First Flight: Gustave Whitehead

Welcome to part three of the First Flight series. In case you missed them, or want a refresher, here are part one and part two.

Of all the people with claims to have flown before the Wright Brothers, perhaps the most controversial is Gustave Whitehead (an Americanized version of his German name Weisskopf), a German immigrant with an burning passion and talent for all things aviation. Born in 1874, Whitehead’s parents died while he was still young (1886 and 1887), and he began training as a mechanic in Hamburg in as a mechanic in 1888, when he was fourteen. He then spent a year as part of a crew on a sailing ship, returning to Germany in 1889. He next moved to Brazil with another family, spent a few more years at sea, and finally immigrated to the US in 1893. He was hired by a New York toy manufacturer to build kites and model gliders.

In 1896, he was contracted by the Boston Aeronautical Society, along with Albert BC Horn, to build a glider and an ornithopter. Whitehead was able to make a few successful low and short flights with the glider, but could not get the ornithopter to fly. Later that year, Samuel Cabot (the founding member of the society) hired Gustave Whitehead and James Cromwell (a carpenter) to build a replica Lilienthal glider. Cabot and the society ran several flight tests using this glider, but none were successful.

Gustave Whitehead Claims Successful Powered Flight

Between 1899 and 1903, Whitehead claimed to have made a successful powered flight at least five times. The first of these flights was said to have taken place in either April or May of 1899. Whitehead and Louis Davarich, a friend, said they made a successful powered flight of half a mile in a monoplane powered by a steam engine. Whitehead said he controlled the aircraft through means of shifting his body weight, something that many critics claim wouldn’t have been possible with the size and weight of an aircraft of that type. Davarich estimated they flew at a height of roughly 25 feet (7.6 m) over Pittsburgh’s Schenley Park.

The flight ended when they crashed into a brick building, severely scalding Davarich who was stoking the engine at the time of impact. Davarich spent several weeks in the hospital, and Whitehead was reportedly banned by the police from engaging in any more flights in Pittsburgh. The only evidence to support this flight was an affidavit given by Davarich in 1934. Given the lack of evidence and questionable details, many aviation historians don’t believe this flight happened.

Gustave Whitehead and Number 21

The second occasion on which Gustave Whitehead claimed powered flight, 14 August 1901, is the most notorious and well-known, due to an accompanying ‘eyewitness’ report. The monoplane Number 211 served as the aircraft for this second powered flight. On 26 July 1901, Whitehead shared some details with the Minneapolis Journal on two unmanned test flights he’d made earlier that year in May. For the first flight, the aircraft was loaded with 220 pounds (100 kg) of sand as ballast, and was able to fly at a height of roughly 40 feet (12.2 m) for an estimated 659 feet (201 m). The second flight produced even more promising results, with a flight of 2,641 feet (805 m). The plane covered this distance in 90 seconds, before crashing into a tree. Whitehead did not disclose the location of the test flights, saying he’d rather keep the location secret to avoid drawing a crowd.

Finally, on 14 August 1901, Whitehead was ready to try a manned flight of Number 21. The test was to take place in Fairfield, Connecticut, and the Bridgeport Herald would be sending someone out to write an eyewitness report of the flight. This report was published on 18 August 1901, in the form of an unsigned article. Though the author of the report has never been definitively identified, it is widely believed that the report was written by Richard ‘Dick’ Howell, the sports editor for the Bridgeport Herald.

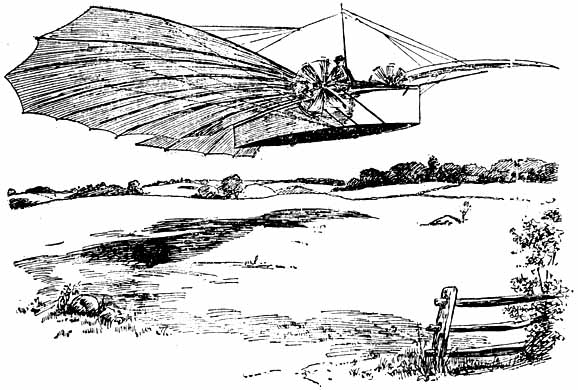

According to the report, Gustave Whitehead piloted Number 21 in a controlled flight for roughly half a mile, at a height of 50 feet (15 m), and was able to land safely. The report was published along with a drawing (also believed to be by Howell) depicting Number 21 in flight. The drawing is said to be based off a photograph, but no actual photographs of this flight were ever provided, or have ever been found. The report revealed several other interesting details.

First, in addition to the Herald’s eyewitness, two other eyewitnesses were named: Andrew Cellie, and James Dickie. Second, Whitehead drove Number 21 to the test site. According to the report, with the wings folded in, the monoplane functioned much like a car. It is said to have achieved speeds of 30 mph (48 kph) over the uneven road, and according to the report:

“There seems no doubt that the machine can reel off forty miles an hour and not exert the engine to its fullest capacity.”

Third, the report says Whitehead successfully test flew Number 21 unmanned, using sand as ballast and long tether ropes, before trying manned flight. Fourth, the report relates an incident of Whitehead almost flying into some trees at the beginning of the flight. Whitehead was quoted as saying:

“I knew that I could not clear them by rising higher, and also that I had no means of steering around them by using the machinery.”

And, according to the report, Whitehead devised a solution to his problem in the air:

“He simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other. This careened the ship to one side. She turned her nose away from the clump of sprouts when within fifty yards of them and took her course around them as prettily as a yacht on the sea avoids a bar. The ability to control the air ship in this manner appeared to give Whitehead confidence, for he was seen to take time to look at the landscape about him. He looked back and waved his hand exclaiming, ‘I’ve got it at last.’”

