Some plane concepts, like parasite fighters, never really take off.

During the early days of military aviation, the effective range of most aircraft was quite limited, meaning that aircraft with ground attack or bombing missions were frequently without fighter escort and thus vulnerable to aerial attack. In this same time period, aerostats were in common use for military purposes and thought to be especially vulnerable to enemy fighters. From this threat arose the concept of parasite fighters, small fighters that could launch from an airship or bomber for short range defense. Plagued by logistical and technical issues, parasite fighters never made it to mainstream military use despite experimentation from 1915 through the 1950s.

Not So Promising Early Results

The idea of a bomber or dirigible carrying several small fighter craft for defense and attack sounded quite appealing during World War I. Raids by enemy dirigibles were particularly troublesome. Before customized parasite fighters were designed, existing airframes were used. Early fighter planes were light, had low stall speeds, and had limited logistical requirements, meaning that they’d be able to successfully gain enough lift after detachment from the mothership. The British were the first to pioneer the technique, using a BE2.C reconnaissance plane attached to the bottom of an airship by a metal bracket which could also retrieve it after its missions. This resulted in a catastrophic crash which destroyed both craft. The British would later successfully launch a Bristol Scout from a Porte Baby flying boat, deciding that airship launches were too high risk. Nonplussed by the failure of the British, the US Army experimented with using a JN-4 fighter and one of their airships, successfully launching it but not attempting an aerial recovery.

The Interwar Period

After their initial successful experiment, the US military wouldn’t return to the idea of parasite fighters until 1930, while developing new air warfare doctrines. The British experimented sparsely in the interwar period, conducting two successful airship-launch tests in 1925 before showing good sense and abandoning the idea completely and permanently, favoring fully functional interceptor aircraft launched from traditional airfields which could be distributed throughout their territory.

The US continued to experiment with parasite fighters using their airships. After testing the first functional aerial recovery system in 1930, the Navy requested two airships to be built specifically to function as motherships and furnished them with reconnaissance planes. In a stark contrast with the efforts of the previous and also the subsequent 20 years, there were no major accidents resulting from the recovery system, and aerial recovery was the norm. Despite this, the lack of a war to fight starved the parasite fighter program of efficacy testing, preventing it from growing. Research and trials continued until the airships were destroyed separately by unrelated events.

During this same time period, the Soviet Union developed their own parasite fighter system, deciding to mount I-4 fighters onto a TB-1 heavy bomber. Interestingly, the Soviets considered the mothership concept loosely, planning for some fighters of the mothership’s complement to dock with it in the air after taking off separately. The mothership would provide fuel to its fighter craft, and extend their effective range by as much as 80%.

The advantage that the Soviets saw in the parasite fighter concept was in dive bombing: heavier bombs could be used by smaller fighter craft if they didn’t have to take off while carrying the extra weight themselves. The mothership would take off carrying a couple of fighters, attach the stragglers who took off separately, then fly to the combat zone where the fighters could be dispatched on dive bombing or, if necessary, interception duties. Eventually, small quantities of fighters and motherships were produced, totaling 18 aircraft.

The Soviet parasite fighter concept was the high water mark of the idea, surpassing all prior attempts in both depth of investigation and actual efficacy. The final product of the Soviet trials was known as the Zveno-SPB, which utilized a TB-3 heavy bomber and two I-16 Type 5 fighters. Unlike all other countries who experimented with parasite fighters, the Soviets would be the only ones to use them effectively in war.

World War 2 and the Cold War

During the early phase of World War 2, the Soviets successfully attacked stationary targets and enemy ground forces in Romania using the Zveno-SPB system’s fighters dozens of times, though aerial reattachment wasn’t used under combat conditions. Deployment of the Zveno-SPB ended with the advent of the Soviet airforce’s heavy losses during 1942, though no motherships or fighter craft were lost to enemy fire. Aside from scattered one-off trials of parasite fighters by Germany and kamikaze parasites by Japan, the retirement of the Zveno-SPB marked the end of effective use of parasite fighters.

Though the ICBM-free early phases of the Cold War meant that protection of bombers was more important than ever, only the US reopened their trials of parasite fighters, trialing several different concepts. Project Tip Tow sought to mount F-84 fighters onto a B-29 bomber and included provisions for aerial reattachment after launch. Ultimately, the project was ended when a catastrophic aerial attachment caused the loss of the fighter and the mothership with all crew. Notice a trend yet?

