A truly gifted engineer, Hugo Junkers work in aviation truly began at the age of nearly 50.

Hugo Junkers was born on February 3, 1859, Rheydt, in Rhine Province of Prussia to successful German industrialist, Johann Heinrich Junkers and his wife, Luise Junkers. Naturally gifted with mechanics and engineering as his father was, Hugo Junkers passed his Abitur (a German university-preparatory school exam) and left to attend the Royal Polytechnic University in Charlottenburg, Germany and the Royal Technical University in Aachen, Northern Rhine Province, where he completed his engineering studies in 1883.

After receiving his degrees, Junkers returned home to work at his father’s factory but was enamored by a series of lectures on electromagnetism and thermodynamics by German electronics pioneer Adolf Slaby. Slaby recognized his preternatural talent for engineering and moved Junkers to Dessau to work for the Continental-Gasgesellschaft company, where he worked on the world’s first opposed-piston engine.

Boilers, Radiators, and Metallurgical Patents

Despite his lasting legacy within the world of aviation, Junkers’ many non-aviation related inventions (including the calorimeter, the gas-fired bath broiler, gas stoves, pressure regulators, gas-oil engines, fan heaters, and more) earned him fame and recognition in his field, and a lecturing position on mechanical engineering at one of his prestigious alma maters, The Royal Technical University, where he taught until 1912. Junkers had founded the company Junkers & Co. in 1895 to better utilize his inventions and would gain substantial profits during this time to allow him to finally, at nearly 50 years old, pursue his secret interest in aviation.

Hugo Junkers and the Flying Wing

In 1908, Hugo Junkers was invited by his colleague Jacob Johannes “Hans” Reissner to assist him in the design of an all-metal aircraft. Reissner, a German engineer and future Iron Cross recipient, brought Junkers and his corrugated iron wings (built in the Dessau Junkers & Co. factory) to Aachen. Unfortunately, their work came to a grinding halt when the German government required them to focus only on producing aircraft for the war effort at the outset of WWI.

During this time, Junkers patented iron wings, invented hydraulic brakes, and created (and patented) the concept of a Nurflügel, or a Flying Wing.

Building an All-Metal Aircraft Against the Odds

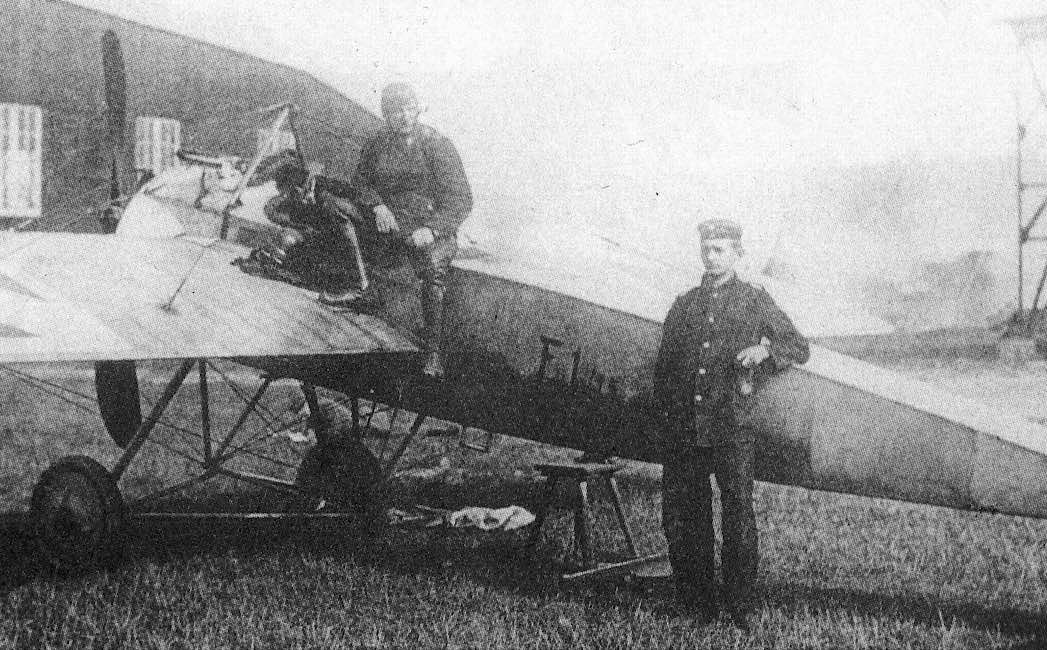

In 1915, Junkers and Reissner had managed to complete the first practical all-metal aircraft design, the Junkers J.1. The most desirable light-weight metal for aviation engineers was the newly created alloy (developed in 1909 by metallurgist Alfred Wilm), duralumin. The alloy, composed of primarily aluminum (which was still very expensive) with added copper, magnesium, and manganese was incapable of being used in sheet metal form due to flaking, leaving Reissner and Junkers with the unattractive alternative of a creating a heavy steel skin. This minor setback meant nothing to Junkers, whose factory workers in Dessau were capable of processing extremely thin sheets of metal, around just 0.1 to 0.2 millimeters thick.

