In the Navy, November 1942

Franklin Willard “Robbie” Robinson, Jr. lived a remarkable life.

His personal achievements, military service, and other contributions place him among Idaho’s distinguished citizens. Born September 11, 1918, Robbie grew up dividing his time between his parents’ Long Beach city home and their mountain ranch north of Los Angeles.

During the Depression you needed plenty of sweat and perhaps a little daring to get what you wanted. After his freshman year at the University of Southern California (USC), Robbie offered to ride a new Raleigh 3-speed across the country as an advertising gimmick if Raleigh would let him keep the bike. Robbie set off in August of 1937 from Ann Arbor, Michigan, with a few clothes, a blanket, and no training. He had just donated blood at the Ann Arbor hospital for the $25 he needed to buy food, so he was weak and “only” made 100 miles the first day. By nightfall, he collapsed onto his blanket beside the road, too tired to sleep. But youth and drive compensated for the lack of preparation. Robbie’s strength returned and he crossed the prairies, climbed the Rockies, and finally crossed the deserts in 110-degree-heat to arrive in Long Beach after 14 ½ days and 2,500 miles. The journey was covered in the Long Beach Press-Telegram.

The following summer, Robbie and his friend James Dyer rode their bikes from Long Beach to the remote red-rock hamlet of Escalante, Utah. They hiked slot canyons, found Indian ruins, got lost, and eventually stumbled into the tiny Mormon community of Boulder. Dyer returned to Long Beach, but Robbie took a job as a farmhand in exchange for three squares a day. At summer’s end he traded his rifle for a horse and saddle. The farmer also helped him catch a wild horse off land made famous by author Zane Grey, which he tamed for use as a pack horse before returning to Long Beach via horseback.

Adventure called again the following summer. Robbie and his friend James journeyed from Seattle to Alaska in an 18-ft. sailboat. Inexperienced seamen, they fought navigational errors and storms but arrived in Ketchikan after six weeks. The year was 1939; Japan controlled much of the Far East and German panzer tanks had begun streaming into Poland. James joined the U.S. Coast Guard, while Robbie continued to Fairbanks and enrolled at the University of Alaska.

That fall, a red Waco biplane landed at Fairbanks’ dirt strip, flown by Army Air Force Lt. Richard E. Ragle, who brought an offer by the U.S. government: The Civil Aeronautics Authority would select 20 candidates, based on academic standing and physical conditioning. After ground and flight training, those who passed the flight check would receive a Limited Commercial pilot license. Robbie immediately signed up and was selected. In the early 1940 Alaskan winter, he began flight training in a Taylor Cub on skis. A few months later, he was scheduled for his flight test. If he passed, he would become the first government-trained pilot certified in the Territory of Alaska. A newsman from the local radio station arrived with the examiner. Lt. Ragle and the newsman flew behind Robbie and the examiner, so the newsman could describe the exam. The flight and Robbie’s success earning his certificate were reported that evening on the news.

After working his way to San Francisco aboard a U.S. transport ship, Robbie watched as two disassembled P-40s were loaded onboard for the return trip, the first combat fighters sent to Alaska. Back at USC, he began his senior year while also working as a typist for Douglas Aircraft and renting a Piper Cub on weekends to stay current.

On Sunday December 7, 1941, Robbie was having breakfast at his parent’s home when the news came that Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japanese. America was at war. The next day, Robbie drove to the Long Beach Naval Air Station to apply for Navy flight training. After passing the physical exam he was ordered to Elimination Training and given the few weeks necessary to complete Economics degree at USC.

Daily ground school and flights in yellow N2N biplanes followed. The pressure was high; washouts were an almost daily occurrence. The graduates, including Robbie, were sent to Corpus Christie as aviation cadets for the summer of 1942. Hours of marching, blinker code, and rows of N2S Stearman biwing trainers awaited them. The open field lacked a runway; cadets simply took off into the wind. Dozens of cadets would be in the air at all times, honing the maneuvers, night, formation, and instrument skills they would use in combat. During this time, the Battle of Midway took place. In this crucial battle, four Japanese carriers were sunk, stopping their westward advance. American torpedo bombers flew their aircraft directly toward enemy ships and into the line of fire 200 ft. above the ocean, before releasing their torpedoes. Of Torpedo Squadron 8, only one plane and two men, out of an initial 24 planes and 72 men, survived. The need for new torpedo pilots was dire.

Soon thereafter, a senior naval officer addressed the Corpus Christie cadets. The time had come for them to choose their advanced training: multi-engine, dive-bombers, fighters, or a new Torpedo Squadron 13. Robbie was one of 30 cadets who stepped forward to join this first specialized torpedo class. Flying the SNJ, the Navy’s designation for the AT-6, Robbie completed advanced training and received his Navy “Wings of Gold” as an Ensign USNR in November 1942.

