The Page Airport is a great place to set-up for the perfect redrock adventures.

Fly in to Page Airport if you’d like to explore some of the most beautiful, most famous, most awe-inspiring redrock sandstone formations on Earth, and likely in the whole solar system! Take a short hike to a hoodoo-filled plateau so foreign, it literally feels like you are on Mars. Engage a Navajo guide to show you Antelope Canyon – it’s even more magical in person than the photos you’ve seen. And marvel at the wildly colored layers of voluptuously rounded sandstone that form The Wave. If you visit on non-holiday winter days, you’ll likely have these natural wonders all to yourself.

You’ll get an inkling of what you’re in for as you overfly the area. Deep, twisted canyons surrounded by cliffs of vermilion litter the landscape, and of course you can’t miss the Glen Canyon Reservoir – Lake Powell – that incongruous blue set against pink Navajo sandstone escarpments

Rent a houseboat for a week and explore some of its 96 side canyons. 186 miles long, with more shoreline than the entire western U.S. coast, you could visit over a lifetime and not learn all its secrets.

Page Airport

Page Airport sits just east of town and the Glen Canyon Dam, which blocks the Colorado River, forming the Powell reservoir. The Glen Canyon National Recreation Area is upstream, with Marble Canyon and then Grand Canyon National Park downstream. The Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and Bryce Canyon National Park are to the northwest, while Rainbow Bridge, Navajo Mountain, and Monument Valley are all to the east and south. Maintain at least 2,000 ft. AGL while you ogle these areas, and remain clear of the Grand Canyon Special Flight Rules Area.

Deals on Hotels From our Sponsor:

Booking.com

Airports here are few and far between, so plan accordingly. Winds can kick up over the plateaus, especially in spring; beware of downdrafts over the canyons. Page sits near the dam but much of the area is uninhabited. Should you come in at night, use extreme caution as this remote area is so dark it can be disconcerting to a non-instrument rated pilot. Rely on the VASI lights so you don’t succumb to an optical illusion and land short. Runway 15/33 is 5,950 x 150 ft, with the short Runway 7/25 reserved for those few times when the crosswind is too extreme. Park north of the commercial terminal, where tourists come for aerial tours of the Grand Canyon and Rainbow Bridge, and Avis offer cars.

Runway Summary

| ID | Dimensions | Surface | Instrument Approaches |

| 15/33 | 150 ft x 5950 ft | Asphalt, Good Condition | RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 RNAV (GPS) RWY 33 VOR-B RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 RNAV (GPS) RWY 33 VOR-B |

| 07/25 | 75 ft x 2201 ft | Asphalt, Good Condition | RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 RNAV (GPS) RWY 33 VOR-B RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 RNAV (GPS) RWY 33 VOR-B |

Communications Summary

| CTAF | 122.80 |

| UNICOM | 122.80 |

| ATIS | N/A |

| WX ASOS | |

| CLEARANCE DELIVERY | N/A |

Terminal Procedures Summary

Approaches

Special Minimums

Closest Alternate Airports with Instrument Procedures

| UT02 – Kch Helipad – 52.4 nm NW from PGAKKNB – Kanab Municipal – 60.1 nm NW from PGAKGCN – Grand Canyon National Park – 77.8 nm SW from PGAKAZC – Colorado City Municipal – 86.6 nm NW from PGAK40G – Valle – 96.5 nm SW from PGAKCDC – Cedar City Regional – 105.5 nm NW from PGAK4BL – Blanding Municipal – 117.3 nm NE from PGA

KSGU – St George Municipal – 119 nm NW from PGA KFLG – Flagstaff Pulliam – 124.1 nm SW from PGA KRIF – Richfield Municipal – 130.2 nm NW from PGA |

FBO’s on the Field:

Geology

For those who are interested, a general overview of the area’s geology will greatly enhance appreciation of the unique land formations of the Colorado Plateau, which consists of western Colorado, southern Utah, northwestern New Mexico, and northern Arizona.

All of the details will never be known, because the geological changes have been so vast and cataclysmic that much evidence has been erased, but most geologists generally agree that between 540 million to about 70 million years ago, the areas now encompassing the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau were flat landscapes, alternately covered by vast, shallow, inland seas and vast desert sand dunes. When seas were present, organic matter collected at the bottom, and when deserts were present, dunes, sometimes hundreds of feet tall, laid down layers of wind-blown sand at various angles. Accumulating for some 470 million years into more than 15,000 feet of sediment, all of these colorful layers were compressed one upon the other as time passed into layers of shale and sandstone, whose characteristics differed according to their components, and even wind direction at the time they were laid down. The last of the inland seas was the Mancos Sea; Mancos Shale is the deposit left by this final sea, and it is exposed just west of Glen Canyon Dam.

About 70 million years ago, the North American continent drifted west and collided with the oceanic Farallon Plate, initiating a mountain-building event called the Laramide Orogeny. All the interesting north-south monoclines you see in the Colorado Plateau, such as the Waterpocket Fold (Capitol Reef), Kaiparowits Plateau, and Cockscomb, were also created during this period. Particularly with the Waterpocket and Cockscomb, you can see (from your plane or on the ground) how the layers have been warped up at an angle. More significantly, the Colorado Rockies began to rise, and also the volcanic Mogollon Highlands, north of where the Grand Canyon is now. Raising the Mogollon Highlands caused the Mancos Sea to recede to the northeast, and rivers flowing into it, including possibly the precursor to what we now call the Colorado River, actually flowed from southwest to northeast. After receding and draining, the sea was replaced by a number of freshwater lakes; the sediment from one of them forms the delicate hoodoos of Bryce Canyon.

Around 30 million years ago as the Farallon Plate was finally consumed by the westward drift of North America, the pressures that lifted the Rockies and Mogollon Highlands eased. Slowly, through faulting and erosion, the Mogollon Highlands wore down, while through extension (the stretching of the earth’s crust), the areas south and west of the current Grand Canyon began to drop into basins, leaving the Colorado Plateau relatively higher. Eventually, the rivers switched direction and began to flow south and west. The reversals are theorized to have occurred around 16 million years ago. Sometime between 12 and 6 million years ago, with the Farallon Plate now gone under our continent’s western edge, the motion between the Pacific Plate and the North America Plate formed the San Andreas Fault. Eventually, this fault ripped a long trough that was filled with ocean water, forming the Gulf of California.

