Juliane Koepcke’s Incredible Story of Survival

Juliane Koepcke was born in Lima in 1954, to Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke. She had what many, herself included, considered a lucky upbringing, filled with animals. Her first pet was a parrot named Tobias, who was already there when she was born. She also became familiar with nature very early in life. She was closer to her mother, but the three Koepckes, father, mother and daughter, formed a closed bond over a shared love of nature. Still, at times, Juliane felt lonely as her scientist parents spent countless hours and late nights immersed in research, working together or with other respected scientists.

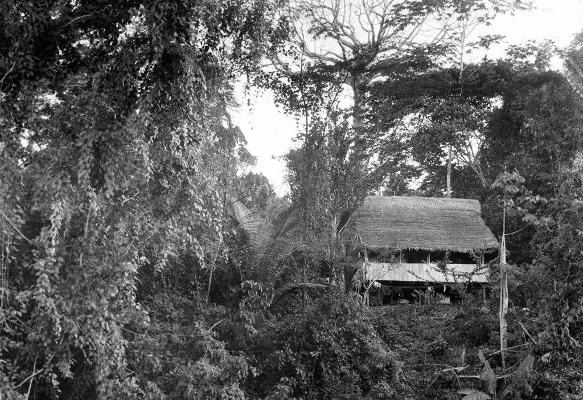

Then, in 1968, when Juliane was 14, her parents moved, with her in tow, from Lima, Peru deep into the remote jungles of the Amazon. They built a new research station on stilts in the jungle, and dubbed it Panguana, after a native bird. Here, they took on and would continue to further Juliane’s education themselves.

There was no running water, no electricity and very little in the way of outside influence or contact.

Homeschooling Jungle Survival Skills

During her time in the Amazon, Juliane’s parents also taught her how to survive and / or deal with a variety of perils, from poisonous bugs, snakes, and piranhas to the flesh eating fowl that inhabited the surrounding jungle. And they taught her life lessons for living in the jungle, including how to successfully navigate over terrain choked with undergrowth and sprawling tree roots, that you should never put your boots on without shaking out the poisonous spiders first and how to follow flowing water if she ever became lost.

As Juliane and her father went for morning jungle walks, she received math lessons. Plant, animal and insect identification were also a large part of her education. She spent 18 months here with her parents and soon grew to love the jungle almost as much as they did.

High School Graduation

Eventually, despite the excellent education she was receiving, the school system stepped in to lay down the law. If she wanted to graduate from high school, Juliane had to return to Lima to finish classes and take her exams. So, in March 1970, she did just that. She returned to school, finished all her work, passed her exams was scheduled to fly back and meet her parents a few days before Christmas in 1971. However, her graduation ceremony and a school dance were scheduled for the 22nd and 23rd, conflicting with her plans to fly back on the 20th. Her mother, in town to collect Juliane for the flight back, understood the importance of graduation and dances to her teenage daughter and decided to postpone a few days.

Juliane, who’d been saving up to purchase a gorgeous, patterned blue dress, attended both the ceremony and dance.

Trouble Booking a Christmas Eve Flight

The next day, Christmas Eve, Juliane and her mother prepared for the flight back. All of the flights were booked solid, except for one with LANSA airlines. Despite their horrible safety reputation, including a previous crash the year before that killed 99 out of 100 people on board, and her father’s request that they “Please fly with anyone else,” her mother took the chance and booked two seats, declaring, “I think it will be OK.”

Flying into a Thunderstorm

Lansa Flight 508 was a Lockheed L-188A Electra Turboprop1, and it was bound for Pucallpa. They took off from Lima just before Noon, and the airliner climbed to roughly 21,000 feet. A short time later, things started to get dark and the airplane began encountering turbulence. Moments later, they were engulfed in a thunderstorm, and terrifying shaking ensued. The passengers screamed as desserts, Christmas presents, drinks and flowers filled the air. The baggage compartments popped opened, and suddenly luggage flew through the air as well.

The clouds became darker and darker and the flight became more turbulent. Then we were in the midst of pitch-black clouds and a proper storm with thunder and lightning. It was pitch-black all around us and there was constant lightning. Then I saw a glistening light on the right wing… The motor was hit by lightning. – Juliane Koepcke

It was 12:36 PM when lightning struck the right wing, and ignited the fuel tank. Juliane’s mother turned to her and spoke her last words, “This is the end.” It was too hard a hit for the Electra and the right wing tore away moments later. This led to extensive structural failure of the aircraft, and as it entered a steep dive, it began disintegrating.