Nicknamed the Blechesel or “Sheet Metal Donkey,” the hefty metal J.1 was utterly different than any other aircraft that existed at the time. Instead of wooden frames reinforced with wires and covered with stretched fabric, the J.1 utilized an all-metal load-bearing shell, referred to as a semi-monocoque design. (The J.1 was considered to be semi-monocoque because of its reliance on additional fuselage reinforcement through longitudinal steel stringers. A true monocoque design has no other additional reinforcement other than the tensile and compressive forces within the skin.)

Under the Cowl

The J.1 was remarkably heavy for an aircraft at the time, which Junkers knew would be detrimental to its maneuverability and climb capabilities. The J.1, in an attempt to recover those lost capabilities, was then fitted with a belly radiator for its 120 horsepower Mercedes D.II inline-six cylinder engine. The low drag from the sleek metal skin and belly radiator helped the J.1 become one of the fastest airplanes in the world at the time, with top speeds of 170 km/h (105 mph).

Belly radiator and all-metal semi-monocoque design aside, perhaps one of the most innovative designs of the J.1 were the thick cantilever wings. The massive wings, covered with sheet metal for added strength, had a wing root about 75% the height of the fuselage and featured three airfoil changes and tapered leading and trailing edges, a unique practical and aesthetic design that made the Junkers aircraft easily identifiable. Cantilever wings (wings that aren’t supported by wires or struts) had never been successfully used before, making them yet another aviation innovation attributed to Junkers.

The Junkers J.2: The First All-Metal Fighter Craft

Following the success of the J.1, which wasn’t intended for mass production, but to demonstrate the state-of-the-art technologies it utilized, Hauptmann Felix Wagenführ, head of Idflieg Prüfanstalt und Werft der Fliegertruppe (“Test Establishment and Workshop of the Aviation Troops” for the German Empires air force, the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte) requested Hugo Junkers build six all-metal fighter prototypes. The specifications required of the fighter prototypes included a top speed of 145 km/h (90mph), a flight endurance minimum of 90 minutes, and the ability to climb 3,000m (9,800ft) within 20 minutes.

The Junkers J.2, fitted with a 7.92 mm IMG 08 Spandau synchronized machine gun, made its first flight in July of 1916, less than a year later, making it the first all-metal aircraft intended as a dedicated military aircraft, as well as the first all-metal fighter aircraft. Due to the Luftstreitkräfte’s request for improved “nimbleness in the air,” the J.2 featured some aerodynamic improvements, including a rounded upper and lower fuselage section. The J.2 featured more than one design change new to the world of aviation, including the open cockpit roll bar, electrically roll-welded wings for added strength, and the “unitized” forward fuselage design, which combined steel framing around the engine mount, wing roots, and cockpit into one solid structure. When completed, the J.2, though smaller, weighed only slightly less than the J.1, which greatly hindered its climb rate.

The J.2 had a top speed of over 180 km/h (110mph), which made it the fastest plane of its kind by an impressive 16km/h (9.9mph). Idflieg test pilots reported excellent turning capabilities and aerodynamic behavior, but its slow climb rate led the Luftstreitkräfte to choose aircraft such as the Albatros D.I over the J.2 for combat on the front line.

The Spin I Spin II and Spin III: Anthony Fokker

Born on the island of Java, Anthony Fokker moved with his family to the Netherlands at age four and enjoyed a Dutch upbringing. Traditional school settings were not where Anthony thrived. In fact, he did not even complete his high school education. Anthony exhibited exceptional mechanical abilities from a young age and preferred working with model trains, steam engines, and model airplanes.

Seeking to build on this [Click here to read more…]

A Series of Never-Completed Prototypes and Pipe Dreams

The following engineering endeavor, the J.3, never made it out of the hangar, as the Idflieg officials began to doubt any further improvement on the monoplane design, instead requesting a sesquiplane to serve as J.4. Sesquiplane’s (from the Latin sesqui– meaning, “one and one-half”) are biplanes with one long wing and one short wing, which was usually on the bottom, and were possibly preferred over the traditional style biplane for their greater range of vision below the aircraft in aerial combat.

