Nathaniel J. Adams and 271 Days of Combat

How many people can say their work has changed the face of their home state? And of those, how many can say they did something that substantially affected world history by saving the life of a future president? Nathaniel J. Adams could have said that. But he preferred action to speeches. His deeds during WWII reveal a young man 100% committed to his comrades and country. And when he returned from battle to his Idaho home, Nat Adams commenced upon an outstanding architectural career, even as he committed himself 100% to his beloved Sally and their future family.

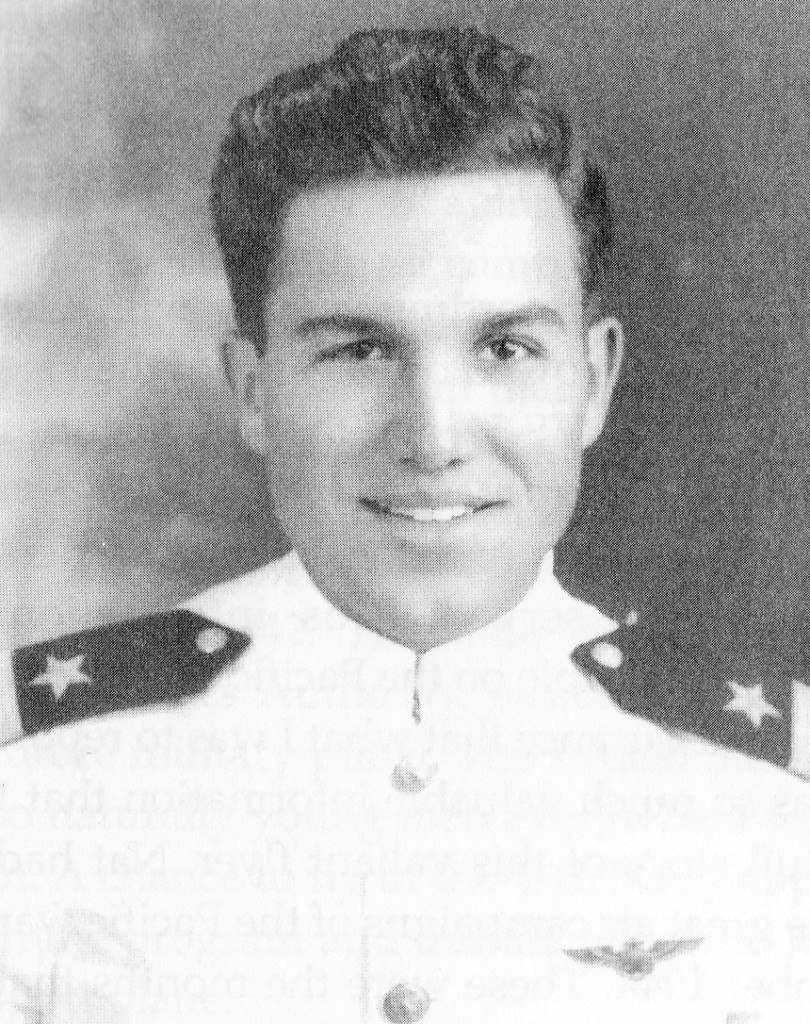

Nat Adams was born July 16, 1921 in Buhl, Idaho. He moved to Boise with his family at age three, graduated from Boise High School, and attended Boise Junior College across the river. Between the river and the college, a single runway hosted a small air company delivering mail. (That small air company eventually grew into United Air Lines.) After the attack on Pearl Harbor the college and the Civil Aeronautics Authority established a program to train future military pilots. Nat was accepted into the program and learned to fly a low-wing Ryan open-cockpit airplane at the little airport. He then enlisted in the U.S. Navy, said good-bye to his family and sweetheart Sally, and set off to earn his Navy “Wings of Gold”. Another cadet nicknamed him “Blackie” for his thick black hair, and so he was known to his squadron throughout the war. Nat qualified as a carrier-based fighter pilot, his first choice, and was sent to Oahu, Hawaii. His new aircraft would be the 2,000-hp Grumman Hellcat, a major upgrade from the Wildcat he had flown previously. The Hellcat, along with the TBM Avenger torpedo bomber, were the two aircraft types largely credited with the air defeat of Japan. After only three hours in the Hellcat, Nat was sent for carrier qualification; a few days later he landed on the USS Monterey as part of Task Force 58, powering across the Pacific toward the Palau Islands. (One of the officers onboard, a Lt. Ford, had been captain of the Michigan football team. Many years later, Gerald Ford became President of the United States.)

