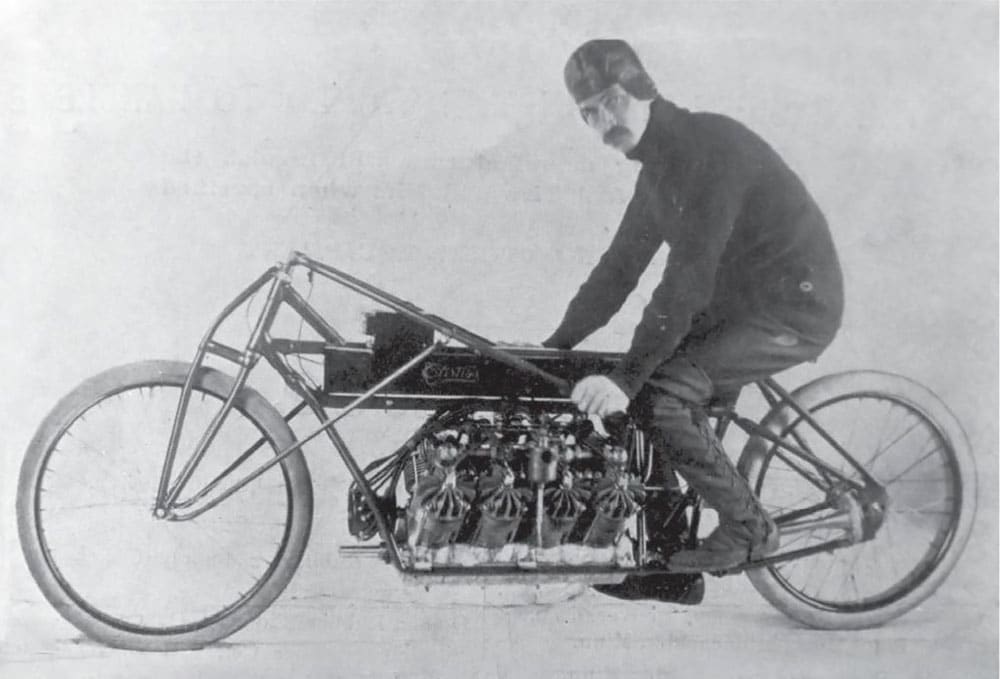

Glenn Curtiss, the real Fastest Man Alive.

Some people are born for greatness, others for happiness, and still others for love. Glenn Hammond Curtiss was born with a need for speed. Born in Hammondsport, a sleepy town in the Finger Lakes Region of Upstate New York to Canadian expat Frank Richmond Curtiss and Lua A. Andrews, Glenn was an innovator who dreamed of defying physics from an early age.

Glenn Curtiss: Early Life

Frank Curtiss was the villages harnessmaker, and he had a small workshop at the tip of Hammondsport’s main street. Frank and Lua had two children, Glenn Hammond (May 21, 1878) and Rutha Curtiss (February 15, 1881) and lived a happy quiet life, until tragedy struck and struck again.

In August of 1882, Frank died of a stroke, leaving his small family in the hands of his wife, Lua and his mother. At age 6, Rutha fell ill with a severe case of meningitis, which spared her life but stole her hearing. Lua picked up her family and moved them to Rochester, NY, so that Rutha could be given a chance at a normal life at the “Western New York Institute for Deaf-Mutes,” now known as the Rochester School for the Deaf. Rutha attended the school for 4 years from September 1889 to June 1903. During this time, Lua attended the State Teachers College in Geneseo to better support her family.

Glenn, who had remained in Hammondsport to finish his schooling, moved to Rochester to join his family after graduating the 8th grade. When Lua graduated from the State Teachers College, she opened a storefront school in Rochester while Glenn got a job as a stencil maker and film stock assembler at Eastman Dry Plate and Film Co., now known as Eastman Kodak.