With the Rockies and Colorado Plateau now elevated relative to lands south and west, rainwater flowed across the land and gathered into rivers, quickly carving endless canyons into the sandstone and shale layers. The largest of these is, of course, the Grand Canyon, which may have been carved gradually any time after about 80 million years ago, or catastrophically, when a lake called Bidahochi, east of what is now the Grand Canyon, overflowed 5.5 million years ago. As mentioned earlier, the erosion of the Grand Canyon removed so much rock that it probably destroyed all evidence of exactly how and when the canyon, as well as the Colorado River as we now know it, was formed. Water loosened the cement holding grains of sand together in sandstone, and this grit was carried down the swiftly moving river, acting like sandpaper. Water flows accelerated during each spring, but certainly to catastrophic levels during several periods when Ice Age glaciers in the Rockies melted, carving the canyon probably at least 2,000 feet deeper in just the last 2 million years.

Myriad other rivers flowed down from other mountains, like the La Sal and Abajo ranges in southeastern Utah. (The Henry Mountains, north of Lake Powell, and Navajo Mountain, south of Lake Powell, are rare laccolithic mountains—volcanic plugs that rose from below ground, but cooled before exploding into volcanoes). The immense burden of sediment from across the Plateau was carried down tributaries, into the Colorado and eventually out to the Gulf of California, where a vast and incredibly fertile delta formed.

All of this erosion created the fantastic land forms you can see today. Studies suggest that Glen Canyon, at almost a thousand feet deep, was cut only within the last 500,000 years. If you are on Lake Powell you will see the Navajo and Wingate Sandstone canyon walls towering vertically for hundreds of feet; they continue far below the water level. In Monument Valley, all that is left of the layers is the great monuments themselves, surrounded by flat terrain.

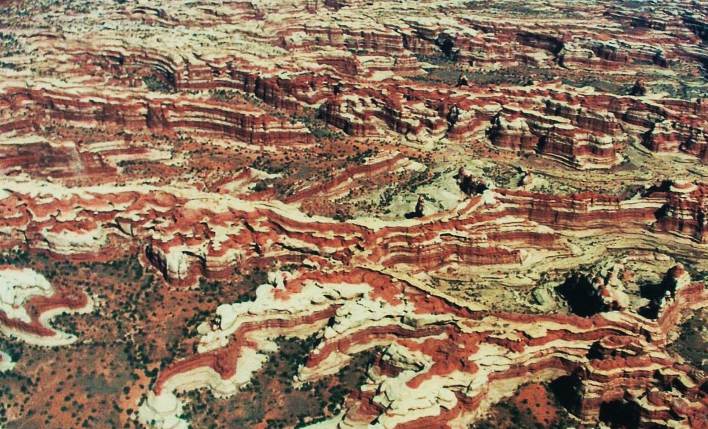

One of the most dramatic areas to observe from the air is rightly called The Maze. If you are flying to Page from the east, consider overflying the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers, and then look at the area directly to the west, which is part of Canyonlands National Park. You’ll see crazy red-and-white candystriped buttes surrounded by hundreds of twisting canyons, and you’ll understand how this area got its name. Why the stripes? The Uncompahgre Mountains were eroding quickly, producing red alluvial fans of iron-rich arkose sand, now called the Cutler red beds. These fans interfingered with underwater sand bars and shoreline sand dunes of white sand, now called Cedar Mesa sandstone. Compression hardened it into rock, and water rushing down paths of least resistance carved The Maze.

As we know, the climate has dried out and now the erosion of the Colorado Plateau proceeds at a miniscule pace compared to millions of years ago, but it does proceed. Flash floods still carve the sandstone canyons. The Colorado still carries an almost incomprehensible load of sediment, which now settles out in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Also, Wall Arch, one of the largest in Arches National Park, which are made of Entrada Sandstone, eroded to the point where it collapsed in the summer of 2008. The colorful hoodoo formations of Bryce Canyon, which form part of the second-from-top “step” of the Grand Staircase, contain some of the youngest and softest sandstone remaining and are eroding quickly. (It’s called the Pink Limestone Member of the Claron Formation, and you also see it at Cedar Breaks National Monument and the Pink and Sunset Cliffs.) If you learn the names and characteristics of the various layers and spend time exploring the Colorado Plateau, you’ll begin to see the patterns, and how the layers are almost always in the same order. A list of these layers appears in Kelsey’s books Boater’s Guide to Lake Powell and Hiking and Exploring the Paria River that are recommended later in this article.

The Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams are not the first to block the mighty Colorado River. Great volcanic flows stopped the river at least 13 times in the Grand Canyon within the last 630,000 years. One of these dams was over 84 miles long and another was over two thousand feet high! A dam so high, if it lasted long enough, would have created a vast reservoir that reached almost to Moab, Utah, 300 miles away. At least 5 of the dams did give way catastrophically, producing immense floods, one of which carried a 100-ft diameter boulder to its current resting place 650 feet high on a canyon wall.

It is interesting that while the land now slopes gradually down from the Rockies toward the Midwestern United States, erosion having provided the topsoil from eastern Colorado through the Great Plains that nourishes our wheat and corn fields, the terrain west of the Rockies falls in great steps, the “stairs” of the Grand Staircase, and more drops that go all the way to southern California.

Further reading with amazing maps depicting the ancient geologic history of the Colorado Plateau: Ancient Landscapes of the Colorado Plateau by Wayne Ranney and Ron Blakey.

History

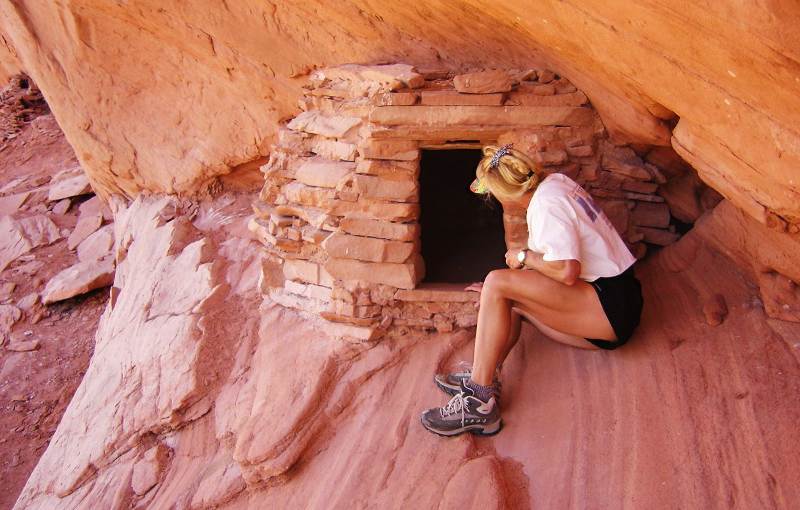

This area is full of enough Wild West tales of adventure, exploration, murder, and exploitation to fill dozens of books. Spend time in the canyons off the reservoir and you’ll find evidence of the Anasazi who lived here until their mysterious disappearance around 1200 A.D. Petroglyphs, pictographs, and their granaries, some with intact corn cobs, are tucked high into the cliffs.

