Or, how the Government nearly got rid of home-built aircraft.

The current FAA regulations for experimental amateur-built (or homebuilt) and kit-built aircraft state:

‘Special airworthiness certificates may be issued in the experimental category for:

- Operating amateur-built aircraft: to operate an amateur-built aircraft in which the major portion has been fabricated and assembled by persons for their own recreation or education.

- Operating kit-built aircraft: to operate a primary category aircraft that was assembled by a person from a kit manufactured by the holder of a production certificate for that kit, without the supervision and quality control of the production certificate holder.‘

This ability to certify and fly homebuilt and kit-built aircraft allows a great deal of satisfaction for a large number of aviation enthusiasts. But it wasn’t always this way, and after an initial burst of amateur building in the pioneering days of aviation, the homebuilt aircraft was almost regulated out of existence, before being revitalized in the 1950s. As it turns out, the history of the experimental certificate is a long and winding road. So, how did it all happen?

The Dawn of Homebuilt Aircraft

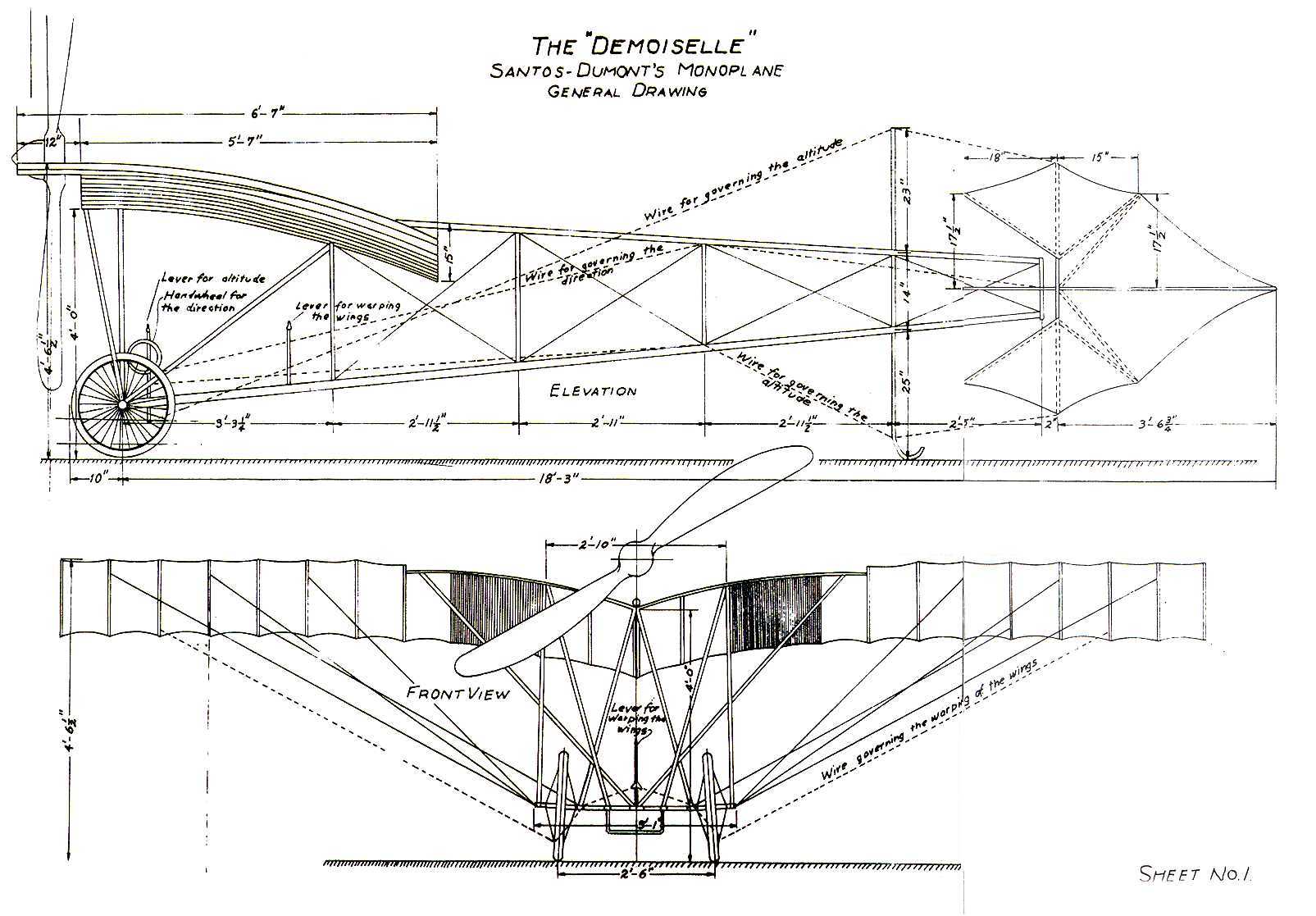

Well, after the Wright Brothers’ first successful powered flight on December 17th, 1903, the doors to the world of aviation were thrown wide open, and inventors, enthusiasts, entrepreneurs, and dreamers poured through those doors into this exciting new world. By 1908, Short Brothers plc was founded in London, becoming the first company in the world to make production aircraft. At the same time, Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont, the son of Brazilian ‘Coffee King’ Henrique Dumont, started working with Adolphe Clement, and the Clement-Banyard company, to mass-produce Santos-Dumont’s own ‘Demoiselle‘ airplane design[1], a personal use monoplane which became the world’s first series production aircraft.

In June of 1910, Santos-Dumont allowed Popular Mechanics magazine to publish the plans for the ‘Demoiselle‘, making it the first free and publicly available aircraft design.

And with this ringing endorsement from the magazine:

“This machine is better than any other which has ever been built, for those who wish to reach results with the least possible expense and with a minimum of experimenting.“

Alberto Santos-Dumont became a defining figure in the field of homebuilt aircraft. In the years that followed, many designs were tried, shared, modified, and experimented with as the homebuilt market took off (pun fully, completely, totally intended). In 1924, with the start of the National Air Races held in Dayton, Ohio, the homebuilt market exploded, in part because of the races requiring aircraft with useful loads of 150 pounds, and engines of 80 cubic inches or less. Coupled with amazing aviation feats such as Charles Lindbergh’s astounding 1927 trans-Atlantic flight, the period of time from the early 1920s to the early 1930s gave rise to a vast number of homebuilt aircraft[2], as can be seen in this period video showing off some of the crazy designs, successes and failures from the era:

The History of the Experimental Certificate