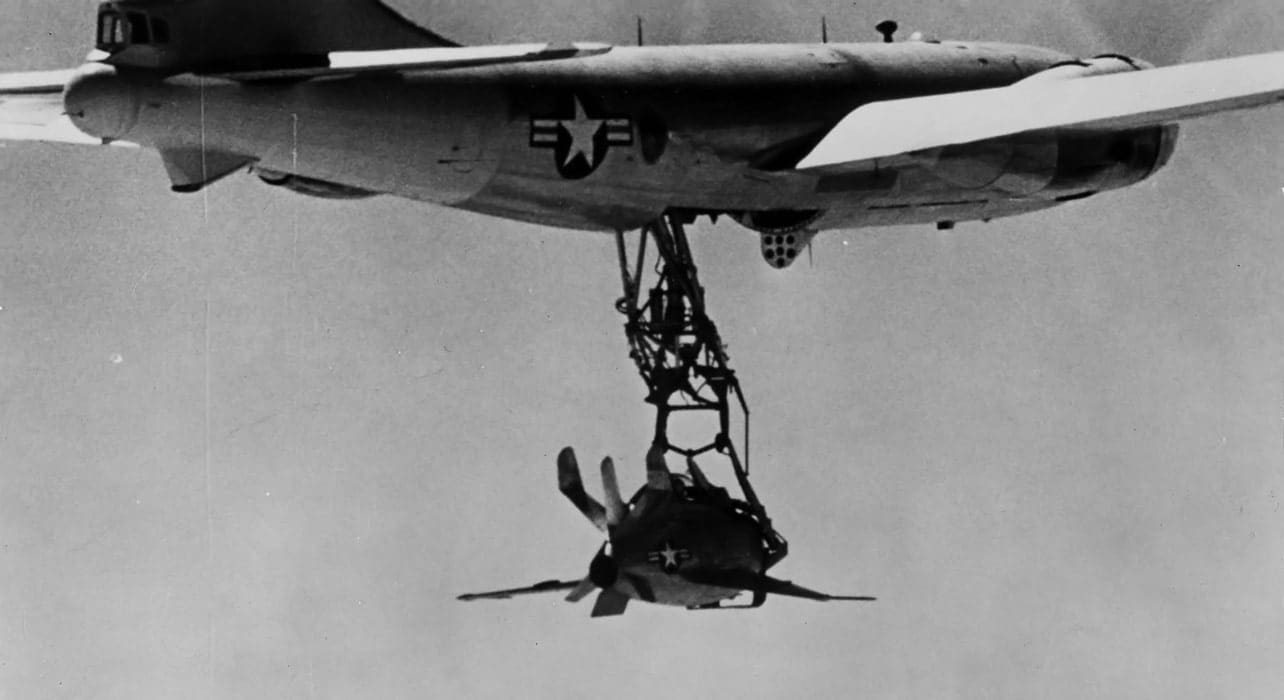

The US wasn’t done with parasite fighters just yet, though. New projects were proposed and implemented. Perhaps the most notable of these renewed efforts resulted in the XF-85 Goblin, a feisty midget jet. The Goblin was intended to be deployed from the bomb bay of a B-36, fighting off enemies before returning home. Predictably, the Goblin was never able to keep up with the fighter aircraft that it would be opposing in the event of combat use and was canned expediently.

A-10 Warthog: The Close Air Support Specialist

The A-10 Warthog. Combat ground troops love it and Air Force leaders hate it, favoring the new F-35. What does that say about the current state of military affairs? But the A-10 has a record that can’t be contested, a record going back to the first Gulf War, and that’s the reason that its retirement keeps getting delayed.

The A-10 Warthog. Combat ground troops love it and Air Force leaders hate it, favoring the new F-35. What does that say about the current state of military affairs? But the A-10 has a record that can’t be contested, a record going back to the first Gulf War, and that’s the reason that its retirement keeps getting delayed.

The A-10 Thunderbolt II is really the only true aircraft built solely for Close Air Support (CAS) in the U.S. military. [Click here to read more…]

No More Parasites

The rise of aerial refueling seemed to kill off the parasite fighter concept definitively, with no nation other than the USSR able to make the concept work as intended. Rather than carry escorts, interceptors could simply accompany bombers, meeting with refueling craft as needed. Aerial refueling also proved to be much safer for all involved.

In many ways, parasite fighters were always understood to be speculative and experimental and never threatened to break through into mainstream military aviation. That didn’t stop a handful of nations from trying, though. The biggest takeaway is that some ideas simply can’t take flight in a way that’s safe and effective.

Featured Image: XF-85 Goblin attached to mothership, courtesy of the USAF

Leave a Reply