Later settlement of this area revolves around the Mormons, or Latter Day Saints (LDS). Their first prophet was Joseph Smith, Jr. and they lived in the Midwest, mostly Illinois, Missouri, Ohio, and Indiana, and were often persecuted for their religious beliefs. After Smith’s death in 1844, Brigham Young assumed leadership, but the LDS were attacked repeatedly by other settlers, and in 1846 they headed west, not knowing what dangers lay ahead. Two years later, many of them settled in the Salt Lake Valley. John Doyle Lee (who eventually had 19 wives and 67 children) continued, leading members into the areas surrounding what is now Page and founding numerous small settlements, where they raised cattle and farmed cooperatively. To make the area safe for their livestock, at Young’s suggestion, Lee supervised a hunt to rid the area of wolves, cougars, hawks, eagles, crows, bears, mink, and coyotes. Two teams of a hundred men agreed upon a system to determine the champion, and 14,000–15,000 animals were killed, with Lee himself accounting for 2,043 “skelps”. In 1856 Lee became an Indian Agent, assigned to help the Indians learn farming.

In early September 1857, an emigrant group from Arkansas camped at Mountain Meadows, a common resting place before the final desert crossing to California. As they had traveled through Utah, some members of the group had bragged that they had participated in slaughtering LDS members in Missouri, which didn’t exactly endear them to the locals, some of whom wanted revenge. The group also possessed a large number of cattle, which some of the local Indians wanted to steal. Over a period of days there were several skirmishes. Exactly what happened may never be known, but on September 11, it is thought Lee convinced the travelers to surrender their weapons in exchange for safe passage. The weapons and 17 small children were put in one wagon and sent ahead. Then the Mormons opened fire upon the men, while the Indians came out of ambush and dispatched the women and older children. 120 travelers were killed, leaving only the 17 youngest children to survive, taken in by local women.

For years, Lee moved from town to town, farming, building homes for his wives, and eking out a living. Rumors dogged him. Slowly, the laws of the United States were filtering in to the remote corners of Utah. Pressure was building to eradicate polygamy, and officials were looking for the perpetrators of the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

In 1871, Brigham Young ordered Lee to take two wives, leave the others, and build a ferry crossing over the Colorado River. He did this at the Colorado’s confluence with the Paria River, and this is the Lee’s Ferry of today, about 8 miles downstream from Page. (The river was initially called Pah Ria. Pah means water in Supai Indian languages. Think of Tonopah, Pahrump, etc.) The Grand Canyon officially begins below Lee’s Ferry.

Finally Lee was arrested and tried in 1874, where the defense declared Lee did not himself commit any murders, and was only acting on orders from the church. The trial ended with a hung jury. Lee was a model prisoner and eventually granted bail. His sons tried to get him to jump bail and go to Mexico, as did the church, but he stood trial again. This time many testified against him; perhaps there was a need for a scapegoat so others could move on. Lee was convicted, and never spoke in his own defense, despite hints of clemency from the Governor if he would implicate those above him. On March 23, 1877, Lee was taken to Mountain Meadows, blindfolded and seated upon his coffin, which he fell into as he was executed with 5 shots. You can see his grave today just east of Panguitch, off Hwy 89 between mile posts 130 & 131, if you decide to drive north to Bryce Canyon (see What to Do).

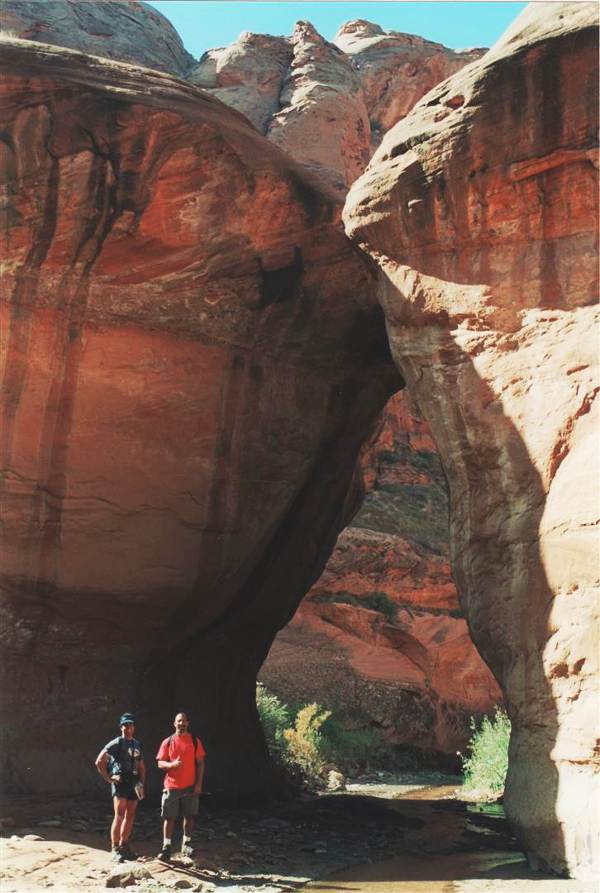

Another Mormon group attempting to establish a new settlement attempted a short cut in 1879 and was stopped 1,200 feet above the Colorado River for months until they cut a path down an incredibly steep cleft, lowering their wagons, women, and cattle, without a single casualty at Hole-In-the-Rock, which you can visit today from Lake Powell. If you climb to the top, you’ll find their original inscriptions, etched into the sandstone in 1879. They continued on to establish the town of Bluff, Utah.

In 1869, John Wesley Powell, a one-armed veteran of the civil war, led one of the most harrowing expeditions ever attempted. With nine men and four boats he departed Green River, Wyoming on May 24, following the Green River through Flaming Gorge to its confluence with the Colorado, and then all the way through the rapids of Cataract Canyon to a long stretch of calm water and magnificent rolling sandstone domes and alcoves, which he named Glen Canyon. Frequently stopping to explore and take measurements, Powell and his men reveled in the canyon’s splendor, naming many of the side canyons, including Music Temple Canyon, where they sang as in a church. From there it was on through the terrifying rapids of the Grand Canyon, and when they emerged at the Virgin River on August 30 (where the Lake Mead reservoir begins today), they had become the first to ride the mighty Colorado all the way through the Grand Canyon. Powell made another expedition two years later (stopping for supplies at Lee’s Ferry), then roamed the area with Mormon missionary Jacob Hamblin, meeting Indians of various tribes and documenting their languages and traditions, as well as the ecology and geology of the Colorado Plateau. He became the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey and reported to Congress, recommending that the land west of the 100th meridian not be heavily settled, as it was too dry for crops.