I heard the incredibly loud motor and people screaming and then the plane fell extremely steeply. And then it was calm-incredibly calm compared with the noise before that. I could only hear the wind in my ears. I was still attached to my seat. My mother and the man sitting by the aisle had both been propelled out of their seats. I was free-falling, that’s what I registered for sure. I was in a tailspin. I saw the forest beneath me-like ‘green cauliflower, like broccoli,’ is how I described it later on. Then I lost consciousness and regained it way later, the next day. – Juliane Koepcke

Juliane, still belted into her seat, fell for roughly 2 miles before impacting the jungle below. It is not known exactly how she survived, but many people believe that the row of seats she was strapped to played a key role, possibly rotating like a helicopter as she fell, slowing her rate of descent. They may have also helped when she struck the trees, cushioning the impact and slowing her further as it crashed through the multiple layers of vegetation.

I was definitely strapped in [the airplane seat] when I fell. It must have turned and buffered the crash, otherwise I wouldn’t have survived. – Juliane Koepcke

Alive, Alone and Stranded in the Amazon

For the next 19 hours, Juliane Koepcke faded in and out of consciousness. She finally came to and managed to remain conscious the following morning. She later credited the heavy rainfall for bringing her back to consciousness.

Juliane was dressed in only a sleeveless mini-dress, and was missing her glasses and one sandal. She had a broken collar bone, a torn ACL, a partially fractured shin, a strained neck vertebra, several deep cuts on her arms and legs and one eye that was swollen shut. Her injuries were serious, to be sure, but it was nothing short of a miracle that was all that happened to her, given that she’d just survived a two-mile fall.

Her mother’s seat had landed next to Juliane, though it was empty. So in spite of her bad condition, Juliane’s primary concern became finding her mother. She began searching the area around her crash site, crawling on all fours and calling out periodically. She moved in small circles, staying close to her seat, and memorized the location and marking on surrounding trees so she could keep her bearings ins spite of her poor vision.

After spending a good part of the day searching, Juliane had failed to turn up any trace of her mother. She did, however, find a bag of sweet candy, which turned out to be vitally important, as it would be the only sustenance she would have for her coming ordeal.

Juliane heard the overhead hum of circling aircraft. The overgrowth was too thick to allow the aircraft to see her, and she realized she needed to head for more open country if the aircraft were going to have a shot at noticing her.

After the hum of the plane dimmed and finally disappeared, Juliane became aware of another sound: the dripping and gurgling of running water. She found a nearby spring, which fed into a tiny stream. This was huge for two reasons: she had fresh water, and based on lessons she’d received during her time at Panguana, she knew she could follow the course of this tiny spring-fed stream to larger water sources, such as a river, and hopefully to civilization or rescue.

Juliane Koepcke Begins the Trek to Civilization

And so the battered seventeen year Juliane Koepcke set out, following alongside the tiny stream. Drawing on more of her knowledge of the jungle, she knew that she had to be wary of snakes, poisonous and otherwise. So as she walked, she would test the area in front of her by throwing her remaining sandal ahead, then moving forward to pick it up, and tossing it again. It was difficult going at first, because in addition to snake testing, she also often came across huge logs and masses of gnarled roots in the way, and had to climb over or under them.

Eventually, the tiny stream widened and grew to a more respectable size, and carved a small streambed that was often dry in portions. This allowed Juliane to walk beside it more easily. Finally, around 6 in the evening, it started getting dark. Juliane found a protected spot in the streambed where she could spend the night, and hunkered down.

The next morning, as she continued walking, she heard the call of the King Vulture. She recognized the call from when she’d encountered them before during her time at Panguana, and figured there were probably dead bodies nearby. The next day she was proven right when she came across a row of seats, with three passengers still strapped to it. The seats were upside down, as the passengers had landed headfirst.

I couldn’t really see that much, only people’s feet pointing up. I poked their feet with a stick. I couldn’t touch the dead bodies. I couldn’t smell anything and they hadn’t been eaten yet or started to decay. I mean, sure, decay must have started, but I couldn’t notice it. I could tell it was a woman because she had polished toenails and the others must have been two men, judging by their pants and shoes. I moved on after a while, but in the first moment after finding them, it was like I was paralyzed. – Juliane Koepcke

After this encounter, on the 28th of December, Juliane’s watch stopped working. It was the fourth day of her ordeal. By this time, the small stream had grown into a larger stream, and now a small river. It was the rainy season, meaning Juliane wasn’t finding any fruit to pick, and she’d eaten her last candy. She also didn’t have a knife to cut the palm hearts free from the palm tree stems, or any way to cook roots or catch fish. And she didn’t dare to eat anything else. She had water, thanks to the river, but food became more and more of a problem.

Ironically, as she continued her trek, she remained a food source for the insects of the jungle: Ants, beetles, mosquitoes, flies (including ones that laid eggs under her skin or in wounds) and even wild bees without stingers that hung from her hair. On the fifth or sixth day of her trek, Juliane heard a noise that pulled her out of her funk: the call of the hoatzin. She remembered this bird’s call from her time in Panguana, and that it was a bird that nested exclusively near open stretches of water. Areas where she could be found or maybe find civilization.