The History-Making J.I

Making history yet again, the J.4 became the first all-metal aircraft to enter mass production. Adopted by the Luftstreitkräfte as a member of their “J-class,” the J.4 was re-christened as the J.I. The J.I was developed specifically for low-level ground attacks and observation, instead of dogfighting like the J.2. It’s heavily shielded body was comprised of a steel “bathtub” shape that made up the main fuselage structure and engine mount, as well as added armor for the rear crew. The completely enclosed cowl could be opened on either side by vertically hinged three-part armored panels, roughly 5mm (0.20in) thick. The total armor added 470kg (1,036lbs) of weight to the already heavy plane, but it successfully protected the crew, engine, and fuel tanks from enemy fire, earning the love of its flight crew.

In another effort to protect the plane and crew, the traditional steel cable control surface connections were replaced by less convenient pushrods and bell cranks that were much less likely to be destroyed or severed by bullets. Additionally, in one of the first recorded instances of safety through redundancy in aviation, the main fuel tank (capable of holding around 120L/32gal) was divided into two parts, and was supplemented by a much smaller gravity-fed tank, which would provide 30 minutes of power in the event of a fuel pump failure. Another innovative military aircraft design was the J.I’s ability to be completely disassembled for ease of transport via truck or train, though it required four to six hours to be reassembled.

Powered by the 200 HP Benz Bz.IV six-cylinder, water-cooled engine, the J.I was still only capable of speeds up to 155 km/h (97mph) due to its weight. The J.I’s were used on the Western Front during the German Spring Offensive of 1918, and reportedly only one was ever shot down, but there are no sources to prove or dismiss that claim. Only one of the 227 J.I’s manufactured survives today, locked up as a war trophy in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

German Empire: Bringing Aviation Pioneers Together (Through Force)

After the production of the J.I, the German government forced Junkers to merge his company with Anton Herman Gerard Fokker, a Dutch aviation pioneer, and manufacturer, to form the Junkers-Fokker Aktiengesellschaft. The two men would go on to design and produce the world’s first low-winged, single-seat fighter aircraft, the Junkers D.I, which was the first instance of a completely duralumin airframe, as well as the Junkers CL.I and the CLS.I. The CL.I was Junker’s passive-aggressive defense of the monoplane, which he had been previously instructed to stop building, and experienced a very short production run in which only 51 were completed before the Armistice forbade Germany from building any more military aircraft. Three of the 51 planes were adapted into floatplanes, earning them the designation CLS.I.

Junkers Aircraft Works and the F.13

Once the war ended, Junkers, a pacifist, entered the civilian aviation market. By 1919, Junkers and Fokker, no longer bound together by the German Empire, had gone separate ways, leading to the creation of Junkers new company, Junkers Flugzeugwerke (“Aircraft Works”). Fokker reopened shop in the Netherlands, where he continued to produce excellent aircraft, such as the Fokker Trimotor.

Shortly thereafter, Junkers had built arguably the most modern looking aircraft in existence at the time, the F.13. The F.13 (the F stood for Flugzeug: “Air Craft”) was a single-engine, all-metal duralumin low-wing cantilever monoplane with all horn-balanced control surfaces, which would remain in production from 1919-1930, well past Junker’s previous record of a 2-year production run!

The F.13 made its first flight in June 1919, powered by a 170 HP Mercedes D.IIIa upright water-cooled engine, and featured a semi-enclosed cockpit for the crew, and an enclosed and heated cabin that could comfortably seat four passengers. In addition to cabin heating, which is remarkable for the time, the cabin had its own doors and windows, as well as seat belts!

The Short Life of the JG1 and Entering the Airline Market

After the success of the F.13, Hugo Junkers was determined to see his dream of a Nurflügel, or Flying Wing, become reality. His first order of business was to somehow create a giant aircraft capable of housing passengers inside the wings. Junker’s dream was beginning to take shape in the form of the JG1, but it was dismantled by the Allied Aeronautical Commission of Control due to its enormous size in 1921.

In 1927, Junkers won the Wilhelm Exner Medal for his advances in science that had a direct positive influence on the national industry. In 1930, Junkers was again recognized for his contributions to science with the highly prestigious Siemens-Ring from the Werner von Siemens Ring Foundation.