Dreaming of Speed on Two Wheels

When Glenn Curtiss had saved up enough money, he left his factory position and bought a bicycle, becoming a bike messenger for the Rochester branch of the Western Union Company, a financial service. In the same way tragedy befell the Curtiss’s all at once just a few years ago, it now appeared as though things were finally going to go right for the small family.

On April 1, 1895, Lua remarried and moved in with J. Charles Adams, an old flame. Adams owned and ran a large vineyard on the banks of Seneca Lake. Though the new family stayed in Rochester for a time, when Lua became pregnant with Glenn’s step-brother and future business partner George Carl Adams, they moved back to the Adams’ vineyard in Rock Stream, New York. During this time, Glenn worked on his stepfather’s vineyard while pursuing his passion for cycling.

The Hammondsport Wheelman’s Club provided multiple services to Glenn in his early career building and repairing bicycles; firstly, it offered him a small community of like-minded people to further fuel his passions for cycling and building, and secondly, it created a loyal customer base for his budding business. It was during this exciting time in Glenn’s young adulthood that he met his closest friend and true love, Lena Pearl Neff, daughter to a Michigan raised sawmill superintendent.

Young Lover and National Champion

On March 7, 1898, the young lovers Lena and Glenn were married. Glenn’s business was booming, and in addition to his father’s storefront in Hammondsport, he opened shops in Bath and Corning, New York. As can be predicted with powerful minds, Glenn was always moving forward and searching for the next bigger, better, and faster piece of machinery to get his hands on. After establishing himself as a National Champion cyclist at county fairs across the country, Glenn decided to follow that need for speed and rig a small engine to a bicycle. The first attempt, however, was less than successful, with Glenn remarking after the fact that, “…it almost tore itself loose from the frame.”

Not one to give in to failure, Glenn’s initial attempt at the motorcycle further ignited his interest in the concept, and only a few years later, he was able to open the G.H. Curtiss Manufacturing Company, with the financial support of friends and hopeful bankers.

Hercules Can Go the Distance

By 1902, Glenn Curtiss was selling his own motorcycles, called the Hercules. The Hercules often put heavier, and thus slower, motorcycles to shame in races, such as the Indian or the Harley Davidson. Because of this, the Hercules line of motorcycles gained a well-earned reputation for being the fastest, lightest motorbikes out there.

Between 1903 and 1904, Glenn became the first ever American Motorcycle Champion, establishing the first of his many world records with a 56.4-second mile. Glenn’s later invention of the handlebar throttle helped him earn a new ten-mile speed record and the title of the “fastest man in the world,” setting a speed record for a V-8 engine motorcycle at 136.36 mph, a record which would stand until 1930. It was during this time that he gained nickname Hell-Rider, reportedly coined by newspaper reporters after they overhead Indian motorcycle riders say at a competition ‘Oh Hell, he’s here,‘ in regards to Glenn.

King of the Air Takes to the Skies

The focus and limelight aimed at Glenn Curtiss wasn’t only from the speed freaks and cyclists of the world, either. The G.H. Curtiss Manufacturing Company was making quite a name for itself as well, and in 1903, famed balloonist Captain Thomas Baldwin requested an engine powerful enough to bring his airship concept to life.

Shortly after, with Baldwin’s financial assistance and the creation of an air-cooled two-cylinder 5 horsepower motor, the California Arrow made the first successful dirigible flight in America. The California Arrow was Glenn’s first official step into the new and exciting world of early aviation. Glenn’s growing interest in aviation led to him offering his engines to the Wright Brothers, who denied him without a second thought. Orville and Wilbur Wright were reported to be fiercely independent to the point of blindness. Though Glenn wouldn’t recognize the significance of this less-than-pleasant start to their relationship, he would find the Wright Brothers to be recurring antagonists in his tale.

The success of the California Arrow won Thomas Baldwin $25,000 (approximately $632,022 adjusted for inflation) and won Glenn a seat on inventor Alexander Graham Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) as the Director of Experiments.