But the West was settled heavily, and the people demanded a reliable water supply. The Colorado River Compact, signed on November 24, 1922, split the allocation of Colorado River water into Upper and Lower Basins, and Hoover Dam was completed in 1935. Later, a dam was proposed for the upper basin which would have flooded Dinosaur National Monument. Another was proposed inside the Grand Canyon itself. The Sierra Club objected, controversy ensued, and eventually a compromise was reached, allowing one dam to be built that would flood Glen Canyon. Construction began in 1956, and the city of Page was created to house the workers, with land exchanged from the Navajos. With the dam’s gates slated to close in 1963, a last-ditch effort was begun in 1958 to document prehistoric art and ruins, as well as arches, alcoves, and other geologic wonders that would be obliterated by the water. It was conducted by Gregory Crampton of the University of Utah, and his book, Ghosts of Glen Canyon, is a must-read for those interested in the area and makes one wonder what Powell would have thought of the reservoir being named for him.

The dam generates enough electricity for about 650,000 people, but the Colorado River also brings an amazing 10,000 dump trucks-full of sediment to the reservoir every day. Meanwhile, the yearly water losses to evaporation and seepage could supply the entire state of Nevada. Between ongoing drought and sediment fill, eventually the dam will be rendered useless, but no one knows when. Loss of this sediment to the downstream Grand Canyon has altered the environment enough to endanger a number of native fish. Periodic large water releases have attempted to mitigate this problem by stirring up sediment downstream, but it remains to be seen whether this will be effective. Still, the reservoir attracts 3 million vacationers annually, the vast majority in summer, and supports the local economy.

The nearby Navajo Generating Station coal-fired power plant generates nearly twice the electricity of the dam, as well as 19.9 million tons of CO2 and 330 pounds of mercury yearly. An attempt was made to construct a coal mine and plant on the Kaiparowits Plateau, overlooking Lake Powell and across from Rainbow Bridge, but President Clinton’s 1996 creation of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM) finally laid that to rest, over the objection of many longtime residents. West of Page, the Vermilion Cliffs are the second “step” in the Grand Staircase, made up, like the other sandstones of the region, of deposited silt and petrified sand dunes. They owe their fantastic colors to alternate bands of red iron oxide, manganese, carbonates, and other minerals. The Vermilion Cliffs National Monument was designated in 2000.

What to Do

Winter is a magical time on the Colorado Plateau. Snow sprinkles the red cliffs like powdered sugar on a ginger cake. Daytime temps hover around 40°, completely comfortable for hiking if you wear polar fleece. Most days are sunny; winter storms are fleeting. Spring and fall are most popular for hiking, so you’ll have company. Highly recommended is Michael R. Kelsey’s Hiking and Exploring the Paria River, which has all the hikes described below and many more. Also recommended is Best Easy Day Hikes: Grand Staircase/Escalante and the Glen Canyon Region, by Ron Adkison.

The Wave and Toadstools

Visiting The Wave takes planning, but it’s more than worth the effort. Start with the BLM website, and then type Coyote Buttes into the Search Bar. You’ll find a wealth of information here. A $7 permit is required, but only 20 are issued for each day, ten online and ten as walk-ins. Online slots open up four months in advance, and often book immediately. If you don’t wish to book online, call (435) 688-3246.

The BLM staff will issue driving directions to the Wire Pass trailhead for your hike. The House Rocks Valley Road turnoff is about halfway between Page and Kanab, off Hwy 89 between mileposts 25 & 26, and you travel south on its dirt road for 8.5 miles, till you are near the Arizona border. The road can be impassable after rain, but you would have been notified of this the day before at the BLM office.

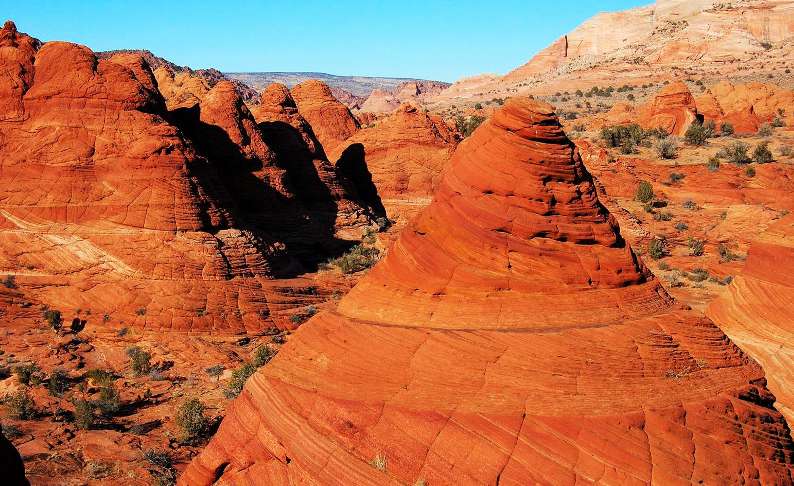

The BLM will also give you a map with photos of landmarks along your hike to The Wave, so you don’t get lost (there’s no trail in this Wilderness Area and you probably wouldn’t find it otherwise). We departed early and had the entire area to ourselves, but this was in mid-winter, and some years ago. It’s a pleasant 3-mile hike, first through a sandy wash, then over slickrock past colorful “teepees” of stacked sandstone. When you get to The Wave, walk around it, savoring the formations in the vicinity, and then approach from above—the colors and shapes will take your breath away.

Bring your camera! Lie on the rocks, feel the sun, and walk gently on the fragile surface. Although The Wave follows a natural fracture in the Navajo Sandstone that has been enlarged by water, these rounded bowls are shaped by wind, accelerated by a venturi effect. Look at those stripes up close—red, orange, yellow, white, and purple—the rhythmic and cyclical bands were formed by alternating grainflow, reflecting seasonal changes in sand dune migration and chemical reactions due to water or lack of it. The initial reddening is caused by grain-coatings of iron oxides (e.g., hematite); a bleaching event by reducing fluids; a secondary introduction of iron evidenced by darker rings; and a final overprinting of a yellow banding.

On the way back from The Wave, we wandered northeast, past more teepees and stood above the Buckskin Gulch narrows. One of the premier slot canyons, its walls are 100–200 feet tall and you can sometimes touch both sides of the canyon with your hands. I looked down and couldn’t see the bottom. This hike is also accessible from the same Wire Pass trailhead, and doesn’t require a permit unless you want to hike farther and stay overnight (you can actually hike all the way down to Lee’s Ferry), but I wouldn’t want to do this in winter—too cold. Go to the website above and click Paria Canyon. Never enter any slot canyon if there is any chance of rain.