Finally, according to the report, as Whitehead neared the end of the field, he turned off the motor and landed Number 21 “so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least.”2

Shortly after publication, the New York Herald, Boston Transcript, and The Washington Times all ran a reprint of the article. Soon, it was being featured or mentioned in newspapers around the world. On 21 September 1901, Collier’s Weekly featured Whitehead and his flying machine, referencing the successful flight of half a mile witnessed in the article. A couple moths later, The Evening World featured a story on Whitehead and his accomplishments, quoting him as saying “Within a year people will be buying airships as freely as they are buying automobiles today and the sky will be dotted with figures skimming the air.” And in December, the Cocino Sun called Gustave Whitehead the ‘inventor of the flying machine.’

Gustave Whitehead and Number 22

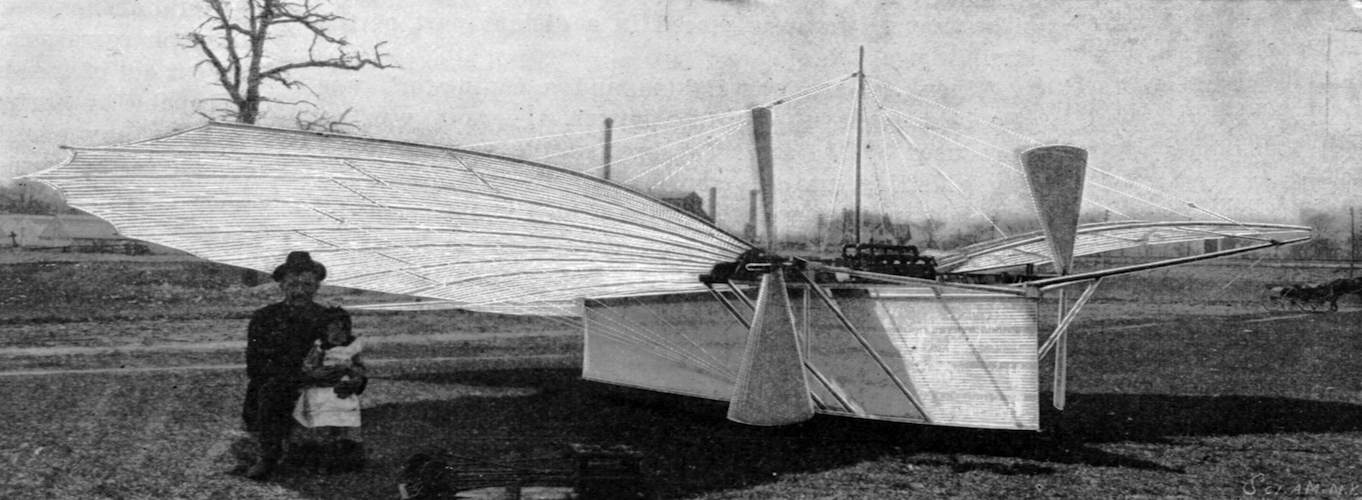

Gustave Whitehead claimed another pair of successful flights in 1902, these ones even more spectacular than his previous flights. He flew aircraft Number 22 for these flights, and this aircraft featured some changes from 21. First, Number 22 had a new engine. It was a five-cylinder, 40 hp kerosene engine of Whitehead’s own design, versus Number 21‘s 20 hp engine. At 16 feet long (4.9 m), Number 22’s frame was constructed mostly from steel and aluminum rather than bamboo. Details of the flights were provided in a pair of letters that Whitehead sent to American Inventor magazine.

The flights took place over Long Island Sound, the first covering a distance of 2 miles (3.2 km) and the second covering a distance of 7 miles (11.2 km). The plane reached heights of 200 feet (61 m), and owing to a boat-like fuselage, was able to be safely landed in the water near the shore. Whitehead said steering was achieved through varying the speed of the aircraft’s two propellers and use of a rudder. It was these techniques that allowed him such a lengthy second flight.

Whitehead, in his letters, expressed a great sense of achievement: “… as I successfully returned to my starting place with a machine hitherto untried and heavier than air, I consider the trip quite a success. To my knowledge it is the first of its kind. This matter has so far never been published.” He claimed photographs had been taken of Number 22‘s flights, but they did not turn out due to the rainy and cloudy weather. He told American Inventor “This coming Spring I will have photographs made of Machine No. 22 in the air.” Excited by this prospect, the magazine replied that they and their readers would “await with interest the promised photographs of the machine in the air.” However, Whitehead never contacted them again, and never provided photographs to anyone of Number 22 in flight.

Gustave Whitehead and Powered Glider Flights

And finally, in 1903, Gustave Whitehead claimed to have made several successful glider flights. They were detailed in article that ran in Scientific American on 19 Septmeber 1903. Whitehead, piloting a triplane glider, was towed against the wind by an assistant, using ropes. The glider had a 54 pound (24 kg) 12 hp engine that ran a two blade propeller 4.5 feet (1.4 m) in diameter. The propeller was mounted to the engine’s crankshaft in a tractor configuration, which meant that it pulled the aircraft forward rather than pushed it from behind.

“By running with the machine against the wind after the motor had been started, the aeroplane was made to skim along above the ground at heights of from 3 to 16 feet for a distance, without the operator touching, of about 350 yards. It was possible to have traveled a much longer distance, without the operator touching terra firma, but for the operator’s desire not to get too far above it. Although the motor was not developing its full power, owing to the speed not exceeding 1,000 R.P.M., it developed sufficient to move the machine against the wind.”

