The American Champion Decathlon: the Sports Car of Singles

By Crista Worthy with Rich Stowell

American Champion Aircraft (ACA) currently produces FAA-certified light aerobatic and utility aircraft for recreational, work, and training use. From the Aeronca, the Champion, and the Bellanca Aircraft Corporations now to ACA, the basic design has proved stable for over 50 years. But don’t think the aircraft haven’t changed: a steady process of refinement and expansion has resulted in a lineage that includes Champs, Challengers, Citabrias, Decathlons, and Scouts. The privately-owned American Champion Aircraft corporation is located in Rochester, Wisconsin, where it manufactures and provides support for its current models.

Mention the word “aerobatics” and many pilots immediately imagine the little Pitts Special biplane. While the Pitts is a superb flying machine, it’s designed for one and only one mission: big time aerobatics! Everything else was a secondary design consideration. For example, it’s anything but comfortable during long trips (not that you can get very far in it with its limited range). It’s blind and twitchy on landing, too.

In contrast, the 8KCAB Decathlons are a line of tame and comfy mounts. The name hints at the Decathlon’s capabilities, being able to do several things reasonably well: dependable spin and aerobatic trainer, decent cross-country performance, fun-yet-docile tailwheel flying. Descended from the Citabria (“Airbatic” spelled backward), the American Champion Decathlon was designed with full-time aerobatics in mind.

A Brief History of the American Champion Decathlon

The Decathlon’s roots go all the way back to the venerable Aeronca Champ. The Champ and competing trainers like the Piper Cub, Luscombe, and Cessna 120 were produced in droves after World War II. By 1951, the market was saturated and production of the Champ ended. (ACA has since resurrected the Champ, manufacturing the 7EC version for the Light Sport market. At a base price of $129,900, they’re available by special order only.)

Bellanca Aircraft Corporation produced four variants of 7-series aircraft throughout the 1960s and 70s known as Citabrias. Then came three variations of 8-series Decathlons, as well as the 8-series Scout. Bellanca went out of business in 1980. Eight years later, ACA acquired Bellanca’s type certificates, and in 1990, new Decathlons were rolling off the assembly line.

Reintroduced with numerous improvements, the American Champion Decathlon was an instant hit. Perhaps the most significant (though not readily apparent) change ACA made to its Decathlons was to replace the traditional wood spars with metal ones. ACA also made metal spar wings available as an upgrade for pre-ACA-era Decathlons.

Common Features of the American Champion Decathlon

At a glance, Decathlons all look pretty much the same: cool paint scheme, semi-symmetrical airfoil, no flaps, tandem seating with solo from the front, tailwheel, skylight, boxy engine cowl, aileron spades, fuel injected aerobatic Lycoming engine, Christen inverted oil system, header fuel tank under the instrument panel, toe brakes. But there are four variants: Decathlon (Standard), Decathlon CS, Super Decathlon, Extreme Decathlon. Standard, CS, and Super Decathlons differ primarily in powerplant and prop combinations: 150 hp with fixed pitch prop; 150 hp with constant speed prop; 180 hp with constant speed prop, respectively. The Extreme is 210 hp with constant speed prop. It also has a different tailplane and aileron design along with clipped wingtips.

Decathlon propellers can be metal or composite, two- or three-bladed. Landing gear can be spring steel or aluminum. Seatbelts can be a traditional latch type or a Hooker five-point assembly. For judging aerobatic lines and angles, some Decathlons may have a metal sighting device attached to the wing struts or tape or grease marks drawn on the side window, while others won’t have any “cheat tech” installed.

Disciples of Flight is honored to have Rich Stowell tell us about his experience with the American Champion Decathlon.

I was inspired to want to try aerobatics after attending the annual airshows at Sussex Airport (KFWN) in New Jersey in the 1970s. I took my first aerobatic lesson soon after earning my private pilot certificate. It was in Super Decathlon N2502Z from Essex County Airport (KCDW) in New Jersey. Forty flight hours later, I was strapped in Super Decathlon N1119E flying above California’s Paso Robles Municipal Airport (KPRB) in my first aerobatic contest.