With renewed euphoric energy, Juliane pushed ahead. She arrived at the bank of a large river, but found no sign of anyone. She heard planes in the distance, but after a time, the sounds faded. Juliane became angry. Angry at the pilots for leaving before they found her. Angry at the empty landscape. Angry that she seemed no closer to being found. This anger gave way to despair, but Juliane recovered quickly. She decided that where there was a river, there would be people. She had to push on.

Juliane and the River Trip

The river presented new problems. The banks were too choked with thick undergrowth, so Juliane walked through the shallow waters at the edge of the river. She picked her way carefully, knowing that stingrays nested in these shallow waters. It was incredibly slow going, and eventually Juliane decided to swim out to the middle of the river instead. She knew stingrays didn’t venture out into the deeper water, and though there were piranhas, she also knew that they were generally only a problem in standing water.

As the sun set, Juliane swam to shore to find a place to hunker down for the night. Her insect bites, infected and painful, meant she was unable to sleep at night. This started a new cycle. Juliane swam out into the middle of the river, covered as much distance downstream as she could, and then swam back to the shore to spend a sleepless night huddled up on the bank. One morning, after a few days of this, Juliane felt a sharp pain in her upper back. She reached back and touched it, and when she brought her hand back, it was streaked with blood. She was being burned by the sun while floating down the river during the day.

She learned later that she had second degree burns.

As the trek downriver continued, Juliane began hallucinating. As she drifted, she saw the roof of a house on the riverbank, or believed she could hear the clucking of chickens. She also began to fantasize about food, and dreamed up elaborate meals. Every new morning, it was harder for Juliane to convince herself to get back in the water.

It was now the tenth day of Juliane’s incredible ordeal in the jungle. As she floated down the river, she encountered logs constantly. It taxed her already meager reserves of energy to climb over them, and she had to be careful not to injure herself further or break a bone as she bumped into each new log. Finally, after an exhausting day, she swam to shore, finding a suitable gravel bank where she dozed off for a few precious minutes. She awoke to a startling sight: there was a boat in front of her.

Civilization, At Last

Not believing her eyes, Juliane crawled up to boat, and reached out to touch it. It was not a mirage. Juliane then noticed a small, beaten path the led up the riverbank. At this point, accounts differ on where this next event happened, but they generally agree on what happened, and how it happened. Juliane had a wound on her arm that was infected with maggots. She’d previously attempted to squeeze some out, but had had no success. Once again, her time at Panguana served her in good stead. She remembered a time when her father had removed maggots from the family dog, using diesel fuel to force them to the surface.

And this is where there’s some debate. Some sources say the Juliane found fuel in the fuel tank on the boat’s motor. Others say she found it later, up at the hut above the bank. But wherever she found it, Juliane poured the fuel on her wounds. As she had seen before, this caused the maggots to surface. She picked them from her wound one at a time, thirty-five in all.

Juliane followed the small trail up the bank, which led to a small hut. However, in her exhausted state, the short trek took several hours. She’d hoped to find someone in the hut, but no one was there. She spent what remained of the night in the hut, able to finally sleep for a period of time. She woke in the morning, her eleventh day in the jungle, but still no one had shown up.

It began to rain, and Juliane wrapped a tarp she found in the hut around her shoulders. The rain stopped in the afternoon, but she was unable to get to her feet, and decided she would rest another day before moving on. As dusk approached, she heard voices. Juliane dismissed them as hallucinations, but they grew louder. Three lumbermen emerged from the jungle, and were startled to find a disheveled, badly wounded teenage girl in the hut.

She told them in Spanish that she was a survivor of the LANSA crash, and her name was Juliane.

That night, the three men dressed her wounds and fed her some food. The next morning, they loaded her into a canoe and took a seven hour ride downriver to a lumber station. Here, a local pilot agreed to fly her to a hospital. It was a short, fifteen minute flight, and after she arrived, Juliane was reunited with her father.

From her hospital bed, Juliane gave information to the researchers that helped them locate the wreck and more bodies. On January 12th, searchers found Maria Koepcke’s body.

Life After the Crash

I had nightmares for a long time, for years, and of course the grief about my mother’s death and that of the other people came back again and again. The thought Why was I the only survivor? haunts me. It always will. – Juliane Koepcke

By March of 1972, Juliane Koepcke had recovered and returned to school in Lima. She planned to study for two years, and then take the entrance exam at a German university. However, she continued to be constantly followed and beset by journalists and others who were interested in her story. Her father suffered a panic attack and decided it was best to send her back to Germany immediately. She would live with her Grandmother and Aunt. Juliane was not happy about this, and it caused a rift between her and her father.

