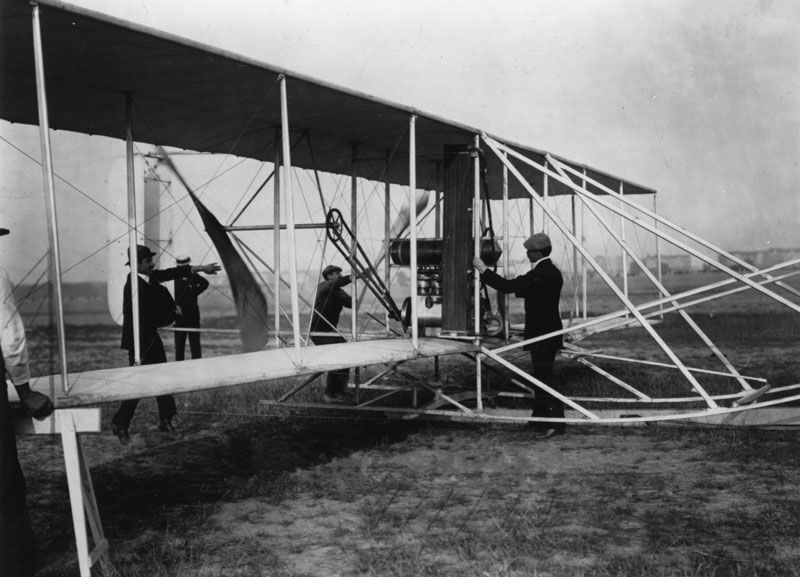

By the way, perhaps I included a little bit of a trick although I did it because it’s an interesting fact. The safest mode of transportation is actually considered to be the elevator which was invented by Elisha Otis. Flying is the second safest mode as determined by safety experts. And…no kidding… astronaut Neil Armstrong carried a piece of the Wright Brothers original airplane (the “Wright Flyer”) when he walked on the moon in 1969. The “Flyer” crashed after its first 4 flights on December 17, 1903, was badly damaged and never flew again. It has been restored and is on display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

We take for granted our approach charts and electronic flight bags (EFBs). Anyone who has ever opened the pages of the TERPS Manual will agree that you must have to be a guru of detail and trigonometry to create those profiles that we fly so routinely. But in 1930, there were no instrument approaches. In those post-depression years, United Airlines Captain Elrey Jeppesen started keeping a little black book in which he drew diagrams of the airports and the obstructions surrounding them. On days off he would climb to the tops of mountains on foot with a barometer to measure their height, denoting it on his drawings.1 Soon other airline pilots asked Captain Jeppesen for copies of his book and the aviation charts as we know them were born. We owe a lot to him.

The original Mercury astronauts are icons of aviation history. Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, John Glenn, Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra, Gordon Cooper and Deke Slayton all deserve every pilot’s admiration and respect. They were true trailblazers. But each one had quirks, skeletons in his closet and personality traits that made them fascinating…and human. Alan Shepard’s biography, Light this Candle paints a salty picture of all of them. The joint writing of Moon Shot by Shepard and Deke Slayton illustrates that competition between pilots became political, mean-spirited and petty. As an off-the-rack truly unspectacular pilot myself, it is fascinating to learn that these bigger-than-life heroes were just “regular guys.” Their weaknesses, fears, hopes, failures and humanness reveals that none of us are really any different.

It’s easy to become desensitized to technology today. Until you blow the moldy dust off of an old aviation history book that explains first generation systems used by pilots, you probably don’t realize how far we’ve come. When is the last time you had to worry about mandatory reports to ATC when not in radar contact? Yep. It’s still in the regs. But rarely, if ever, must we use them.

I did not get a real sense of how far we’ve come until discovering the books Adventures of a Yellowbird by Robert Mudge and The Triumph of Instrument Flight by Franklyn Dailey:

“Each airline flight was conducted on the assumption that the flight would not be routine – that emergencies might take place. Accordingly, each foreseeable and conceivable emergency had a carefully prescribed and programmed antidote.”

Consider for a moment if ground and inflight engine fires, smoke in the cabin and radio failures were so commonplace that they were integrated into normal checklists and expected on each flight. Such things were expected during those carefree days in the aviation routine of Mudge and Dailey.