Gustave Whitehead’s Fame Dies Down

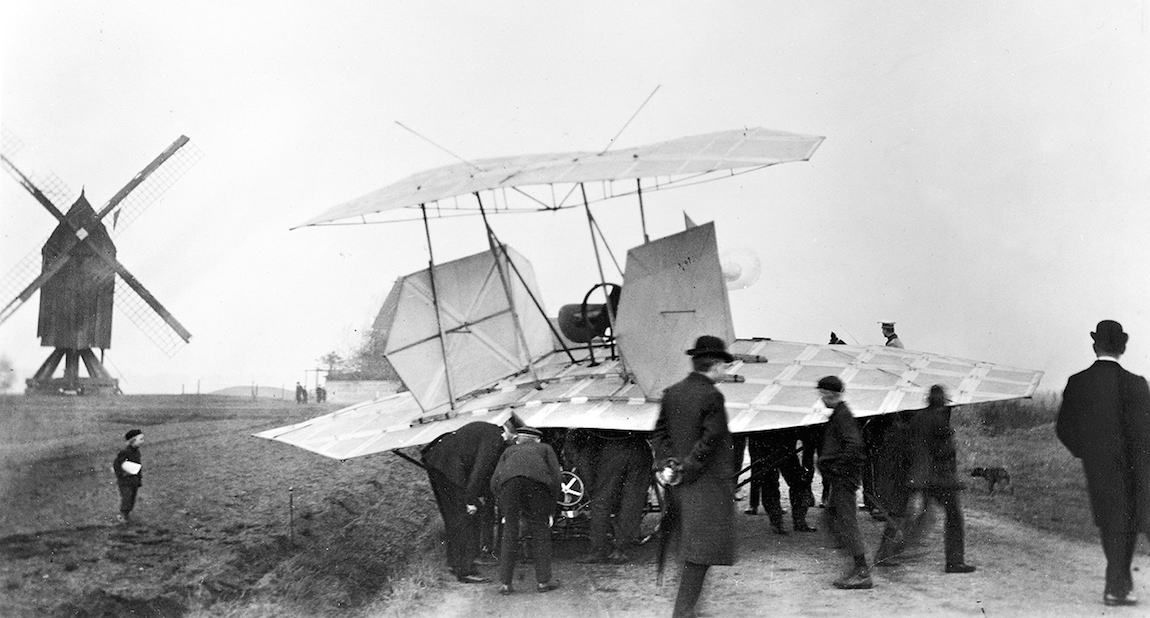

Though his flights generated a lot of initial excitement and press, Gustave Whitehead’s inability to supply photographs of the flights, or other conclusive evidence, led to most people moving on. Whitehead, it seems, came to be viewed as a dreamer and storyteller. Whitehead built his last three aircraft in 1908. He stopped building, as did many others, when the Wright Brothers obtained injunctions against other heavier than air aircraft manufacturing to protect their patents. To continue flying, aviators were required to purchase a ridiculously expensive Wright License (over $25,000) or purchase an aircraft manufactured by the Wright Brothers. Whitehead did continue to design aircraft, moving instead to building helicopters, which did not violate the Wright Brothers injunctions.

As with his aircraft, there are reports that some of his helicopters achieved some form of flight, but no photographs or evidence exits of these flights. And though the quality and success of his many aircraft was questioned, his engines were apparently much more successful. According to British magazine Air Enthusiast, “Weisskopf’s ability and mechanical skill could have made him a wealthy man at a time when there was an ever-increasing demand for lightweight engines, but he was far more interested in flying.” And though Whitehead never achieved great wealth from his engines, they were widely admired and used.

His slide into obscurity was briefly arrested in 1913 when Glenn Curtiss referenced his first flight claims during the Patent War with the Wright Brothers, but the courts found against Whitehead due to a lack of evidence. A year or two later, Whitehead lost an eye in a factory accident, also suffering a severe blow to the chest that is thought to have contributed to an increasing number of angina attacks. He recovered enough to go back to work, and in order to support his family, branched out his research. He invented a breaking safety device for railcars, and an automatic concrete laying machine, but neither invention brought in money. Whitehead eventually started working in a factory and taking on more engine repair jobs.

On 10 October 1927, he died of a heart attack. He was attempting to lift an engine out of an automobile he was repairing when it happened. As he suffered the attack, Whitehead stumbled onto his front porch, then into his house, and finally fell over dead.

Gustave Whitehead Supporters Keep His Legacy Alive

And that’s where Gustave Whitehead’s story might have ended, were it not for Stella Randolph and Harvey Phillips. Randolph, a journalist, and Phillips, a connoisseur of aviation history, co-wrote and published an article in Popular Aviation in 1935, with the intriguing title “Did Whitehead Precede Wright In World’s First Powered Flight?”

Randolph and Phillips article painted the portrait of a long-suffering, hard working man sadly passed over for the credit he deserved. Though not accusatory or defamatory of Wright Brothers or other early aviators, it definitely came down on Whitehead’s side. It mentioned a variety of people who claimed to have witnessed Whitehead’s flights, and though it didn’t mention the Bridgeport Herald article directly, it did mention a young reporter named MacNamara. MacNamara was apparently a friend of Gustave Whitehead, and at that time, the editor of the Bridgeport ‘Times’. This would seem to suggest him as another possible author of the Herald article.

In December 1936, in response to the Popular Aviation article, Harvard University economics professor John B. Crane issued his own article. Published in National Aeronautic Magazine, his article disputed the claims that Whitehead flew. However, a year later, after additional research, Crane had reversed his position. He now believed that there was something to Whitehead’s claims, telling reporters, “There are several people still living in Bridgeport who testified to me under oath, they had seen Whitehead make flights along the streets of Bridgeport in the early 1900s.” He suggested that the matter was worthy of a Congressional investigation.