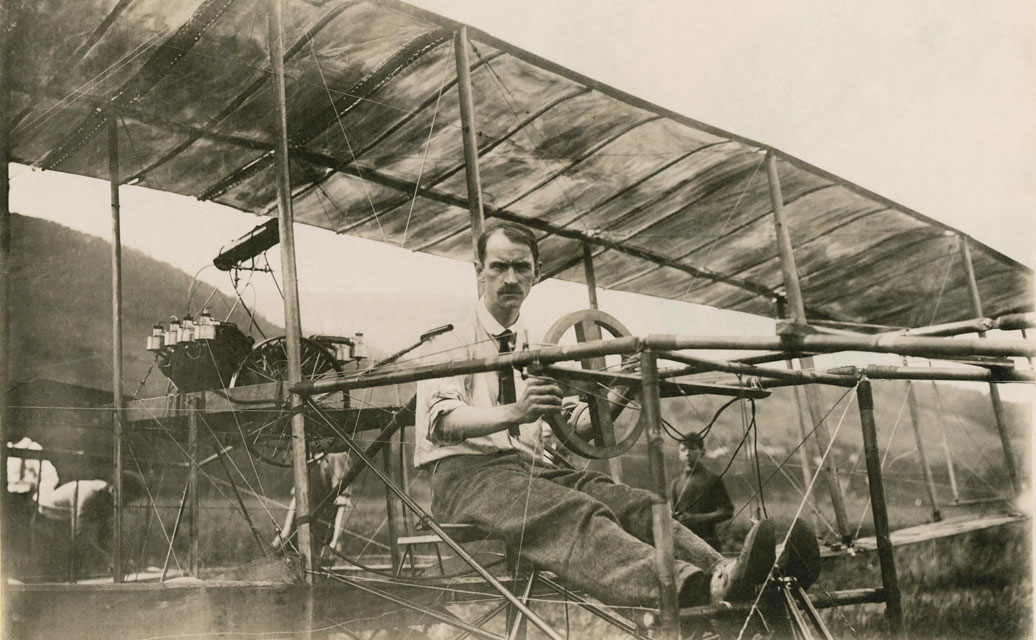

Glenn Curtiss “Flew Like a Real June Bug”

In 1908, Glenn Curtiss and the AEA created the ‘Red Wing,’ (officially the Aerodrome #1), which became the first publicly witnessed flight of a powered aircraft, as well as the first ever flight by a Canadian pilot. The Red Wing had a 43-foot wingspan and a V-8 engine, but only managed to fly for roughly 20 seconds, covering a distance of 319 feet after lifting off the frozen surface of Keuka Lake in March of 1908. After a mechanical malfunction led to a portion of the tail falling off, the proto-plane crashed and was damaged beyond repair.

In May of that same year, Glenn piloted the latest incarnation of experimental aircraft, the ‘White Wing,’ for a staggering 1,017 feet of controlled flight. The White Wing would be the first American aircraft to use ailerons for the purpose of control, a matter of record that would be fiercely combated by the Wright Brothers who tried to patent every moving panel on an airplane.

Less than a month later, on July 4, 1908, Glenn again took to the skies in a record-breaking experimental aircraft nicknamed the ‘June Bug,’ also outfitted with ailerons. The plane survived an unassisted take-off and remained airborne for nearly a mile (5,090 feet), which earned him the Scientific American Magazine trophy. After the June Bug was fitted with floats and failed at achieving a water take off, the AEA moved onto the next project, another record-breaking aircraft called the Silver Dart (which became the first airplane to fly in Canada).

Most people who have as profound an impact on an area of study or an industry like Octave Chanute did on aviation tend to spend most or all of their lives involved in that pursuit. But for Chanute, though he became interested in aviation at a young age, it wasn’t until his late 50s that he was able to start actually pursuing his interest in aviation, and his 60s before he began the flying experiments and glider testing for which he is most often remembered. But in the roughly 21 years he was heavily involved in aviation, he had an immense influence on the field of study just as it was preparing to take flight. [Click here to read more…]

The Start of the Patent War

During this period of success for Glenn Curtiss, in 1908, the Wright Brothers saw fit to warn him not to infringe on their patent by either profiting from flying aircraft that used ailerons, or selling them. See, after the Wrights had failed to secure a patent in 1903, they hired a patent attorney who was able to secure them one in 1904 for a ‘flying machine.’ As part of the patent, it laid claim to a new method of controlling a flying machine (powered or not), describing wing-warping, the Wright’s less-workable precursor to ailerons. But when other aviators developed and used ailerons to achieve the same control, the Wrights claimed that it was infringing on their patent and the methods described in it, and the US courts agreed that the Wright patent covered ailerons.