However, as many of the aircraft designers, builders, and pilots from this period were self taught, the accident rate rose dramatically. This brought heavy criticism and condemnation from the public and the growing aviation industry, and in response to the question of ‘Should pilots build aircraft?’ the Government passed ‘The Air Commerce Act’ of May 20, 1926, much of which continues to serve as the cornerstone of governmental regulation of aviation. This act put the Secretary of Commerce in charge of encouraging aviation related commerce, setting and enforcing air traffic rules, licensing pilots, properly certifying aircraft, creating and maintaining airways, and developing, deploying and maintaining a variety of aids to air navigation[3]. To handle the tasks related to aviation oversight, the Aeronautics Branch was created, operating under the direction of the Department of Commerce. By the early 1930s, the federal standards on design, engineering, stress analysis, construction material, and aircraft testing effectively ended amateur home building, except in a few very small, specialized pockets of aviation.

In 1934, the Aeronautics Branch was renamed the Bureau of Air Commerce, and they began working with groups of airlines to create the first three centers for providing air traffic control (ATC) services along established airways. Then, in 1936, the Bureau of Air Commerce took direct control of the centers, and started expanding the ATC system. These original air traffic controllers used maps, blackboards, and (hopefully) sound mental calculating to ensure the safe separation of the many aircraft now flying along the established airways between cities. Then, in 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Act relieved the Department of Commerce of their federal civil aviation responsibilities and transferred those to a newly formed independent agency called the Civil Aeronautics Authority. This act also gave the newly formed CAA the authority to regulate airline fares and decide which routes the various airlines could serve.

A scant two years later, in 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a new agency, the Civil Aeronautics Board, and gave them a portion of the CAA’s responsibilities. While the CAA still oversaw the ATC operations, airman and aircraft certification, enforcement of safety regulations and development of airways, the CAB was now responsible for creating safety regulations, investigating accidents, and economically regulating the airlines. This system stayed in place until 1958, until the dawn of jet travel and a series of devastating mid air collisions brought about the need for change. The most notable of these accidents was the 1956 Grand Canyon mid air collision that claimed 128 lives. This was the first aviation accident to claim over 100 lives. Spurred to action by these tragedies, the Government passed the Federal Aviation Act of 1958, establishing a new independent group, the Federal Aviation Agency, or FAA. The FAA took over all duties of the CAA, took back safety regulation related duties from the CAB[4], and was tasked with creating a common air traffic control and air navigation system between the civil and military sectors.