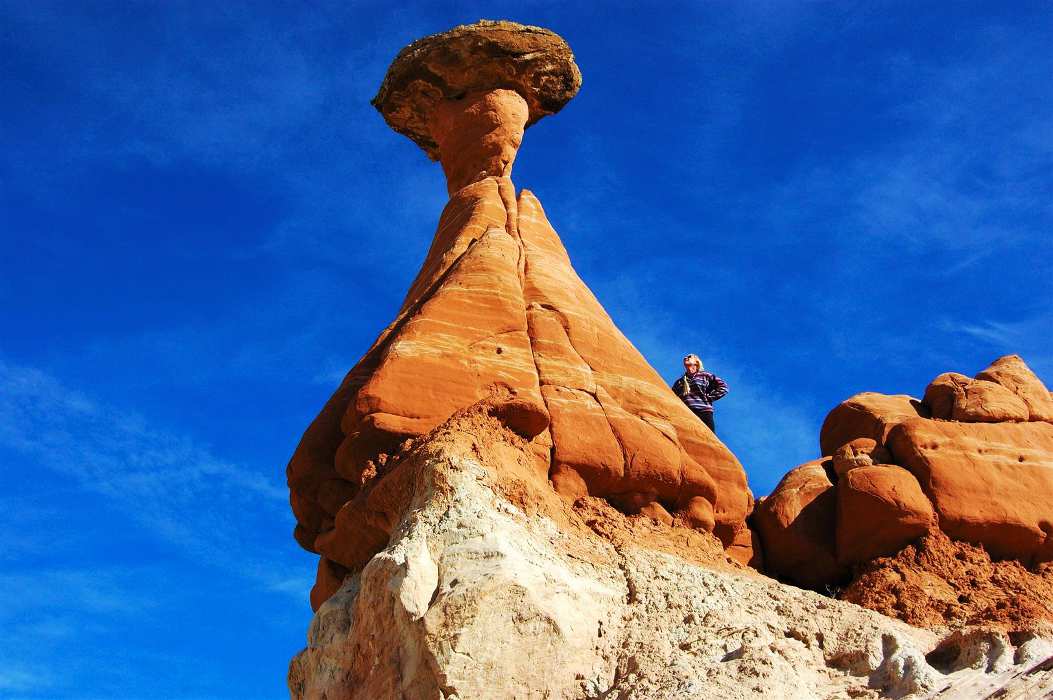

A wonderful surprise awaits you on the drive back from Kanab. On the north side of Hwy 89 between mile markers 20 & 19, you’ll see a parking lot and trailhead. A well-worn trail leads north into the GSENM; after less than a mile you’ll see an enormous red toadstool, or hoodoo. From here just wander up onto the plateau; you’ll be standing on hard clay. There’s no vegetation, just hundreds of these toadstools. Most have a white “stem” of soft Entrada sandstone, topped by a dark Dakota sandstone boulder. They were formed over eons as the Dakota rock prevented the soft Entrada below from being eroded by rain. Look around both east and west; the longer you stay, the more you’ll see, all shapes and sizes—it’s unforgettable. I had the strangest sensation of being on another planet. There wasn’t a sound or another person around.

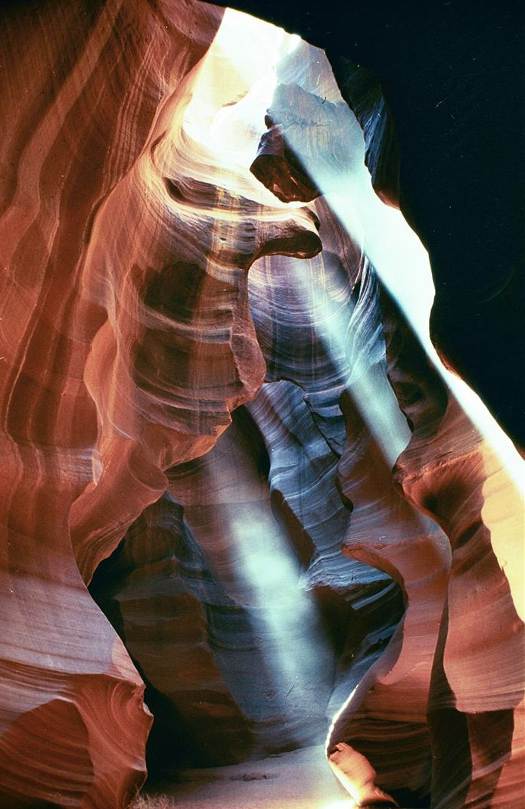

Upper Antelope Canyon

Few desert visitors ever see a real flash flood, so perhaps the best way to understand what happens is to stand inside Upper Antelope Canyon, the most-photographed slot canyon in the world. Between March 15 and October 7, a shaft of sunlight can strike the ground inside, a sharp contrast to the subtle shading on the sensuously twisted Navajo sandstone walls. But winter light is equally lovely, and without the crowds. Located near Page inside the Navajo Reservation, you need a guide, and there’s none better than Carolene Ekis, who has carried on her late husband’s Roger Ekis’ Antelope Canyon Tours. The 90-min tour departs from their Page office in a huge 4WD truck, rumbling up a sandy wash to a sandstone cliff with a large crack in it. Step inside—it’s easy walking—and look up. Carolene knows all the best places for you to aim your camera, and will help you with your settings. This serene slot canyon has been formed through unimaginably violent flash flooding, where a torrent of water up to 60 feet high forces itself through the rocks any way it can, sometimes washing away 15 feet of sand, which slowly builds up again during gentle rains. The rock actually mimics the flow of rushing water. Book tours ahead, $16–$34 adults $32, children 8–12 $20, tours depart 7, 8, 9:30, and 11:30 a.m., 22 S. Lake Powell Blvd., (866) 645-9102 or (928) 645-9102, //www.antelopecanyon.com/.

If you’d like to see more, visit Lower Antelope Canyon as well. Shallower and narrower than Upper Antelope, entrance and exit require climbing stairs and the footing is less even. In 1997, 11 tourists died here when a flash flood tore through, hence the requirement now that all visitors be escorted by licensed guides, who are very cognizant of weather conditions. Ken’s Tours, 8 a.m.–5 p.m., (928) 606-2168, //lowerantelope.com/.