In 1937, Randolph expanded the Popular Aviation article into a book, “Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead.” She had tracked down a variety of people who had known Whitehead and claimed to have seen his flights. She was able to gather 16 affidavits from 14 different people and included the text of those affidavits as part of the book. 4 of the 14 people providing affidavits said they did not see an actual flight, but swore to their belief that they happened. The remaining 10 all swore to seeing flights, ranging from forty or fifty feet to hundreds of feet and even more than a mile. Randolph also stated in the book that she now believed Richard Howell to be the author of the unsigned Herald article.

Here are some compelling excerpts from three of the affidavits, including Louis Davarich, Whitehead’s co-pilot from the 1899 flight:

Affidavit: Louis Davarich – 14 July 1934:

“In approximately April or May, 1899, I was present and flew with Mr. Whitehead on the occasion when he succeeded in flying his machine, propelled by steam motor, on a flight of approximately a half mile distance, at a height of about 20 to 25 feet from the ground. This flight occurred in Pittsburgh, and the type machine used by Mr. Whitehead was a monoplane. We were unable to rise high enough to avoid a three-story building in our path and when the machine fell I was scalded severely by the steam, for I had been firing the boiler. I was obliged to spend several weeks in the hospital, and I recall the incident of the flight very clearly. Mr. Whitehead was not injured, as he had been in the front part of the machine steering it.”

Affidavit: Michael Werer – 24 September 1934

“On about Sept or Oct 1901 I was present on the occasion when Mr. Whitehead succeeded in flying his machine, propelled by motor on a flight of about four hundred feet, at about six feet off the ground, for a length of time approximating half minute.

The type of machine used by Mr. Whitehead was a folding wing Monoplane. This flight took place on Tunxis Hill Road near Mountain Grove Cemetery, Bridgeport, Connecticut.”

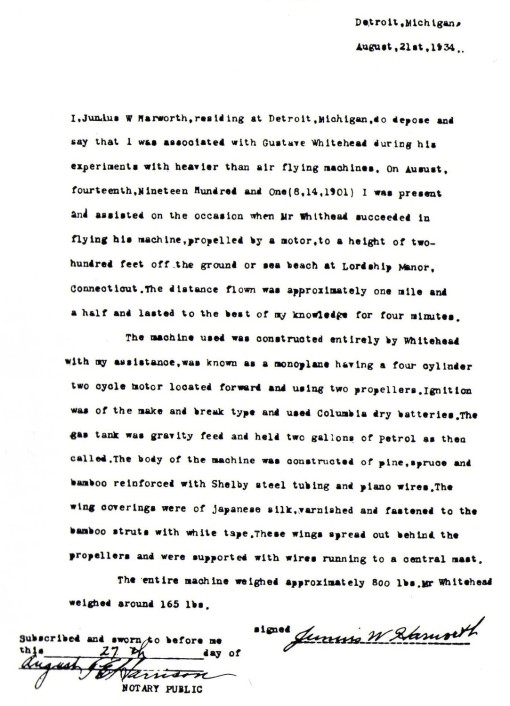

Affidavit by Junius Harworth – 21 August 1934:

“On August, fourteenth, Nineteen Hundred and One I was present and assisted on the occasion when Mr. Whitehead succeeded in flying his machine, propelled by a motor, to a height of two hundred feet off the ground or sea beach at Lordship Manor, Connecticut. The distance flown was approximately one mile and a half.”

In 1949, Crane published a second article, this time in Air Affairs magazine, and came out in support of the claims that Gustave Whitehead flew. Interestingly, this second article makes no mention of his first article, and makes to effort to refute any of the evidence he provided against Whitehead in his first article.

Things quieted down again for a while, until in 1963, when US Air Force Major William O’Dwyer made an accidental discovery. He found a photograph collection in the attic of a Connecticut residence that contained many images of a large ‘Albatross’ style Whitehead biplane. O’Dwyer and some members of his squadron were asked by the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association to look into Gustave Whitehead’s stories, and try to determine if he had actually been able to make powered flights or not.

O’Dwyer kept researching for years, becoming more and more convinced that Whitehead had achieved flight before the Wright Brothers. Stella Randolph, working on a second book about Whitehead, approached O’Dwyer about his research. O’Dwyer gave her several interviews from people claiming to have seen the flights, and she published this book ‘The Story of Gustave Whitehead, Before the Wrights Flew’ in 1966.

In 1968, also based off this new research, Connecticut chose to officially recognize Gustave Whitehead as the ‘Father of Connecticut Aviation.’ This didn’t sit well with North Carolina. Holding to the Klingon proverb ‘Revenge is a dish best served cold,’ North Carolina waited 17 years to strike. But strike they did, when in 1985 the North Carolina General Assembly passed a resolution repudiating the Connecticut claim:

“Whereas, North Carolina, is where aviation began. It is hallowed ground. The events and accomplishments that occurred have been recorded through eighty-three years of aviation history. It is where man’s first sustained, controlled, powered flight happened at 10:35 a.m. on December 17, 1903…

Whereas, the North Carolina General Assembly repudiates the contention of a group of Connecticut residents and that State’s Legislature, that Gustave Whitehead, a resident of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was the first man to achieve sustained, controlled flight in a heavier than air machine on August 14, 1901; and

Whereas, there is no historic fact, documentation, record or research to support the claim that Gustave Whitehead flew before the Wright Brothers. The Whitehead claim has been discounted by leading aviation historians and the world’s largest aviation museum – The Smithsonian Institute…”

In 1975, O’Dwyer made another discovery, regarding a contract between the Wright Brothers and the Smithsonian. In order to fully understand this contract, it’s necessary to backtrack a little to 1901. Smithsonian secretary Samuel Langley was working on building a full size version of his Aerodrome aircraft, when word of Gustave Whitehead’s flights reached their ears. Whitehead’s aircraft Number 21 was currently on display in Atlantic City, and Langley’s chief engineer, Charles H Manly, was interested in the particulars of the aircraft. He didn’t believe the claims of flight, so he dispatched FW Hodge, a staff clerk, to view Number 21. He requested Hodge report on the size and dimension of the tail, wings, propellers, and the construction of the propeller drive and the aircraft itself. Manly was also particularly interested in the aircraft’s acetylene engine. After his viewing, it was Hodge’s opinion that the Number 21 wasn’t airworthy.