Curtiss refused to pay any fees, and in 1909, the Aeronautical Society of New York requested of Glenn a new type of experimental aircraft, which would become the Curtiss No. 1. He sold it to them, and the Wrights carried through on their threat, suing Curtiss and kicking off years of legal battles dubbed ‘The Patent Wars.’ Curtiss was only the beginning, and the Wrights sued a variety of people and businesses both in the US and Europe. The Curtiss people responded to all of this by suggesting that if someone jumped into the air and waved their arms, the Wrights would sue them. While their European lawsuits were only partially successful, the US litigations brought development in the field of aviation to a virtual standstill for a number of years.

After his successes working with the AEA, Glenn Curtiss joined forces with Augustus Herring, a hopeful (but less successful) aviation pioneer who, among other things, was a test pilot for Octave Chanute’s gliders. Together, they formed the Herring-Curtiss Company in 1909, where Glenn gave life to his first independently designed and built aircraft, known as the ‘Golden Flyer.’

Curtiss was interested in partnering with Herring for many reasons, not least among them being airplane patents Herring claimed to have that predated the Wright’s patent. And though he had been involved in patent work predating the Wright’s patent, he was never officially granted any patents. Apparently, while a test pilot for Octave Chanute, Herring submitted his aircraft patent as early as May 1896, but it was denied. Herring returned to work for Chanute a couple of years later, apparently only with the goal of getting his patent approved. As the US Patent Office didn’t want the patent, Chanute combined his ideas with Herring’s and sent the resulting patent to Thomas Moy (an English engineer and patent agent) in England. This was not successful either, and over and over, for the next ten years, Herring revised and resubmitted his patent, convinced that he had something important, but to no avail.

When Curtiss found out that Herring had no actual patents, he declared bankruptcy, and the short-lived Herring-Curtiss Company was dissolved less than a year after it was formed. Curtiss then relaunched the newly formed Curtiss Airplane Company. This would be the seed for a later patent related lawsuit Herring would pursue against Curtiss.

Gilded Wings Win Gold

The Golden Flyer managed to take Glenn an unprecedented distance of 24.7 miles, which set a new world record and bagged part two of the Scientific American trophy. Bolstered by this success, Glenn entered a series of competitions that put him up against Europe’s top 40 planes and pilots, which would eventually earn him the first Gordon Bennett Trophy for his average speed of 46 mph.

Determined to continue his winning streak, Glenn entered the Golden Flyer in the first International Air Meet (Grande Semaine d’Aviation) in Reims, France, but crashed the plane before the competition could take place. Instead of repairing the badly damaged Golden Flyer, Glenn created the Curtiss No. 2, or ‘Reims Racer;’ a lighter, faster, an open-frame biplane with two-bay wings of equal span (34 feet), tricycle landing gear, and large ailerons. Powered by the record-breaking Curtiss OX V8 engine specifically lightened for speed and maneuverability, Glenn blew away the competition, including two Wright Brothers airplanes, and won the first place prize for speed.

It is hard enough for anyone to map out a course of action and stick to it, particularly in the face of the desires of one’s friends; but it is doubly hard for an aviator to stay on the ground waiting for just the right moment to go into the air. – Glenn H. Curtiss

After his successes in Europe, Glenn returned to New York to become the first aviator to fly from Albany to New York City, following the Hudson River. Whether it was the fame or $10,000 purse that inspired him, we may never know, but Glenn designed and built a completely new airplane he called the Hudson Flyer. Winning the prize money and nationwide recognition, as well as the third instance of the Scientific American competition, Glenn finally convinced the world that airplanes would have practical uses outside of entertainment.