Nat’s first combat came on April 30, 1944. Truk, a valuable Japanese base for air and sea operations, had been hit before, and it was time to finish the job. Hit at daylight by other carrier aircraft, Truk’s oil storage tanks were already on fire and spewing black smoke. In a flight of four, Nat dove his Hellcat through a hole in the smoke, his six 50-caliber guns blazing. Braving a continuous rain of ack-ack, the fighters destroyed the facility. Pulling out, he spotted a destroyer in dry-dock, and they blew that apart too. This vital base was now inoperable.

After his tour with the USS Monterey, Nat was ordered to the legendary USS Enterprise on June 21. From June 22–July 5, the carrier launched daily strikes on the Orote peninsula at Guam, to clear the landing area for the Marines. Nat flew directly into fearsome enemy fire every day. On July 14, he was ordered aboard the USS San Jacinto, his home until November 30, 1944. Nat was now a member of fighter squadron VF-51, and joined in the camaraderie with the other pilots. On July 25, Nat was assigned a 150-mile patrol north of the Palau Islands with four fighters and two torpedo planes. After shooting down a Japanese bomber, the group spotted what they thought was a destroyer, but was actually a munitions ship loaded with mines. The American pilots pressed home repeated strafing attacks in the face of heavy return fire, and then Nat again dove in formation behind his comrades toward the ship. Suddenly a mushroom cloud of smoke and shrapnel exploded into his plane, tearing off part of the port aileron and damaging the wing. After Nat regained control, his flight leader Lt. Griffin pulled up alongside. Over the radio he said, “It’s bad Blackie. You’ll never get the plane back on the carrier. Do you think you can keep it under control?” Nat signaled thumbs up. “OK, I’ll try to get you back to the escort destroyer for a water landing. That’s your only chance.” With the aileron gone, his plane would stall and spin before he could slow it to carrier landing speed. But if he landed too fast on the heaving sea, he would cartwheel to certain death. Pulling up along the destroyer USS Healy, Nat skillfully stalled the Hellcat into the water tail first at full power and then cut the engine. Getting out of the pitching plane was difficult, but he managed to swim away and grab a life preserver. For his “outstanding skill, courage and determination” that day, Nat was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

In the meantime, many events, both harrowing and mundane, would transpire: Safely aboard after his successful ditching, the ship’s doctor was surprised to find Nat didn’t even have a scratch; he only needed dry clothes. But on the way to the officer’s dining room, Nat smacked his head on a steel beam. Blood streamed down his face and it was back to sick bay for a patch-up.

Day after day through the summer of 1944, U.S. forces pressed their attacks on islands across the Pacific. 400 miles south of Tokyo lay the island of Chichi Jima. Communication towers crucial to the Japanese Empire were housed within its volcanic rock, protected by a blanket of anti-aircraft guns. On September 2, four Avenger pilots from VT-51 were ordered to penetrate the barrage of flak and knock out the radio towers on Chichi Jima. One of those was a 20-year-old Lt. (jg) George H.W. Bush. Nat and three other Hellcat pilots were to fly cover for the Avengers. Adding to the tension, their carrier would depart immediately after launch to join another attack 1,200 miles away. The pilots would have to carry out their mission and catch her before they ran out of fuel.