I was very angry. Panguana and my school were the only things left for me. It took about two years to accept it. But fortunately I had a very nice school in Kiel in northern Germany and very nice friends. But with my father it was very difficult. – Juliane Koepcke

A couple of years later, her father returned to Germany as well, and they eventually reconciled. Following in her parents footsteps, Juliane studied biology at the University of Kiel, and graduated in 1980. She went on to earn a doctorate from Ludwig-Maximillian University and even returned to Peru, and Panguana, to conduct research on bats for her thesis paper. Her father suggested it, noting that the area had an abundance of bats. She spent eighteen months there, and identified fifty-two bat species.

Years later, in 1998, film director Werner Herzog approached Juliane (now married, Juliane Diller, and serving as a librarian at the Bavarian State Zoological Collection in Munich) about making a documentary about her story. Surprisingly, he had a personal connection to the incident. He had been in Peru at the time, location scouting for his film Aguirre, the Wrath of God, and he’d been scheduled on that same fateful Christmas Eve flight. A last minute change in his itinerary had caused him to cancel his reservation.

He offered to take her back to crash site as part of the documentary.

He [Werner Herzog] helped me towards working through my past. His empathetic questions and his ability to truly listen, as well as the chance to return to the site of my terror, were the best therapy. – Juliane Koepcke

Juliane agreed, and returned with Herzog to the crash site. The resulting hour long documentary, Wings of Hope, came out in 2000. During her time there, Herzog also convinced her of the necessity of preserving her parents legacy at Panguana. She worked to expand the size of the Panguana research area from 460 to 1,730 acres. And in 2011, through working with the Peruvian Government, she was able to help get it declared a nature reserve, permanently protecting it from logging, hunting or human colonization.

After the film, Juliane decided it was time to write a book about her experience. While she conducted research for the book, Juliane came across a letter from her father to her aunt (his sister) mailed in 1972, after Juliane had been sent back to Germany. In the letter, her father told her aunt that Juliane was forbidden from returning to Panguana (something he apparently softened on after some years). After reading this, Juliane cried.

I always suspected that for him it was a problem that I survived and not my mother. But then I understood. He was paralyzed with grief. That Christmas was the first anniversary of her death. He was completely alone in Panguana, alone with his grief, and the last thing he wanted to see in those moments was me because I looked a lot like my mother and that was a problem for him. – Juliane Koepcke

Her father had passed away in 2000, at the age of 87. But Juliane believed that her father never recovered from losing his wife, and had given up before that.

His life was finished. He lived like a machine. After he died I found a small candle and it was named the Panguana candle and every year on Christmas Eve – the official anniversary of my mother’s death – he put the candle by his bedside and lit it. – Juliane Koepcke

Juliane also discovered another, shattering piece of information from her father’s letters. Her mother had apparently survived the fall from the plane as well.

My father thought she’d survived for nearly two weeks – perhaps up to January 6, because when he went to identify her body it wasn’t as decomposed as you’d expect in that environment – it’s very warm and humid and there are lots of animals that would eat dead bodies. He thought she’d broken her backbone or her pelvis and couldn’t move. – Juliane Koepcke

This information was hard for Juliane to take.

My husband says, “Don’t think about it. You cannot change it.” But it bothers me very much. I think, what must it have been like for her in those last days there? – Juliane Koepcke

Juliane finished the book, and it was released on the 10th of March, 2011 with the title Als Ich vom Himmel fiel (When I Fell From the Sky). The book was well received, and even won awards.

In the lonely nights I passed in the forest I said to myself, if I survive this, I will make something important for humanity and nature. Those are great words, but only words and up to now I have been thinking, have I achieved this or not? And that is another way of feeling guilty. – Juliane Koepcke

Wait … What About all That Flying?

As a small sidenote, in addition to the many trips back and forth in the intervening years after the crash, Juliane returns to Panguana with her husband Erich twice a year. So, wait. How does she deal with all the long flights between Germany and Peru?

Long flights are difficult. I get so tense that even sleeping pills don’t work. Red wine is always good. And a whisky. – Juliane Koepcke

Wow. I am beyond impressed. I’m not sure I would ever be able to set foot in an airplane again, after an experience like that.

Footnotes:

1 – In a sad twist of irony, this particular Lockheed Electra was LANSA’s last remaining aircraft, and a couple of weeks after this crash, the company lost their operating permit.

Offsite References for Juliane Koepcke:

Sole Survivor: the Woman Who Fell to Earth, The Telegraph

I Fell 10,000ft to Earth Strapped to a Seat and Lived, Daily Mail

Wings of Hope, in it’s entirety:

In the DOF Pilot Shop:

When I Fell from the Sky, by Juliane Koepcke

Leave a Reply