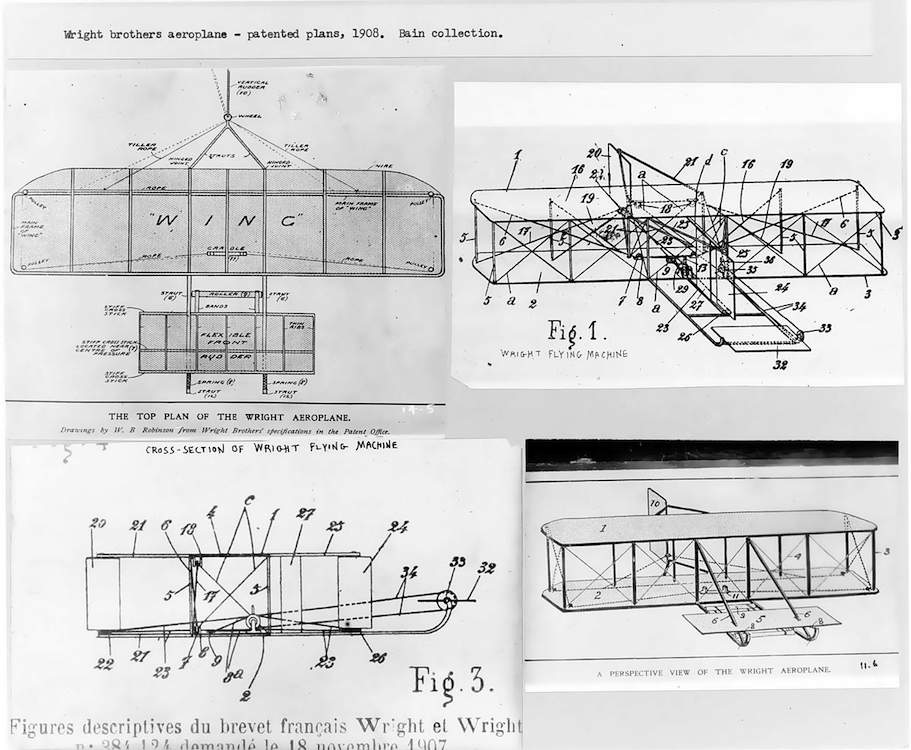

Jumping ahead 9 years, Langley had failed in both of his attempts to fly the Aerodrome, and the Wright Brothers were riding high. Orville offered the Smithsonian the restored Wright Flyer 1 for display, but they instead turned to Glenn Curtiss (currently engaged in a lawsuit with the Wright Brothers) to rebuild the Aerodrome to its original specifications. Unknown to the general public, the Smithsonian team and Curtiss made several major design improvements. In 1914, Curtiss and his team then made several brief, successful flights with the rebuilt Aerodrome. After this, the Smithsonian covertly restored the new craft to the original specifications, and then put it on display as the first heavier than air craft that was capable of powered, manned flight. Orville was extremely insulted and spent several years trying to get the Smithsonian to change this, before finally shipping the restored Wright Flyer 1 overseas for display in London.

Shortly after Orville’s death in 1948, the Wright Flyer 1 was returned to the states and found a home in the Smithsonian. However, there was a condition for being able to display the plane:

“Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities, administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.”

Further, if the Smithsonian ever failed to keep this condition, the Wright family was allowed to reclaim the Flyer. The Smithsonian agreed and signed the contract. Of course, this agreement was never made public.

OK. Now back to 1975. O’Dwyer hears about the contract from Harold S. Miller, who is serving as en executor to the estate of Orville Wright. O’Dwyer, with the help of Connecticut US Senator Lowell Weicker, and the Freedom of Information Act, was able to have the contract released to the public. This led to O’Dwyer and Stella Randolph co-authoring the book ‘History by Contract’ (published in 1978), which argued that the contract between the Smithsonian and the Wright’s estate unfairly suppressed any recognition of Gustave Whitehead’s achievements. The book also called for an immediate end to the contract3.

The Smithsonian claimed that the agreement was only put in place to end the feud between them and the Wrights over the false Aerodrome claims. In 2005, Peter Jakab, speaking for the Smithsonian, said:

“We would present as accurate a presentation of the history of the invention of the airplane as possible, regardless of the consequences this might incur involving the agreement. Having said that, however, at this time, as in 1948, there is no compelling evidence that Whitehead or anyone else flew before the Wright brothers.”

The agreement still remains in effect today.

Finally, just two years ago, ‘Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft’ (a popular annual aviation publication about the worldwide aviation industry) officially recognized Gustave Whitehead as the first person in history to carry out a sustained, powered, and controlled flight on 14 August 1901. This decision was based largely on research carried out by Australian aviator John Brown. Brown, becoming aware of Whitehead’s story and legacy in 2012, carried out his own extensive research on Whitehead. He poured through articles, letters, testimonies and photos, becoming more and more convinced Whitehead claims were true. And then he found what many consider to be the ‘Smoking Gun.’