Homebuilding Makes a Comeback

Now, while all this Governmental back and forth was going on, leading to the eventual creation of the FAA, Goodyear quietly restarted the National Air Races in 1946, and included a racing class for aircraft powered by engines 200 cubic inches and smaller. This ‘Midget’ racing class became incredibly popular, and led to a call for the Government to issue acceptable standards that would again allow for the building and recreational use of amateur, homebuilt aircraft. And in October of 1952, the Government did just that, including an experimental amateur built category in the Civil Aeronautics Manual for the first time, effectively re-opening the doors for the homebuilt aircraft. Perhaps not so coincidentally, it was around this same time, in January of 1953, that the Experimental Aircraft Association was founded in Wisconsin. Since then, the EAA has become the premiere homebuilt aircraft association, with a strong national presence, and a yearly gathering in Osh Kosh that draws worldwide attendance.

With the CAA (soon to be FAA) once again allowing amateur homebuilt aircraft, the homebuilt aviation enthusiasts once again went to work. And in the nearly 60 years since this period, there have been many interesting changes, and interesting pieces of information that we’ve learned along the way, a few of which I’d like to talk about here.

First, though many people think of airplane kits being available and kit building starting at roughly the same time as homebuilding, this isn’t entirely accurate. Most of the early homebuilt planes were built more or less from scratch, on occasion aided by plans. Ed Heath is generally credited with offering the first ‘kit-plane’ in the 1920s, the ‘Heath Parasol‘:

and though there were others along the way, kit-building didn’t really take off until Frank Christensen achieved a breakthrough in 1977 with the Christensen Eagle II (later known as the Aviat Eagle II) biplane kit. This biplane kit, a two seat aerobatic model, came with a new engine, a stack of manuals estimated by some to be 8 feet high, and a large number of finished parts. Too many finished parts, it turned out, as the FAA actually made Christensen stop supplying buyers with a full set of finished wing ribs, so that the builders had to do more of the work for themselves. An incredibly popular and widely sold kit, as of 2011, there are still 350 operating Christensen Eagle 2 kit planes.

Second, there is a higher accident rate with homebuilt and kit-built aircraft versus certified general aviation aircraft. In a 2012 study released by the NSTB entitled ‘The Safety of Experimental Amateur Built Aircraft’, it was found that while the nearly 33,000 homebuilt planes accounted for almost 10 percent of the general aviation fleet, they accounted for 15 percent of the total, and 21 percent of the fatal, US General Aviation accidents in 2011. Former FAA Administrator Randy Babbit believes one of the problem areas is the first 20-40 flight hours after transfer of ownership:

‘It’s not the builders [getting into accidents], but the second owners. We need better transition training.‘

Interestingly, the NTSB study also revealed that though there has been a decline in overall general aviation flight activity during the last 10 years, the experimental, amateur-built segments have grown, both in number of aircraft, and flight activity.

And finally, with home and kit-builders having access to a wide array of building materials, a lot of different plans, and an occasionally questionable sense of style, there have been some wild, crazy and unique homebuilt experimental aircraft. Here, for your consideration, are my three favorite:

1 – The Bumblebee 2 designed and built by Robert Starr

2 – The Rutan Boomerang designed and built by Burt Rutan

3 – The Junqua Ibis designed and built by Roger Junqua

There’s a wide world out there, and aviation has been a key in drawing us all a little closer together. And though there are definitely safety concerns to be aware of, with care, patience and adherence to the guidelines, a homebuilt aircraft can be a wonderful, and unique expression of your passion for aviation.

——————————————-

[1] – The ‘Demoiselle‘ was planned to have a production run of 100 units, but only 50 were built, and only 15 were sold, at a cost of 7,500 francs for each airframe. By 1909, the ‘Demoiselle‘ was offered with a choice of three engines: the Clement 20 hp; the Wright 4-cylinder 30 hp (which Clement-Bayard had licensed the right to manufacture from Wright engines) and the Clement-Bayard 40 hp, designed by Pierre Clerget. The ‘Demoiselle‘ was capable of achieveing speeds of close to 75 miles per hour.

[2] – In 1929, the ‘Ace Baby Ace’ became the world’s first marketed homebuilt aircraft when its plans were offered for sale. And with plans still available, the Ace Baby Ace and other variants are being built, even today.

[3] – This included taking over the creation of the first transcontinental air route from the Post Office, part of which was creating those giant arrows and light beacons, and working to improve aerial radio communication, including introducing radio beacons as an effective navigation aid.

[4] – The CAB continued on until it was closed in 1985. Along the way, the NTSB was formed in 1967 and took over the CAB’s accident investigating responsibilities, with the US Department of Transportation eventually taking over the rest.

Sources: FAA, NTSB, EAA, Wikipedia

3 Comments