Cottonwood Canyon

An adventurous driving/hiking day can be had up Cottonwood Canyon. From Page, drive west on Hwy 89 and turn north on Cottonwood Canyon Road, between mileposts 17 & 18. You cannot drive on this road when it is wet! The road will go from gravel to shale/clay, and under no circumstances should you attempt to drive the clay road if it’s wet, even in a 4WD—you’ll get stuck, and in winter, the next car may not come for days. An interesting geologic formation, the Cockscomb, eventually parallels the road’s east side, its yellow rocks pushed up at a crazy angle. At 14.6 miles from Hwy 89, you’ll come to Hackberry Canyon on your left, a wonderful hike. The creek is perhaps an inch or two deep, semi-frozen in winter. Your footsteps crunching the ice will be the only sounds in the crisp, clean air. Go as long as you like and then turn around, mindful of short winter days. You can explore the slot canyon of Upper Cottonwood Wash Narrows by driving another 11.3 miles up Cottonwood Wash to a parking area on the left near some red and white rocks. Scramble down into the drainage, explore a little to the north, where it’s very narrow, then walk south inside the drainage for about a mile. Exit to the east, back up to the road, and walk to your car. If you still have time, Grosvenor Arch is just another four miles north, on the east side of the road.

If you want a 2-day or more driving trip, from Grosvenor Arch it’s about 10 miles north to paved road, where you can make a big counterclockwise loop through the Kodachrome Basin, Cannonville, east on Hwy 12 to Bryce Canyon National Park, visit Lee’s Grave in Panguitch, then back south on Hwy 89 to Kanab, and from there east to Page. Get some good maps. The total unpaved mileage of Cottonwood Canyon Road is about 45 miles.

California condor viewing can be done in the Vermilion Cliffs, where they have been released since 1996: contact //peregrinefund.org/home-feature/california-condor to find out when they will release birds, or call 208-362-3716.

Horseshoe Bend

Another must-see while in the area is Horseshoe Bend, where the Colorado River below the dam meanders around a large butte. Drive four miles south on Hwy 89 to a blacktop road leading west, just south of mile marker 545. A short walk leads you to the rim and—wow!—a 500-foot unfenced drop-off, with aqua-colored water circling the red sandstone. Mid-day is best for photos here.

Glen Canyon Dam

Since you’re near the dam, it’s a good time to stop by the Carl Hayden Visitor Center and perhaps take a Glen Canyon Dam Tour. 45-minute tours take you inside the dam; free, 8 a.m.–4 p.m. winter, (928) 608-6072, www.nps.gov/glca/planyourvisit/visitorcenters.htm. The visitor’s center has geology displays and a nice selection of books. Join the Glen Canyon Natural History Association and get their beautiful magazine, Sojourns, as well as discounts and news about their interesting guest speakers, www.glencanyonnha.org.

The John Wesley Powell Memorial Museum

The John Wesley Powell Memorial Museum, in downtown Page, displays Indian and pioneer artifacts. It also explains Colorado Plateau geology and the construction of Page and the Glen Canyon Dam. Call them and they’ll send you a travel pack before your trip, open Mon–Fri 9 a.m.–5 p.m., Sat 9 a.m.–1 p.m., 6 N. Lake Powell Blvd., (928) 645-9496, www.powellmuseum.org.

Lake Powell

If you’d like to get out on the reservoir but don’t want to rent a houseboat, Aramark has a variety of cruises, from dinner cruises, to canyon visits to Rainbow Bridge, the largest natural bridge in the world at 290 feet high, and spanning 275 feet across Aztec Creek. It’s a one-mile walk to the bridge. Cruises depart year-round from Wahweap Marina, schedules vary, www.lakepowell.com/tours.

Kayak Powell offers kayak tours, kayak rentals, hiking tours, Jeep tours, and shuttle service March–October, with airport pickup and single or multi-day trips, if you’d rather not plan your own, (928) 660-0778, www.kayakpowell.com.

A completely different way to launch (literally) a weeklong vacation from Page is by houseboat. Summer’s heat makes Powell a paradise for fishing, waterskiing, swimming, and jet skiing. Don’t let the talk of drought fool you—this reservoir is so enormous you’ll never run out of room for wet fun. Summer brings crowds, however, so if it’s peace and hiking you crave, avoid summer. The absolute best weather is usually about Sept 20–Oct 20, around 72° and little wind, yet warm enough at night to sleep out on the top deck and watch satellites and shooting stars. April 1–May 15 is excellent too, with longer days and wildflowers, but more wind. We rang in the new millennium on our houseboat and had excellent, brisk weather.

Prolonged drought has actually vastly improved Lake Powell. In 2000, when the reservoir was full, it was essentially a giant, beautiful, sandstone bathtub, with little wildlife above the water. In 2002, water levels fell and hikes up the side canyons were long slogs through smelly muck. Since then, flash floods have scoured the canyons to bedrock as the dropping water levels exposed many miles of side canyons with their fascinating geology, now home to 25-ft cottonwoods, willow, beaver, deer, and birdlife galore, while the main channel still has all the room you need for boating and skiing. Explore narrow slots like Twilight, Mountain Sheep, or West Canyons, or climb onto a slickrock bench and see the water below. Definitely buy Michael R. Kelsey’s book, Boater’s Guide to Lake Powell for maps and descriptions of every hike in every canyon, buy a Stan Jones lake map at the marina, and bring binoculars so you can see the buoys and not get lost on the reservoir.

Page is near both Wahweap and Antelope Point Marinas, but Antelope is far newer and nicer, with better boats. After free airport pickup, they’ll deliver you and your bags to your boat. There’s a floating restaurant, a gift shop full of souvenirs, clothing, and books, and a grocery store for last-minute refrigerated items like milk and ice cream, or anything else you forgot, like sunscreen. Arriving early? From about Sept 4–May 20, you have the option of spending the night in the marina on a rental boat, complete with breakfast, $250. 2009 houseboat rentals range from $4,000–$14,795, depending on size of boat, length of trip, and season. Large boats can sleep many people, lowering the cost per person. Find a great parking spot for the houseboat and make day trips in smaller craft, which save gas and can maneuver into the narrower side canyons. Kayaks, jet skis, and ski boats can be rented as well, and stored on or towed behind the houseboat, (800) 255-5561 or (928) 645-5900, www.antelopepointlakepowell.com.

You can save money in the long run by buying a share in a custom houseboat. Take advantage of all Antelope’s services, including motorboat storage. Sunrise Peak specializes in Lake Powell, with boats at Antelope Point from $10,000 a share and up. You pay an average annual fee plus launch and retrieval but when you factor in depreciation, if you love houseboating and do it regularly, you come out way ahead, (801) 424-2628, www.sunrisepeak.com.

The secret to a successful houseboat trip is planning.