In 1906, Whitehead, along with the Wright Brothers, Octave Chanute, and others, had been part of the first Aero Club of America exhibition in 1906. Included with his material were photographs. And though those photographs have not been found, there is an existing photograph of the exhibit hall. Brown, conducting what he described as forensic analysis on the exhibit hall photograph, claims that one of the photos in the Whitehead exhibit was indeed the ‘lost photo’ of Number 21 in flight, the photo that inspired the drawing accompanying the article.

Connecticut, once more spurred on by this interest in Whitehead, took the opportunity to again recognize his accomplishments. They enacted a law saying that ‘Powered Flight Day’ honor Gustave Whitehead rather than the Wright Brothers:

“This act requires (1) the governor to proclaim the following months and day of each year to honor Americans of different ancestry and (2) suitable exercises to be held in the State Capitol and elsewhere as the governor designates:

1. March as Irish-American Month,

2. October as Italian-American Month,

3. November as Native American Month, and

4. June 24 as French Canadian-American Day.

The act also establishes (1) the ballroom polka as the state polka and (2) Beautiful Connecticut Waltz, composed by Joseph Leggo, as the second state song. It specifies that Powered Flight Day is in honor of the first powered flight by Gustave Whitehead, rather than the Wright Brothers.”

Also, someone really wanted the ballroom polka to get its proper recognition as well. Though North Carolina hasn’t responded yet, expect something devious in about 10 – 12 years.

Gustave Whitehead’s Critics Respond

So, backed by respected figures like Randolph, O’Dwyer, Crane, Brown and others, and given a large amount of solid evidence, is there really a doubt Gustave Whitehead flew first? Well, yes. The Wright Brothers also have some impressive supporters. These include, among others, aviation historians Charles Gibbs-Smith and Caroll F Gray, and Thomas Crouch, senior curator in the Aeronautics Department at the National Air and Space Museum. And they have done a significant amount of work to cast doubt on the evidence for Gustave Whitehead, starting with the Bridgeport Herald article.

According to Gray, the Herald article was not an original piece, but an embellished reprint on a previously existing piece, and she makes a compelling argument for this being the case:

“The June 9, 1901, New York Sun page two article presents a serious problem for those who have promoted and defended the anonymous page five Sunday Herald report of August 18, 1901 – the Sun story appeared ten weeks earlier than the Sunday Herald’s article.

In short, it means that the Bridgeport Sunday Herald article was simply a broad re-write of the earlier New York Sun article about tests made on May 3, 1901, which was then grafted onto a number of previously printed articles, and combined with the unsubstantiated ‘news’ about Texan William D. Custead and Gustave Whitehead forming a partnership to build airships and airship powerplants.”

One of the two eyewitnesses the article cites, James Dickey, also later denied being there. In a 1937 affidavit obtained by Stella Randolph, Dickie says he wasn’t present at the flight, didn’t know who Andrew Cellie (the other eyewitness) was, and that as far as he knew, none of Whitehead’s aircraft ever flew. O’Dwyer, who was in contact with Dickey during his research in the 60s, claims that Dickey’s affidavit was compromised by a grudge against Whitehead:

“… his mood changed to anger when I asked him about Gustave Whitehead. He flatly refused to talk about Whitehead, and when I asked him why, he said: ‘That SOB never paid me what he owed me. My father had a hauling business and I often hitched up the horses and helped Whitehead take his airplane to where he wanted to go. I will never give Whitehead credit for anything. I did a lot of work for him and he never paid me a dime.’”

Randolph was unable to find Andrew Cellie4 for comment.

In 1945, Gustave Whitehead’s son Charles gave an interview on a national radio program, and was called the son of the first man to fly. This claim was further spotlighted by a Reader’s Digest article shortly after. This article stirred none other than Orville Wright into action, who wrote a scathing rebuttal that appeared in the August 1945 issue of US Air Services. He based much of his response on the testimonies of three people: James Dickie, Stanley Beach and John Dvorak. Dvorak, a physics professor, had hired Gustave Whitehead to build an engine from Dvorak’s plans5:

“I personally do not believe that Whitehead ever succeeded in making any airplane flights. Here are my reasons: 1. Whitehead did not possess sufficient mechanical skill and equipment to build a successful motor. 2. Whitehead was given to gross exaggeration. He was eccentric – a visionary and a dreamer to such an extent that he actually believed what he merely imagined. He had delusions.”

As previously noted, Dickie appears to have had a grudge against Whitehead, and it appears Beach (the editor of Scientific American) may have held a grudge as well, which we’ll get into shortly. Orville, and many critics since, have used this statement from Beach against Whitehead:

“I do not believe that any of his machines ever left the ground under their own power in spite of the assertions of many persons who think they saw him fly.”

Interestingly, Beach did concede some credit, adding that Gustave Whitehead:

“…deserves a place in early aviation, due to his having gone ahead and built extremely light engines and aeroplanes. The five-cylinder kerosene one, with which he claims to have flown over Long Island Sound on 17 January 1902 was, I believe, the first aviation Diesel.”

In the late 50’s, London-based aviation researcher Charles Gibbs-Smith stepped in the arena. After pouring through all the available material, he found in favor of the Wright Brothers, saying that reports that Gustave Whitehead achieved successful flight before the Wrights were fabrications.

“Unfortunately, some of those who advanced [Whitehead’s] claims were more intent on discrediting the Wright brothers than on establishing facts.”

He also said that no reputable historian believed Whitehead’s claims and that if Gustave Whitehead had experienced true success, he would have had widespread recognition.