There are old books that are a part of aviation history and are as timeless and as pertinent today as they were when first published. One is an excellent book on aerodynamics and every flight instructor should own it: Aerodynamics for Naval Aviators by Hugh Hurt Jr. Since published in 1960, it has continually been in print and now offered by the US government printing office as well as many private publishers. It’s THAT good.

I think just about every beginning pilot is coerced into buying and must endure praises for Wolfgang Langewiesche’s 1944 book, Stick and Rudder. This book is interesting, not because it is considered a standard but because it is a little strange. For instance, the late Mr. Langewiesche says this about rudder use:

“The important thing to understand about the rudder pedals is that they are unnecessary; like your wisdom teeth, they serve no very good purpose but can cause much trouble. The airplane needs no rudder pedals. It should have no rudder pedals. In all probability, it will have no rudder pedals 10 years hence.”

I don’t know how he did his cross-wind landings but speaking for only me, I LOVE MY RUDDER PEDALS. His thickly opined treatise is fun to read if you take some of it with a grain of salt. Another famous quote from his pen is, “He who flinches or hesitates is lost.” While this might be true in the final seconds of an eBay auction it throws ice-cold water in the face of good decision making and cockpit resource management.

Pick up any World War II era book on flying and you will quickly realize how incredibly far we’ve come. Not only in the advances in aircraft design, performance and efficiency but aerodynamics and plain old garden-variety instrument flying. Today’s instrument pilot is guided through approaches with flight directors that tell the pilot which way and how much to correct for course and wind and also take the guess work out of determining when to change altitude. There is very little interpretation necessary. A pilot flying in the 1940s flew approaches comprised of range stations and any aviation book from that era will describe how simple it is. It’s just a matter of flying an intercept heading until picking up Morse code for either the letter “N” or the letter “A.” This will tell the pilot which side of one of the legs the aircraft is located. Now the pilot turns to the inbound course and serpentines along a radio wave, listening carefully until a solid tone is heard in the headphones. This means the aircraft is , a-hem, “on the beam” (no kidding, that’s where the expression came from). However, when the pilot ceases to hear a steady tone and, instead begins hearing Morse code for the letter “A” (dot-dash) it means the aircraft is on the left side of course. If the Morse code letter for “N” (dash-dot) is heard, it means the pilot is on the right side of the course. As the pilot dos y-does along the radio wave, there will suddenly be silence. This is the “cone of silence” and was in them-thar days the final approach fix. Here the pilot drops the landing gear and flaps, starts a stopwatch, maintains a predetermined airspeed and descends. After so-many-minutes and so-many-second elapse the pilot looks up and if no airport is in site the missed approach is executed, only this time, the pilot flies outbound on a corresponding “beam” while cleaning up the aircraft, climbing and keeping the tone in his earphones from becoming either a Morse code dot-dash or a dash-dot. Simple, eh?

True story: I actually was flying with a guy that whined that he had to push a button on the flight director to guide him through a missed approach; he thought it should be automatic. Sigh.

Take some time to take a walk “forward into the past” of aviation history. You’ll discover that a lot of juicy aviation came way before today’s automation and next-gen hype. You might discover that the reason flying seems so advanced today was because pioneers had to be creative and ingenious and developed schemes that became the fundamentals of how things are done today. First autopilot? 1914. Radar? 1904. Long range global navigation? 1942. Aircraft anti-ice system? 1944. Retractable landing gear? 1911. Pressurized aircraft? 1921. Although today’s advancements are impressive, they are really nothing but tweaks and improvements on things that have been around a long time. Developing the first anything required incredible ingenuity and patience. Improving on what is already here doesn’t seem so amazing in the context of an inventor starting a design from a blank sheet of paper.

The best part of educating yourself about aviation history is the realization that the path to what we have today was slow, frustrating and painful. It didn’t happen through an instantaneous process of computer modeling and CAD algorithms. A pilot who makes the decision for aviation to be his or her life’s work should respect the profession enough to know its beginnings and storied development. When you do, you will appreciate what you have and will never take it for granted.

Vern Weiss

Source:

1 – Capt. Jepp and the Little Black Book by Flint Whitlock and Terry Barnhart, Savage Press, 2007.

Leave a Reply