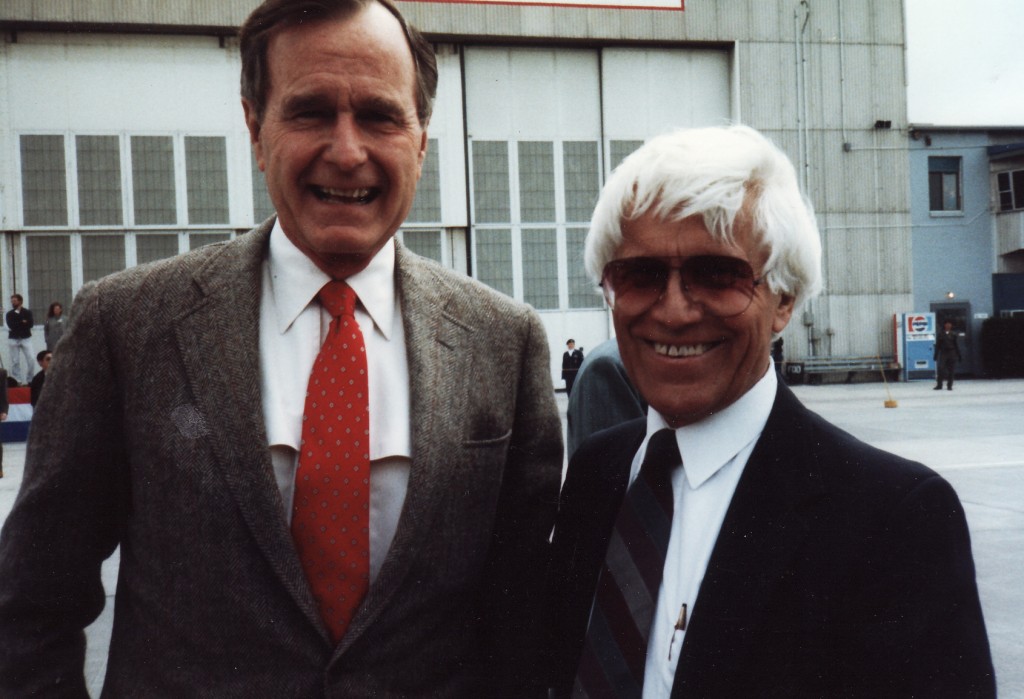

In position over the island, the Avengers dove in pairs through exploding anti-aircraft fire to deliver their bombs. Bush, leader of the second group, nosed over into his dive as the bomb bay doors opened, but then his plane took a fatal hit. He continued the dive and dropped his ton of bombs but Nat could see his engine flame, the fire spreading toward the wing’s fuel tanks. Bush leveled his smoking aircraft and Nat heard him tell his crew to bail out, yelling, “Hit the silk! Hit the silk!” One crew member jumped but his parachute failed to open. Nat saw him fall to his death. The other crew member never responded; he was likely dead from shrapnel. Bush then escaped his stricken plane, which exploded just before he hit the water. Nat watched him inflate his life jacket and get into his little raft. The wind was blowing Bush toward the shoreline just a couple of miles away and a small flotilla of Japanese boats was already in the water, rushing to capture him. Nat and the other Hellcat pilots dove at the boats until they blew them all out of the water. Nat and the other fighters continued to circle the area, keeping the Japanese away for about two hours until a U.S. submarine surfaced and plucked Bush out of the ocean. They then raced toward their carrier, happy they had enough fuel to catch her. Other airmen captured at Chichi Jima were not so lucky as Bush. The Japanese, after interrogating and torturing their prisoners, cut open their chests to reveal the beating heart and heaving lungs of their living victims. As the pilots bled into unconsciousness, their captors decapitated them and finished the ceremony by eating their livers. Over the years, President Bush remembered his squadron mates on numerous occasions. On February 24, 2004 he wrote a letter of thanks to Nat which read, in part, “Dear Blackie….without your covering support I would undoubtedly have been captured, executed and cannibalized. With warm regards to you and yours, George Bush.”

Nat continued flying and fighting through summer into fall, pressing attacks on Peleliu, where 2,000 Americans were later killed over 42 days of fighting. From there it was on to Okinawa where Nat earned an Air Medal by single-handedly blowing up a torpedo boat. In two days the Avengers sank over 50 ships while the fighters of the combined task forces destroyed over 100 aircraft. From October 12–14, Task Force 38, with planes from 16 carriers, made sweeps on Formosa. U.S. aircraft hit ammunition dumps, industrial plants, utility buildings, hangars, and sank ships. The Hellcats primarily targeted airfields, engaging Zeros and braving barrages of anti-aircraft fire. Nat recalled, “Here I was, an adventurous little guy from Boise, Idaho, flying with one of the most powerful striking forces ever assembled. It was unreal.” But the toll was real, and the Americans lost 79 airplanes and 64 airmen over Formosa. Still, the pre-emptive strikes in Okinawa and Formosa saved countless American lives in the soon-to-come Philippine campaign.

From Formosa, Nat’s squadron immediately moved to Luzon, the northern-most island of the Philippines, to participate in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle in world history. For two weeks, the USS San Jacinto remained under sustained alert, even as her pilots made daily raids. One day Nat and two other pilots were attacked by Japanese fighters. The three pilots were credited with shooting down three aircraft, which earned Nat another air medal. After one violent dive, Nat pulled out just in time—his propeller blew plumes of ocean spray into the air.