Before the Air Force, There Was Curtiss

In 1910, Glenn Curtiss became determined to convince the Navy of the military applications of aviation. Lt. Jacob E. Fickel, an Army officer, accompanied Glenn for an aerial demonstration of the usefulness of airplanes in combat, as well as structural integrity to compensate for the added weight and stress. The two men flew above the Sheepshead Bay Race Track near Hammondsport for a bombing simulation. Lt. Fickel became the first man to fire a gun from a plane when he shot a rifle at a target on the ground, proving that planes wouldn’t be destroyed by the intense recoil of early weaponry.

Not too long after that success, one of Glenn’s pilots, Eugene Ely, managed to take off from what would technically become the first aircraft carrier, the U.S. Navy’s scout cruiser Birmingham. Ely would, the following year, make the first ship-borne aircraft landing on the USS Pennsylvania. After these undeniable military successes, Glenn would open the first US Navy Aviation School on North Island in the San Diego Bay. After Glenn personally piloted the first water takeoff and landing, the Navy ordered two Curtiss A-1 hydroplanes, earning him the title of the “Father of American Naval Aviation.”

Modern Warfare to Patent Wars

As the groundwork for the first World War was being laid, Glenn Curtiss looked for more ways to support his country and allies in the air. In 1913, he traveled to Thomas Sopwith’s factory in England, hoping to aid and gain from Sopwith’s tractor plane productions. Unlike any of the Curtiss planes, Sopwith’s planes had their propellers in front of the wings, effectively pulling it through the air as opposed to pushing the entire weight of the plane. Using this technique, Glenn cranked up the power and produced over 15 versions of the Curtiss planes in a few years, including the history-making warplane, the JN-4, or “Jenny,” which would become the barnstormer’s plane of choice in the Roaring 20’s. His hard work and furious determination gave him the honor of manufacturing more aircraft than any other American during WWI.

Beachey’s passion for flying led him to follow in his brother’s footsteps, and pursue a position working for Thomas Scott Baldwin, a pioneering balloonist. Between Lincoln’s experience with machinery and Baldwin’s experience with balloons, they created the California Arrow, a dirigible powered by a 7-HP Hercules motorcycle engine manufactured by Glenn Curtiss, an aviation pioneer and eternal rival of the Wright Brothers. Lincoln’s first step toward becoming a pilot was the Arrow’s first flight on August 3, 1904, at Idora Park in Oakland, California. Unfortunately, the slow-moving [Click here to read more…]

Also in February 1913, the Wrights won their initial patent case against Curtiss, but the decision was appealed. In January of 1914, the initial verdict was upheld in favor of the Wrights, though the Curtiss company was able to continue to avoid paying any penalties through legal maneuvering.

As parts of the world stood reeling from the outbreak of WWI, the Smithsonian began trying to pin down the whirlwind of aviation history made in the last decade. Their first order of business was to determine who created the first airworthy plane. There had been a war raging between the Wright Brothers and Samuel P. Langley for years previously, and it looked like the Smithsonian was placing more stock in Langley than the Wright Brothers.

So naturally, the Smithsonian requested that Curtiss (much to the displeasure of Orville Wright) determine whether Langley’s Aerodrome was “the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight,” and sent the plane in question up to Hammondsport, New York. Glenn and his team were capable of flying the Aerodrome, but only after some serious modifications, and even so, the plane wasn’t aloft more than a few minutes at most. However, that was apparently enough for the Smithsonian, who displayed the Aerodrome in the museum as the first plane capable of carrying a useful load and sustaining free flight, much to the dismay of Orville Wright. Wilbur had died two years prior of typhoid fever, leaving Orville to fight the never-ending battle for recognition alone.