Nick Engler, who runs an educational website on the Wright Brothers, had this to say:

“While Whitehead believers insist that he was first to fly, no one claims that his work had any effect on early aviation or the development of aeronautic science. Even if someone someday produces a photo of No. 21 in flight on August 14, 1901, it will be nothing more than a footnote, a curious anomaly in the history of aviation.”

Speaking of photos, Gray again came out swinging when John Brown released his analysis of the 1906 exhibit hall photo. She released her own analysis, concluding that the photo in question was of a different aircraft altogether, John J. Montgomery’s glider The California.

“This identification of the Blurry Image as Montgomery glider The California on May 21st of 1905 at Agricultural Park ought to cause Mr. Brown to retract both his “forensic” examination and his conclusion as to what the Blurry Image shows. The Blurry Image does not show Gustave Whitehead in flight in 1901. Somehow, it seems doubtful Mr. Brown will be willing to admit his mistake, as he has so much invested in his “forensic” examination of the Blurry Image.”

Also in response to Brown’s research and Jane’s proclamation of Gustave Whitehead as the aviator to achieve first flight, Tom Crouch fired off an article of his own, reaching this conclusion:

“My conclusion–either Whitehead had somehow forgotten the secrets of flight, or he had never flown a powered machine at all.

In its issue of December 26, 1903, just three months after Scientific American had reported Whitehead’s experiments with an obsolete hang glider, the journal noted that the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright had made some “successful experiments” with a powered flying machine operating under the complete control of a pilot. Unlike Whitehead, who had kept virtually no record his experiments, the Wrights had documented their work in detailed, notebooks, letters, and photographs, including what is arguably the most famous photograph ever taken.

I rest my case.”

Can Someone Both Support and Work Against Gustave Whitehead?

Which brings us back to Stanley Beach. Beach, in the early days, was a friend of Gustave Whitehead. Several articles published in Scientific American talk of Whitehead and his aircraft. The first, in June of 1901, makes mention of Whitehead’s tests. And though it doesn’t mention flight, multiple articles in 1903, 1906 and 1908 state that Whitehead had achieved ‘short flights’ and flown ‘short distances’ in 1901. At least some of these articles, though published without an author credit, were later claimed by Beach.

However, in 1905, Beach and Whitehead submitted a patent for a monoplane glider. This patent was granted in 1908, and Whitehead built the glider, which was unable to fly because it was underpowered and too heavy. When Whitehead told Beach that he felt the design was faulty and couldn’t be made to work, Beach had men take the aircraft from Whitehead’s workshop. After this, their relationship became rocky, and Beach started associating with the Wright Brothers. Many of Beach’s later critical statements about Gustave Whitehead contradict what he said earlier, and what was written in the articles.

OK, OK, but what about Karl Jatho and Richard Pearse?

Who, you may ask? Well, Jatho and Pearse are two other contemporaries of Gustave Whitehead and the Wright Brothers who may have achieved flight around the same time. I know, I know, it’s not like the question of first flight wasn’t already tangled enough. Karl Jatho was a German inventor and aviation pioneer. In 1903, from August through November, Jatho made a series of progressively longer flights at Vahrenwalder Heide, near Hanover. He started flying a ‘pusher’ style Triplane, and then moved to a biplane.

His first flight was uncontrolled, and only about 60 feet (18 m) at an altitude of 3 feet (1 m). By November (1 month earlier than the Wright Brothers), he could fly about 195 feet (60 m) at an altitude of roughly 10 feet (3 m). Eventually, discouraged by his results, Jatho gave up, noting:

“In spite of many efforts, (I) cannot make longer or higher flights. Motor weak.”

After discontinuing his flight experiments, Jatho founded both a flying school and an aircraft factory. However, he did not enjoy success with either of these ventures.

So that leaves Richard Pearse. An inventor and aviator in New Zealand, Pearse began attempting flights in 1901, but his engines lacked the power to lift his craft for more than brief ‘hops’. Pearse then designed and built a new engine, this one a two cylinder ‘oil engine’. This was mounted on a tricycle undercarriage, which had a bamboo wing structure and air frame covered in linen. This design, interestingly, resembled modern aircraft more than the Wright Brother’s design. It was a monoplane rather than biplane, used a tractor propeller rather than a pusher propeller, had the stabilizers and elevators located at the rear of the aircraft rather than the front, and used ailerons for controlling banking rather than wing warping.

Replicas of Pearse’s engine suggest that it was capable of producing about 15 hp. Using this new craft, witnesses claim Pearse was able to make at least four flights:

Flight 1 – 31 March 1903. Pearse covered an estimated distance of 1,050 feet (320 m) in a straight line, with poor control, before landing.

Flight 2 – Sometime after the first flight, before May 1903. Pearse made another successful flight, of about 450 feet (137 m).

Flight 3 – 2 May 1903. Pearse took off, traveled a short, but unknown distance, and crashed into a gorse hedge (a thick hedge with nasty spines).

Flight 4 – 11 May 1903. Pearse took off from a sight alongside the Opihi River, about 4.3 m (7 km) outside the town of Temuka. He was able to gain enough altitude to turn left and clear the 30 foot (9 m) river bank, then turn right, and fly parallel to the bank over the middle of the river. After Pearse flew for nearly 3,000 feet (914 m), the engine on his aircraft began to overheat, and he was forced to land in the mostly dry riverbed.