Thirty years later, I still enjoy flying the Decathlon as much as ever. The logbook shows just under 5,300 hours in 50 different Decathlons. I’ve circled Niagara Falls on the Canadian side in a C-registered Decathlon; conducted live spin training demonstrations in a Decathlon during Sun-n-Fun in Lakeland, Florida; taught rolls in a Decathlon using Mounts Baker and Rainier as visual references.

My day-to-day mount is now N35BY, a 2005 ACA Super Decathlon based at Cascade Airport (U70) in Idaho. Though my wife and I acquired 35BY in 2008, we’ve known the airplane since it was new. In fact, I provided some spin and aerobatic training in it to its first owner. To read more about the story of 35BY, see my blog post here.

PIREP

Super Decathlon 35BY came with a two-bladed composite MT propeller. Max gross weight is 1,950 pounds (compared to 1,800 pounds max in original Bellanca Decathlons). Empty weight is 1,356 pounds. The panel is fairly typical with round gauges but includes an Electronics International CHT/EGT engine analyzer and a King KMD150 GPS. The primary scale on the airspeed indicator is in miles per hour.

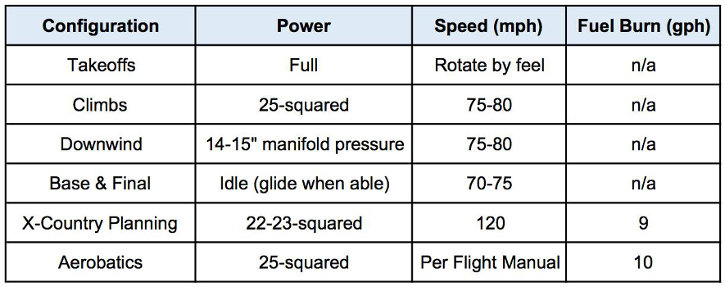

A few of the operating numbers I routinely use:

If the Cessna 172 is the family mini-van, the Super Decathlon is the sports car—lighter and more responsive on the controls. But it’s not a quantum leap in control effectiveness like a Pitts or Extra 300, so most pilots are able to calibrate to the zippier feel of the Decathlon quickly. Transitioning from flying a yoke with the left hand to flying the Decathlon’s stick with the right hand is straightforward (yes, even for left-handers like me). The stick is so natural you’ll wonder why they ever put yokes on airplanes in the first place.

The cockpit is roomier than other tandem tailwheel airplanes, which makes climbing in and out a little easier (though still not what you would call “graceful”). Forward visibility from the front seat is excellent; from the back seat, not so much. The back seat is ideal, though, for developing the peripheral vision and sight picture needed to land a Pitts.

The Decathlon’s elevator trim takes some getting used to. The manual trim knob is located on the left side of the cockpit, near the front seater’s thigh. The knob slides along about a one-foot arc, and the airplane responds immediately to trim inputs. It is possible to perform an entire loop just by manipulating the trim control (it also allows for nice landings in our simulated loss of elevator control scenario). The throttle uses the same type and color knob as the trim and is also located on the left side of the cockpit. A pilot that is new to the Decathlon (or who is overly fatigued) occasionally gets the two controls confused.

Confusing trim and throttle in critical conditions close to the ground has caused some accidents. My advice: Don’t rest your hand on the trim! As soon as you’ve set it where you want it, put your hand back on the throttle.

The Decathlon and its Lycoming powerplant are robust. As long as you fly the airplane in a consistent manner within its approved operating parameters, keep up with routine maintenance, and hangar it, airframe and engine will last and last. Paint (and the fiberglass cowl) will develop cracks over time no matter how flexible it is. Clear tape will prevent them from growing. Reaching engine TBO or beyond should not be a problem either, even with daily training use by conscientious flight schools. If the airplane is used as a spin training platform, it’s a good idea to check the interface where the rudder cables attach to the rudder horn at the tail. The bolts have been known to notch and the holes in the rudder horn to elongate over time and heavy use. As a matter of course, I have those two inexpensive bolts replaced every annual whether they need it or not.