Luckily for the Wrights, Orville’s older brother Lorin was witness to the Aerodromes flight in Hammondsport, where he extensively cataloged the modifications Curtiss made that allowed the plane to fly. According to the Wright family, the modifications made to the aircraft prove that the Aerodrome was unable to fly before Curtiss got his hands on it, proving that Langley couldn’t have piloted the airplane capable of free sustained flight. It took decades of legal battles, but the surviving Wrights proved their case, and now the Wright Flyer is displayed in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, as the world’s first “powered heavier-than-air flying machine.”

As WWI continued, the Patent War dragged on. Finally, in 1917, with the Wright Company and Curtiss Company effectively blocking the manufacturing of new aircraft, and the US set to enter the war, the government stepped in. Forming a ‘patent pool,’ all aircraft manufacturers were required to pay a small blanket fee for use of the patents, from which the Wright and Curtiss companies would see the bulk of the proceeds.

In a final twist of humorous fate, the Curtiss and Wright companies were merged in 1929 to form the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, which still exists today, now a diversified company with ‘a long tradition of providing state-of-the-art reliable solutions through trusted customer relationships to the commercial, industrial, defense, and energy markets.‘

A Family Man and Lifelong Inventor

During the 1920s, aviation continued taking the world by storm. Years prior, in preparation for the birth of his second child Glenn Hammond Curtiss in 1912, Glenn had given up exhibition flying to better support his family after the tragic death of his first child, Carlton, just before his first birthday. And in 1920, as the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company underwent postwar reorganization, Glenn Curtiss sold his stock in the company for a reported $32 million.

Eventually, Curtiss and his family moved to Florida, where many of his new business ventures were centered. Glenn started buying up large amounts of real estate in Florida, helping to establish the cities of Hialeah, Opa-Locka, and Miami Springs and creating tourist traps such as Arabian-themed hotels and private airports, eventually building his family a pueblo-style home in Miami Springs.

However, despite these changes and involvement in new business ventures, Curtiss stayed involved in aviation.

In 1922, for example, Curtiss had engineered and built a sail-plane, or “hydro-glider” which was initially pulled by a speed boat and then eventually by a hydroplane to get it aloft. According to aviation historian Simine Short, this is the first time aero-towing was successfully used to launch a glider of any kind, though the Curtiss sail-plane never actually achieved soaring flight.

A Disheartening End For a Distinguished Man

Around the time Curtiss was partnering with his stepbrother G. Carl Adams in the real estate business, and after he’d sold his stock in his company, Glenn’s old business partner Augustus Herring showed up. He felt he was owed a piece of the patent profits, and filed a lawsuit against Curtiss in 1921. This was the start of a long battle, and though Herring died in 1926, his lawyer James Martin continued fighting for Herring’s portion of the patent profits on his behalf.

In 1930, the lawsuit required Glenn to travel to Rochester, New York, to fight the case. Unfortunately, on the way there, Glenn doubled over in pain, clutching his abdomen. Herring’s lawyers claimed he was faking it to get out of the court date, but Glenn was rushed to the hospital for an emergency appendectomy at the Buffalo General Hospital. After a seemingly successful surgery, Glenn died from a blood clot on July 23, 1930, at only 52, an anticlimactic ending to a colorful and record-breaking life.

After Glenn Curtiss’ death, Herring’s lawsuit continued to drag out for a year, until Glenn’s wife, Lena, settled the suit in late 1930 for about $500,000 in compensation. Glenn was posthumously added to the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in the air racing category and the National Inventors Hall of Fame. His memorial in the Inventors Hall of Fame reads: “Glenn Curtiss is considered the most influential man in the evolution of aviation. His keen insight into aeronautics and aviation, despite having no formal education past eighth grade, affirms his genius. He holds the Collier Trophy and the Langley Medal.”

Glenn Hammond Curtiss was survived by his only son and wife and continues to thrive in the stories and legends of aviation.

***A big thanks to Simine Short for her helpful corrections and additions regarding The Patent Wars and the Curtiss sail-plane.

Resources and Additional Reading

Leave a Reply