How full is your plane going to be? For instance, when we took our 3 children in our 6-seat Cessna 210, weight and space restrictions made it necessary to send certain items ahead by UPS, and pick them up at the marina. These items included all the non-refrigerated foods, towels, sheets, and other items (more details below). Box your items securely, and address them this way:

Antelope Point Marina

Houseboat Rentals

Navajo Route 22B

Page, AZ 86040

Put your name and reservation date on the boxes as well, and make sure you speak with personnel at the marina so they know you will be sending some of your gear and will hold it for you—double-check the address and procedures with them. Find out where your boxes will be stored, and send them early enough so they get there before you do.

When we made trips with just the two of us, there was plenty of space and useful load left in the aircraft to take everything with us.

Several weeks before your trip, start making lists.

1) Items to send UPS (if necessary).

2) Items to pack.

3) Frozen food.

4) Refrigerated food.

5) Items to buy at the marina store.

Every single thing you are going to bring goes on one of those lists. (I save the old ones, and make new lists for each trip from them; then I am less likely to forget something.) Of course you have to make grocery lists or other lists for everything you need to buy for your trip, as well. When it comes time to pack, check the item off your list, once it is packed.

Items to Pack (and/or UPS) – would include all clothes for everybody. Remember visors, hats, sunglasses, bathing suits, good hiking socks and shoes, mittens, activewear (layers), depending on season. You need to bring your own towels, sheets, pillows, blankets, and I suggest sleeping bags if you’d like to sleep on the roof of the houseboat, which is lovely in good weather. The nice thing about a houseboat is you can have it all. Bring wine if you want, or boxes of cereal—whatever you like to eat. Remember toiletries, medications, etc., extra ziploc bags, books, games, CDs, DVDs, snacks, paper towels, and Windex. I like those canned protein drinks for hikes because you get both liquids and energy. Bring daypacks and refillable beverage containers, trail mix, etc. You can backpack and camp if you want, so then you may want to bring larger packs, a tent, and camping supplies. Don’t ship valuable items like cameras; you want that in the plane anyway.

Frozen Food – I plan a menu for each day, all meals. So then I total up what I need, for instance how many chicken breasts, how many steaks, etc. The houseboats all have BBQs and nothing tastes better outdoors after a hard day’s playing. They also have full-size ovens, stoves, and microwaves. You can bring all the usual foods your kids like to eat, so they’ll be comfortable. Think about what you want for lunch: I pick up good turkey meat at the deli and bread for sandwiches, as well as chicken breasts to BBQ and serve cold later. With regard to all the meat, I trim and/or season steaks at home and put them in separate ziploc bags for each day. Same with the chicken breasts; I marinate them and put them in ziploc. I have an Igloo cooler, and put all the meat in that. Since it isn’t frozen yet, you can cram a lot of meat in there, maybe frozen veggies too. Fill it up, keep the top open, and put the whole thing in the freezer. Give it at least 24 hours to freeze like a big brick. When you leave your house, take it out of the freezer and it should still be frozen when you get to the houseboat and transfer it to that freezer. Then each night, just take tomorrow’s food out to defrost in the refrigerator all the next day.

Refrigerated Food – This would be things like lettuce, cheese, deli meats, salad dressing, or whatever you have planned. Pack another Igloo and leave it in the refrigerator, then throw in some plastic ice bricks before you leave, and it should be fine till you get to the houseboat.

Buy at the Marina Store – We go through a lot of milk, and since it’s heavy, I buy it at the marina store. Same with eggs, ice cream, sodas, and any other goodies you might see there. If you like, you can buy firewood at the store for campfires (don’t forget the marshmallows!)

One Last List – As the time to depart your home draws near, there are certain things you don’t want to forget, so put them on a list. Like: the refrigerated food, the frozen food, your kid’s retainer, cancel the newspaper, arrange for your mail, lock the windows, charge the camera battery (and bring the charger), whatever you want. Then check those items off as you do them, and leave for your trip with peace of mind.

Houseboat Tips:

Whether you rent a houseboat or are using your share on a houseboat you own, you will be checked on and off by staff to make sure everything you need is there, and to assess any damage. As you go around with the staff person, make sure the propane tanks are full, the prop isn’t dinged, and ASK if there is anything you don’t understand, like how to turn on the generator, or the lake water vs. the potable water, for instance.

Ask about the radio; 16 should be emergency channel, and make sure everyone knows it. What channel does Antelope Marina use?

If you have the marina staff pilot the boat in and out of the marina, you won’t be liable if the houseboat hits anything there. Twin-engine experience helps in piloting. If you are going to tow another small boat, first lash it to one side of the houseboat. Outside the breakwater, put the houseboat’s engines in neutral and then reposition the tow rope to the back, making sure not to tangle it in the props. Ensure that the towed boat’s engine is straight so it pulls evenly, and partially raise its prop to reduce drag. Go back and check on the little boat once in a while—our line broke once, and it took an hour to find the boat! You did put the plug in, right?

It’s best not to run the generator when you are underway. Sand can get sucked into it.

Once underway, you can let kids pilot the boat (under close adult supervision). Stay to the center of the channel.

The NOAA weather channel on the radio is very useful, so listen daily. Weather here can change quickly.

Mooring:

Wind is the enemy when mooring. If you know from the radio weather that a windstorm is due, get moored before it begins. This is the time for teamwork. First, look for a place sheltered from wind and from large waves that can develop in the open channel, both from boat wakes and windstorms. Don’t wait too late in the day, or it may get dark before you find the right spot. Binoculars help here as well. Once you choose your site, stop in deeper water (engines running but in neutral), haul in the boat being towed (if there is one) and lash it to the appropriate side of the houseboat (away from rocks)—watch that the line doesn’t get tangled in the props. This is not the time for the kids to be clamoring for food. (Think sterile cockpit on takeoff and landing.)

Most houseboats allow piloting from the top as well as the helm inside, and some people find they can see better from on top. Definitely install people on top to watch for rocks so you don’t ding the props as you get to shallow waters, and hold onto the railings. When you hit the beach, use power to push the boat up onto the sand, but not so far you can’t get away later. It’s best to leave the engines running and have someone on top monitor the boat, which should be perpendicular to the beach. If wind begins to push it to one side before it is anchored, this can be countered with differential engine power. Now is the time to hustle out with the anchors, securing lines from all four corners.

Learn how to tie good knots, quickly.

The sandstone dissolves into sand, which is everywhere. That and the ropes are tough on hands; this is not the place for fancy jewelry.

Learn how to moor the houseboat with four anchors. At least one windstorm comes up every trip I have taken, and the lake whips up 5-foot waves. The houseboat is like a giant sail. The boat can come loose even if tied to huge boulders. Such emergencies are all part of the “fun” and you can laugh later—sort of like surviving nasty turbulence or other flying challenges!

When departing, do all in reverse. Start and let engines warm before untying the houseboat. After you get into deep water, stop (engines running but in neutral) and move small boat to the back (if you are towing one), taking care not to tangle the line in the props.