When Admiral Ozawa’s advancing fleet was located, the pilots of Task Force 38 were sent out at daylight. On October 24 Commander David Campbell (who had shot down nine Japanese planes the day before) along with Commander Hugh Winters, led them into the fight. Ozawa’s ships threw up 2,000-pound projectiles from their 16-inch guns, along with more ack-ack than Nat had ever seen. With the Hellcats covering the Avengers, four aircraft carriers were sunk, forever ending Japan’s ability to launch planes from aircraft carriers. Nat had participated in two engagements that were part of an American victory of historic proportions. He and his comrades were ready for the war to be over. Instead, they were sent back to the Philippines where they disrupted shipping, covered the Avengers (including Bush, who had returned), and shot down fighters and bombers.

On November 14, after enduring particularly heavy flak, Nat returned to the carrier during a major storm. Orbiting the ship in the landing pattern, the LSO repeatedly waved off the fighters as the deck pitched violently. Two aircraft landed so hard their fuselages buckled; they were immediately dumped as wrecks over the fantail. Nat had to make 26 passes before he was allowed to land. Just as he got his “cut” signal from the LSO, the ship pitched up to meet him. Nat recalled, “The Hellcat smacked with such force that it bounced, hit the barrier, spun around, and the left wing took the tails off two parked Avengers. Two medics jumped aboard and took me to sickbay where I stayed for observation for three days.” As the USS San Jacinto sped back toward base, it came under a night attack by Japanese torpedo bombers—fortunately all the torpedoes missed.

Flying into the face of death day after day, Nat survived 271 days of combat during the height of the U.S. conflict in the Pacific. He returned to Boise for his well-earned leave on Christmas Eve. He was later transported to Pearl Harbor to begin his second tour of duty but the Japanese surrender intervened. When Nat returned home, it was with the Distinguished Flying Cross, a WWII Campaign Medal, Pacific Campaign Medal, Asiatic Campaign Medal, another Air Medal, Battle Campaign Medal with Seven Combat Stars, and a Presidential Unit Citation Medal. The city wanted to honor him but Nat politely declined. “I’m no hero”, he said, “The real heroes are all the guys who didn’t come back”.

After returning home, Nat made plans to resume his studies. His father had owned lumberyards, so Nat grew up with an appreciation for building and a love of fine woods. He decided to pursue a degree in Architecture. It was fall and time for school, but he had one more important plan to make. Sally recounts, “One day he said to me, ‘Would you rather get married at Christmas or Spring Break?’ It wasn’t whether; it was just when! I said, ‘Is that a proposal?’ We were married the following spring and lived in Student Housing at the University of Oregon.” During this time, Nat also flew the Hellcat out of Seattle in the Navy Reserves. After graduation, three years’ apprenticeship, and passing the Board Exam, Nat completed a large interior design project for a Wyoming resort. He used the fees to start his own architectural firm in Boise.

As the years passed, Nat and Sally raised their sons Tom and John. The only times the medals, goggles, and leather flying jacket emerged from the basement footlocker were when the boys “played Navy”, running around with them in the yard. Nat was busy building a remarkable career and enjoying life with his family. The medals seemed irrelevant and were largely forgotten after the boys stopped playing with them. As Nat’s staff and reputation grew he began designing large commercial projects. He would often rent a Cessna in Boise, fly to a distant job, waggle his wings over the project site, and have the contractor pick him up after landing nearby. Flying allowed him to keep tabs on construction projects and be back at his desk by noon. Nat sometimes worked around-the-clock to get jobs done on time and under budget. Nat and Sally counted dozens of successful Idahoans as their personal friends. At one event “potato billionaire” J.R. Simplot pulled Nat aside and said, “You’ve been around awhile; you must know something. Why don’t you design my house?” Nat Adams projects include the Boise State University stadium and physical education complex (built on the site of the airstrip where Nat originally learned to fly), First Security Bank, Ste. Chapelle Winery, St. Thomas and All Saints Episcopal Churches, and over 700 other projects in Idaho and across the Northwest, a number of which received American Institute of Architects (A.I.A.) design awards. He served as President of the Idaho Chapter of the A.I.A., President of the Historic Preservation Commission for Boise, and served on numerous other Boards including St. Luke’s Regional Medical Center, the Idaho Aviation Hall of Fame, the Sawtooth Society, and Downtown Rotary Club. He gave guest lectures at Nampa’s Warhawk Museum, sharing his WWII experiences with hundreds of Idaho youth. For his contributions, and for Sally’s Art in Schools programs and success in persuading leaders of over 75 Idaho corporations to purchase and display Idaho artworks in their offices, Nat and Sally together were awarded the Lifetime Achievement Governor’s Award for the Arts in 2004. The Idaho Historical Society retains Nat’s architectural tracings and other papers.