So why is so little known about Pearse? In addition to working in the relatively small and remote New Zealand aviation industry, Pearse’s work was poorly documented. There were no contemporary newspaper articles or coverage of his flights, few photographs survived, and the ones that did are undated and often blurry or otherwise difficult to tell exactly what is going on. Pearse was also somewhat eccentric and made conflicting statements about his flights, often confusing historians and making dates hard to pin down. And though he had many modern notions of aircraft design, such as ailerons, and lightweight air-cooled engines, his impact on the field of aviation was small, due to his remote location and lack of records.

Though he continued experimenting, inventing, and building well into the 1940s, Pearse eventually became more and more erratic, believing that foreign spies were after his research. He was eventually committed to a mental hospital in 1951, where he died two years later. It is believed that much of his research was destroyed around this time.

And so? The Upshot of All This First Flight Controversy?

It seems fairly certain that the Wright Brothers were not the first to achieve powered, manned flight. Even on Nick Engler’s website devoted to the Wright Brothers, you can find this:

“While the Wright brothers may have been the first to make a sustained, controlled flight, they were just two among hundreds of brave men and women who helped to give the world its wings during the earliest days of aviation.”

As the quote suggests, however, they may have been the first to achieve sustainable, repeatable, and controllable powered flight. Which, according to many historians, is what actually matters. And it’s hard to discount the momentous achievement of their flights, and their impact on aviation, even in the face of their extremely litigious nature and occasionally, well, jerkish behavior.

Gustave Whitehead and others, however, also have fascinating stories, and strong claim to some of the fame and fortune the Wright Brothers enjoyed. There exist a vast collection of additional pieces of evidence and other claims from both sides, including a rumored meeting between Gustave Whitehead and the Wright Brothers in 1901 or 026. One could spend months reading, researching, and gathering opinions and evidence from both sides, and still not reach the bottom.

So who did achieve the first manned, powered flight in a heavier than air aircraft? We may never know for sure. But one thing that is certain is that these early aviators poured themselves, their energy, and their passion into the field of aviation, and achieved incredible, monumental feats, worthy of our respect and admiration.

Footnotes:

1 – During 1901, Gustave Whitehead built 56 aircraft. He was not in the habit of naming them, so they were simply known by their number.

2 – In the first letter Gustave Whitehead sent American Inventor magazine later that year, he indicated this was only one of four successful test flights that day, the longest being an estimated 1.5 miles (2.4 km).

3 – George Gunther, a Connecticut state senator from 1966-2006, says that History by Contract was far too heavy handed. He claims to have been having encouraging conversations with the Smithsonian regarding Gustave Whitehead, and possibly restoring some credit to him. However, after they were blasted by O’Dwyer and Randolph in the book, the Smithsonian decided they were no longer interested in giving Whitehead any credit.

4 – O’Dwyer, during his research, came to the conclusion that Andrew Cellie was never found due to the newspaper misspelling his name. He believes it was actually Andrew Suelli, an immigrant and Gustave Whitehead’s neighbor in Pittsburgh. Though he had long since died, O’Dwyer was able to find neighbors of Suelli who said that he always claimed he was present during Whitehead’s 1901 flight.

5 – Junius Harworth, Gustave Whitehead’s assistant at the time, claimed in an affidavit that the engine failed because Dvorak insisted on using his own design. According to Harworth, Dvorak lacked the mechanical skill to make a good engine.

6 – Gustave Whitehead’s supporters claim the Wrights, who viewed Whitehead’s aircraft, stole many of their ideas for the Wright Flyer from this meeting. The Wright’s supporters say the meeting never took place, and the Wright’s themselves say that the first time they came through Bridgeport was in 1909.

Sources:

In addition to the links scattered throughout the articles, here are some other links I found fascinating and useful in my research of this story:

– This link from historian Nick Engler’s site provides you with the text for four important articles in the Gustave Whitehead v. Wright Brothers debate: The Stella Randolph / Harvey Phillips Popular Aviation article; the original Bridgeport Herald article, with accompanying pictures; Gustave Whitehead’s letters to the American Inventor magazine; and John Crane’s original 1936 article against Gustave Whitehead:

Engler, Nick. “Whitead Articles” Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company. n.d. Bookworks, Inc. Web. 30 January 2015.

And from the same site is a Wright leaning view of Gustave Whitehead:

Engler, Nick. “Gustav Whitehead” Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company. n.d. Bookworks, Inc. Web. 1 February 2015.

– And here you can find a site with material squarely in Gustave Whitehead’s corner:

Also, another great resource on this site is their collection of affidavits supporting Gustave Whitehead and his claims of first flight:

//www.gustave-whitehead.com/history/witness-statements/

– Wikipedia has very helpful pages for both Gustave Whitehead (//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Whitehead) and the Wright Brothers (//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wright_brothers) though some people have claimed the Gustave Whitehead wiki is edited with a Wright slant.

I am the daughter of Maj. William J. O’Dwyer, Whitehead researcher, and have been associated with the Whitehead research since 1963. I am the author of the new, definitive works, “Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight” (Brinchman, 2015), addressing many of the issues brought forth in this article. For instance, during the course of the research for my book, I located primary source information proving the Smithsonian-Wright Agreement of 1948 was contrived by Orville Wright’s close associates, who’d been vigorously helping him fight the Whitehead claim for the past decade. Also, I identified 11 local news articles that credited Whitehead for his early flights in 1901. Much of the information used to fight the Whitehead claim then and now is inaccurate. Read “Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight”, fully documented, to make your decision! It’s available on Amazon.

PS There are a number of mistakes in the article above, including that in 1913 “the courts found against Whitehead.” There is no evidence of this in the historical record. During the Wright-Curtiss patent wars, Whitehead was briefly considered to provide testimony but the judge ruled this irrelevant to the matter at hand, and thus, Whitehead never became involved, according to my understanding.