Over the next few years, Junkers stepped away from aircraft design and manufacture and began founding and developing airlines, such as Deutsche Luft Hansa (predecessor to Lufthansa) and Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano. The profits, however, weren’t rolling in fast enough, and after a failed venture to build planes for the USSR, Junkers lost control of most of his businesses, in lieu of loan repayments. In 1931, Junkers gave control of his businesses to communist activist Adolf Dethmann.

Machtergreifung, or the Rise of the Nazis…

After the 1933 Machtergreifung, the Nazi seizure of power, Hermann Göring (Goering), the new Reichskommissar of Aviation, requested Junkers and his businesses aid in the German re-armament. Junkers declined, to which the Nazi’s responded to by demanding ownership of all patents and market shares from his remaining companies under threat of imprisonment on the grounds of High Treason. Eventually, to ensure the safety of his wife, Therese, and their many children, Junkers agreed. By that point, however, the Nazi’s had lost patience and confined Junkers under house arrest for a year, during which time he founded the Junkers Research Institute Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung (GmbH is a company license in Germany, similar to an LLC) in Munich, Germany.

…And the Tragic Fall of Hugo Junkers

On his 76th birthday, February 3, 1935, the Nazis visited Hugo Junkers for one last round of “negotiations” to persuade him to give them the rights to his companies. Though there is no official record of how it is known that Hugo Junkers died in his home that day. Very shortly after, his wife Therese ceded all control of the Junkers companies and patents to the Nazis for a tiny fraction of their worth.

On his 76th birthday, February 3, 1935, the Nazis visited Hugo Junkers for one last round of “negotiations” to persuade him to give them the rights to his companies. Though there is no official record of how it is known that Hugo Junkers died in his home that day. Very shortly after, his wife Therese ceded all control of the Junkers companies and patents to the Nazis for a tiny fraction of their worth.

Hugo Junkers was a scholar, a pacifist, and a family man, who contributed innumerable technological advances to aviation and the world at large died a prisoner in his own home, only to have his wife exploited through Nazi fear tactics, and his legacy overrun by the WWII aircraft that still bore his name. Even while being forced into creating military aircraft, Hugo Junkers had focused on protecting the pilots and flight crew from enemy fire, instead of dealing maximum damage to the Allied soldiers. His advances in metallurgy and mechanical engineering have helped to make aviation safer, faster, and more efficient, and his legacy deserves to live on as a mirror of the man he truly was, not as the distorted image the Nazis built using his technology.

Otto Lilienthal: The Glider King

When we look back to the dawn of aviation, we can trace these sweeping changes back to a few pioneers. When we think of the “fathers of flight,” we immediately picture the Wright Brothers. But they weren’t the first to bear that title.

Otto Lilienthal was. Although he never successfully flew a powered plane, he was the first to build and fly winged aircraft. His gliders are the ancestors of today’s airplanes and gliders. And his research on the flight mechanics [Click here to read more…]

Resources:

“Rooted deeply in his own conservative beliefs, Junkers emphasized the concept of struggle as the origin of all life and held a belief in the ‘organic’ structure of society, occasionally expressing anti-Semitic views.

His conservative beliefs were so entrenched that he had no qualms about his company’s involvement in the National Socialist rearmament efforts. He described his first encounter with Hermann Göring at the Berlin Automobile Exhibition with nostalgic words in his diary, and his response to the ABC program (which was related to aircraft production) was more enthusiastic than hesitant. He wrote, “The best forces should be made available for the new project.” Klaus Junkers, who had connections with right-wing circles just a few years earlier, had already joined the SS before 1933.”

As far as whether the Junkers family was paid fairly:

“The publication and application of the amended § 16 were prevented only by the death of Hugo Junkers on February 3, 1935. Since the charge of treason had expired, and a revival of the research institute to the extent envisioned by Junkers was no longer possible, further negotiations on the purchase price for the plants and aircraft patents were brought to a relatively smooth conclusion. The contract for the takeover of the Junkers plants was signed by Keppler and Hugo Junkers’ widow, Therese Junkers, on April 3, 1935. The arbitration panel to determine the purchase price convened on April 30. Its ruling set the purchase price at 7.5 million marks for IFA and 1.5 million marks for Jumo. This was approximately the amount determined by Hugo Junkers’ assessors as the net assets of the plants as of September 30, 1933, and was a total of 4 million marks higher than the price estimated by the assessors commissioned by Keppler. In the case of patents and license fees, the finally agreed price of 3.5 million marks was 1.5 million marks higher than the amount the Reich was still willing to pay in December 1934.”

Source: Lutz Budrass, “Flugzeugindustrie und Luftrüstung in Deutschland 1918-1945”