Structurally, the airplane—whether wood or metal spar equipped—will last forever when flown within a +3.5/-2 G environment. If you routinely operate the Decathlon near its +6/-5 design limits, however, expect wear/tear, broken parts/pieces, and operating costs/downtime all to rise exponentially. Poorly executed snap rolls, i.e., trying to fix bad technique by adding more speed and G at entry, will also accelerate wear and tear and might even result in leaky fuel tanks.

To reduce the likelihood of developing cracks in the fuel tanks and to stay within the airplane’s acrobatic weight and balance, the standard spin and aerobatic training fuel load is half-tanks (20 gallons) or less.

Flying the American Champion Decathlon

What can I say? The airplane just feels right. It wants to fly. It’s happy on grass or pavement. It does demand proper tailwheel technique, though compared to other tailwheel airplanes, its behavior during takeoff and landing is more docile.

I prefer a stick-neutral take off whenever conditions permit. This allows the airplane to establish its takeoff attitude naturally (why work so hard?), requiring only a slight squeeze of aft elevator to levitate off the ground. Three-point landings are its bread-and-butter: slow, soft, with a welcoming chirp. Even in crosswinds 45 degrees off the runway at 29 gusting to 32, I’ve never felt the wheel landing to be a “must do” maneuver. Three-point, crosswind-corrected landings work fine in the majority of situations in which pilots might find themselves in the Decathlon. This is due in part to the Decathlon’s weight coupled with its semi-symmetrical airfoil, as well as its good control authority at approach and landing speeds.

35BY is capable of delightful, positive-G aerobatics. Loops, Rolls, Spins, Immelmanns, Hammerheads, Cuban Eights, Barrel Rolls, and other fun combinations. On the negative-G side, it’s a good trainer to introduce pilots to that strange and uncomfortable environment. Inverted stalls, inverted turns, basic one-turn inverted spins, basic negative-G pushes. If you want to delve into anything beyond that, it’s time for the Pitts or Extra.

You can fly inverted continuously for about two minutes before the fuel in the header tank runs out and the engine falters. Rolling upright will recharge a depleted header tank in about a minute while the faltering becomes a smooth running engine again.

Spins in the Decathlon are similar to those in other aerobatics-approved airplanes. Normal upright spins are smooth and steady; normal inverted spins oscillate. Please use NASA Standard spin recovery inputs to recover from spins; hands-off is unreliable in the Decathlon. Some normal upright spin data I’ve recorded:

Rate of rotation over three turns: 130 degrees/second

Rate of descent in 1,000 feet: 4,600 feet per minute

Number of turns in 1,000 feet: 4.5

Altitude loss, one-turn with pullout to level: 600 feet

There’s nothing like perfectly orchestrating the tumbling and twisting of snow covered mountains, lush green farmlands, and deep blue waters from the cockpit of a Decathlon!

Conclusion

There you have it—the American Champion Decathlon can be a tame and comfy recreational airplane, a dependable trainer and a serious aerobatic performer. Being able to choose from among four variations means you can find an American Champion Decathlon tailored to the kind of flying you do. The more you look at all the Decathlons’ abilities, the more you realize what a pleasure they are to own. They’re relatively inexpensive to purchase and maintain, they’re not particularly difficult to learn how to fly and land safely, they’re fairly stable, and they can even do well in the backcountry.

About Co-Author Rich Stowell:

About Co-Author Rich Stowell:

Stowell took his first flying lesson in 1982 and earned his Private Certificate in 1984. He began his career as a full-time instructor in 1987. In 2001, Stowell was designated the country’s first Master CFI-Aerobatics and has served on the Master Instructors LLC Board of since. He is also the 2014 National FAA Safety Team Rep of the Year, the 2006 National Flight Instructor of the Year, and Charter Member of SAFE. Stowell has authored books about Emergency Maneuver Training and Stall/Spin. He has authored dozens of articles, conducted several hundred seminars, scripted numerous videos, and appeared on television and radio programs. He developed the Emergency Maneuver Training program and an Aerobatic Instructor Designation Program and currently teaches in Idaho. Stowell specializes in tailwheel, emergency maneuver, stall/spin awareness and aerobatic training, and can be reached through www.RichStowell.com.

Featured Image by George A. Kounis / www.PilotGetaways.com

I am new to aerobatics and looking for recommendations for my first parachute. Will be flying a 8KCAB. Thanks in advance!