“Nat flew his Porsche, he didn’t drive it”, Sally says, until she told him how it scared her. After that, he never drove fast with her in the car again. “He was committed to me 100%. You know, of 36 men in that squadron, not one of them got divorced.” Nat and Sally saw Nat’s old squadron members at Navy reunions and at Bush’s inauguration and other events. “They still called him Blackie even after his hair turned prematurely snow-white. At the christening of the G. H. W. Bush aircraft carrier, the admirals all said how honored they were to meet him. They were in awe of his wartime seat-of-the-pants flying off those little carriers and yet he was so humble”.

After a short illness in 2007, Nat returned home from the hospital. His family gathered at home, and his sons found the forgotten old footlocker in the basement. Inside were combat photos, a Presidential Citation, his airplane’s leather cushion, a slew of medals, and not one, but two Distinguished Flying Crosses. Why he was awarded the second Flying Cross isn’t known. Nat died a few days later. All Saints Episcopal Church filled to overflowing for his funeral; hundreds more simply stood outside in the parking lot to pay their respects. Two officers stood in salute during his entire interment ceremony, followed by a missing man formation flyover.

As Americans, we literally owe the existence of our free country to the bravery and sacrifice of the veterans of WWII. When we search for role models, these are the people we should emulate and teach our children about. And when we speak of “their sacrifice”, we should remember that sacrifice was made over and over, each day in combat, one terrifying moment at a time—a commitment made anew each day.

Nat’s legacy lives on in his wife Sally, a woman of exuberance and charm. Their sons and grandchildren lead interesting lives in business, the arts, and even architecture, living out the promise written on Nat’s headstone, “CAVU”. Ceiling and visibility unlimited.

Nat Adams’ medals, citations, logs, and other materials are on display at Warhawk Air Museum in Nampa, Idaho.

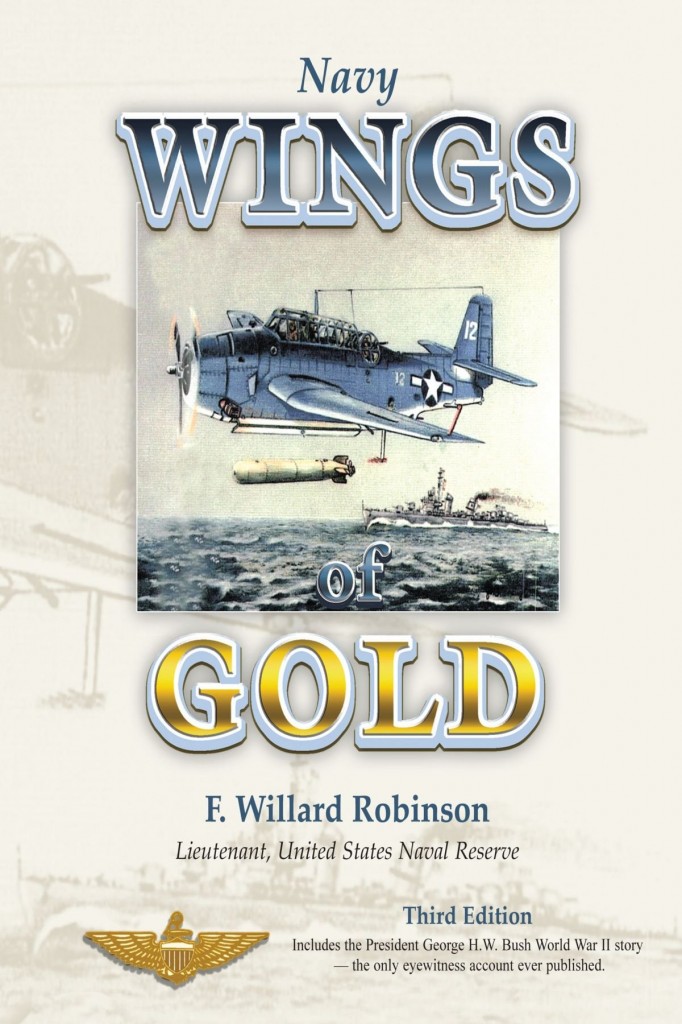

Read more incredible first-hand accounts from WWII pilots in “Navy Wings of Gold” by F.W. Robinson, available in our Pilot Shop.

Leave a Reply