Safety & Other Tips:

Never let people swim when any generators or engines are running—there are horrific accidents here yearly—and no jumping off cliffs into the water.

Don’t ever let anyone take the little boat, or Jet Ski, without them really knowing how to operate it. If the engine quits, do they understand the choke? This reservoir is so huge, finding a lost person can be like finding one ant in your backyard. Yes, this happened to me. I got stuck in a cove at dusk, with no shoes, food or water, and wearing only a bathing suit, after having jumped into the small boat to go ahead to look for a place to park overnight. The engine quit, and I couldn’t get it started again, so I stopped trying, not wanting to deplete the battery. My husband couldn’t find me. Hours later I remembered the emergency channel and Maydayed, which he heard. We reunited around midnight. I knew I would be OK, even if I had to spend the night alone, but he literally didn’t know if I was even alive. And what if it was your kid? (Actually, they should be supervised, and it’s illegal to let minors boat alone anyway.)

Keep track of the buoys and use the Stan Jones map so you don’t get lost.

Check out Secret Canyon if you get that far uplake—it’s a narrow twisting channel and only a small boat will fit—quintessential Lake Powell.

You can get fuel and groceries at Dangling Rope Marina.

From Wahweap or Antelope Point, most boaters stay in Padre Bay, but I find the reservoir far more interesting farther uplake.

Cell phones should work in Page; farther up on the reservoir they only work if you are within sight of Navajo Mountain.

Hiking Tips:

Twilight, West, Mountain Sheep, Cathedral, and Cascade canyons are deep, fascinating slot canyons. The Escalante, and Cathedral in the Desert, are beautiful. Cha Canyon, in the San Juan, has tons of easy-to-find petroglyphs.

I never saw a rattlesnake, but my husband did.

Bring plenty of water!

Step carefully; if you sprain an ankle, there is no one to come and get you. When we go, in October or April, we never see anyone on our hikes. That’s what’s so nice about hiking Glen Canyon—boaters generally stay on/in the water, and are scarce between October and May, and hikers either scorn the reservoir or cannot access its canyons from land-based trailheads, as many canyons end in steep drop-offs.

When you read Kelsey’s book (Boater’s Guide to Lake Powell) for hikes, plan on almost double his allotted time unless you are a super-fast hiker. The guy must literally run his hikes.

Note the high water marks and think how nice it is that where you are is no longer under water. The farther away from the reservoir you get, the more natural the plant life. Don’t “bust the crust”, the cryptobiotic soil you find away from trails, which takes decades to recover and prevents erosion.

Usually you hike up a canyon, then back. Start early and pay attention to time, so you know when you must turn back.

Where to Stay

Almost all Lake Powell’s 3 million annual visitors arrive in summer, so hotels fill up then, but late Sept–May things are quiet. To get to town from the airport, turn right onto 11th Ave., left onto N. Navajo, and right onto Lake Powell Blvd. No problem either if you’d like to attend church on Sunday—just go to the “Holy Curve” on Lake Powell Blvd, with 10 in a row. During Page’s construction, churches were offered free land, and there are 14 in town altogether.

The Marriott Courtyard is at the western end of Page. Head west through downtown, and after you begin your descent toward the dam, you’ll see it on the left. The Marriott is surrounded by the Lake Powell National Championship 18-hole golf course, and has a view over the reservoir, Marble Canyon (below the dam), the bridge, and GSENM in the distance. Its reddish adobe exterior mirrors the sandstone cliffs, and its 153 spacious, non-smoking rooms have free wireless hi-speed internet, refrigerators, coffee makers, and HBO. Pepper’s southwestern restaurant and cantina is closed for lunch and dinner Nov–March, but the breakfast buffet, is open year-round; the pool is seasonal as well, 600 Clubhouse Dr., (928) 645-5000, www.marriott.com/hotels/travel/pgacy-courtyard-page/.

The Lake Powell Resort overlooks Wahweap Marina above the dam. Drive through Page, cross the bridge, go down a hill, and the entrance is on the right. Many rooms or suites have lake views. The resort is a buzz of activity during summer, but ghostly quiet Nov–May, when many facilities close, 100 Lakeshore Dr., (888) 896-3829 or (928) 645-2433, //www.lakepowell.com/accommodations/wahweap-resort-accommodations.aspx.

We actually preferred the Days Inn, just southwest of town off Hwy 89. It was new, with free continental breakfast, internet, and available Jacuzzi suites. We took advantage of the nearby self-drive-thru carwash to remove all traces of our off-road escapades to The Wave and Cottonwood Canyon, rooms from $79, 961 N. Hwy 89, (928) 645-2800, www.daysinn.com.

Where to Eat

Skip the subpar steakhouses and head to the Dam Plaza, at Navajo & Lake Powell, for three establishments under the same management. You can get a little of everything at the Dam Bar & Grille, whether you’d like to sit at a large bar and watch sports, dine below a tall façade of the dam, or cuddle up in a quiet booth beside a fine painting of local landscapes. The menu offers an array of steaks, pasta, seafood, salads, and burgers. We enjoyed the Southwestern Cobb Salad and Black & Bleu Burger one night and the herb-crusted King Salmon draped in a wild blackberry ginger sauce the another night. If you’re into Japanese, ask the hostess to take you through the back door into the Blue Buddha, with stylish orange seats, a long turquoise wall with a sunk-in aquarium, and a lounge atmosphere. Blue offers espresso, lattes, and a bakery by day, and tapas by night, www.damplaza.com.

Spirits are high at Fiesta Mexicana, where cheerful waiters greet you with Amigo and the walls are covered with brightly colored paintings. Standard but tasty Mexican fare such as tostadas, fajitas, carne asada, seafood, chicken, combos, and big margaritas, 125 S Lake Powell Blvd., (928) 645-4082, //www.fiestamexicanarestaurants.com/.

Transportation

Antelope Point Marina houseboats and the tour companies offer free airport pickup, but land-based exploration outside Page requires a rental car, with 4WD recommended for off-road travel. Avis has vehicles at the FBO, (928) 645-2024.

In Conclusion

Surrounded by multiple National Parks, Monuments, and a Recreation Area, Page Airport could be your ground zero for enough adventures to fill a lifetime. You can find peace and beauty in every quiet sandstone nook, where water has carved its way through half a billion years’ worth of layered deposits. Or enjoy today’s technology as you cavort on the reservoir with friends and family. You can even do both by hiking from your houseboat. With so many dramatic landscapes to see, even from the air, it’s a doubly rewarding pilot’s destination.

(Photos by Crista and Fred Worthy)

Leave a Reply