From there he was ordered to Opa Locka, Florida, for Operational Training, and then to Norfolk, Virginia in January 1943 for qualification as a U.S. Naval Carrier Pilot. Bad weather prevented further flying; his light Florida uniform was inadequate in the freezing temperatures. As they waited, Robbie spent time with Bob Koontz, another Corpus Christie grad. Bob had just married his high school sweetheart three weeks prior. Finally, Bob and Robbie found their names posted on the flight schedule. They checked out parachutes and found their assigned aircraft. No service personnel were around to prepare the planes. Robbie meticulously scraped the snow, and then a layer of ice, off his airplane, as he’d been taught in Alaska. Twelve pilots took off, headed for a British carrier off the coast. To qualify, each man had to successfully complete eight landings. Opening your canopy was a requirement on final approach, and Robbie could scarcely control his airplane, he was shaking so violently from the cold. After his third landing, he noticed Bob Koontz was in front of him. As Bob turned final, his plane stalled. He tried to jump out but got caught on the canopy. Robbie watched in horror as Bob went down with his plane.

That was the third fatality of the day.

Two other pilots had been launched before enough pressure had built up in the catapult for them to achieve flying speed; those pilots fell into the sea and were run over by the ship. 25% of the young men who’d flown out for their final qualification, after all they had been through so far, never made it back that day.

Robbie completed his landings and then had to notify Bob’s young wife of his death. Robbie was given a two-week leave after which he was to report for duty. He accompanied Bob’s widow on a long, sorrowful journey to Nebraska via train, and then continued his lonely way home to Long Beach, deep in thought.

Life or death could be so arbitrary; life was such a temporary gift.

Toward the end of his leave, after much thought and prayer, he walked into the bank where his high school sweetheart Joan Larrimer worked and invited her to dinner. At dinner he proposed, saying, “I’m leaving tomorrow to join my squadron; don’t answer me now.” They hadn’t seen each other in two years. After arriving in Seattle he called her and Joan said, “Yes, I will marry you. I do love you and I think I always have.” Like so many other young wives of this time, she would experience much happiness, but also difficulties most of us cannot imagine.

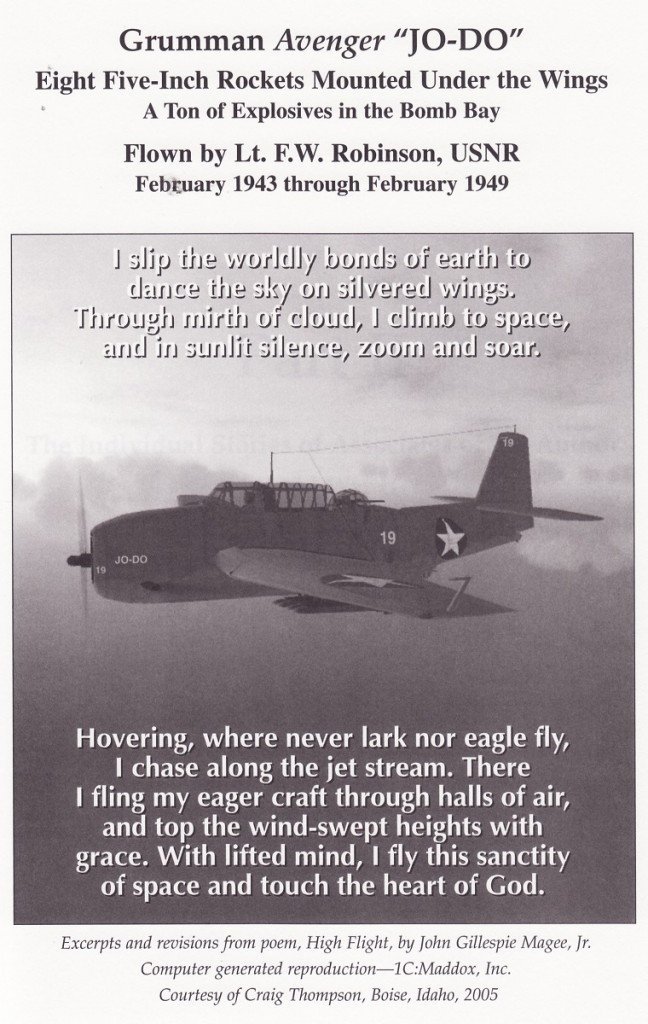

Robbie trained in his TBM Avenger, “Jo-Do”. Over unlit California deserts, Squadron VC-7 flew night formation simulated torpedo runs. In the fall of 1943, the squadron was given a top-secret assignment, working with Caltech scientists on the first air-to-ground missiles. On December 3, 1943, at the Inyokern Naval Air station, eight rockets were hung beneath the wings of his Avenger. Robbie fired up the 2,000-hp radial engine, gained altitude, and dove at 200 mph toward the target, firing the first air-to-ground missiles in naval history. The eight charged heads blasted the target to oblivion. Now the American torpedo bombers would be able to launch the same firepower as a full salvo of shells from a light cruiser—a tremendous increase.

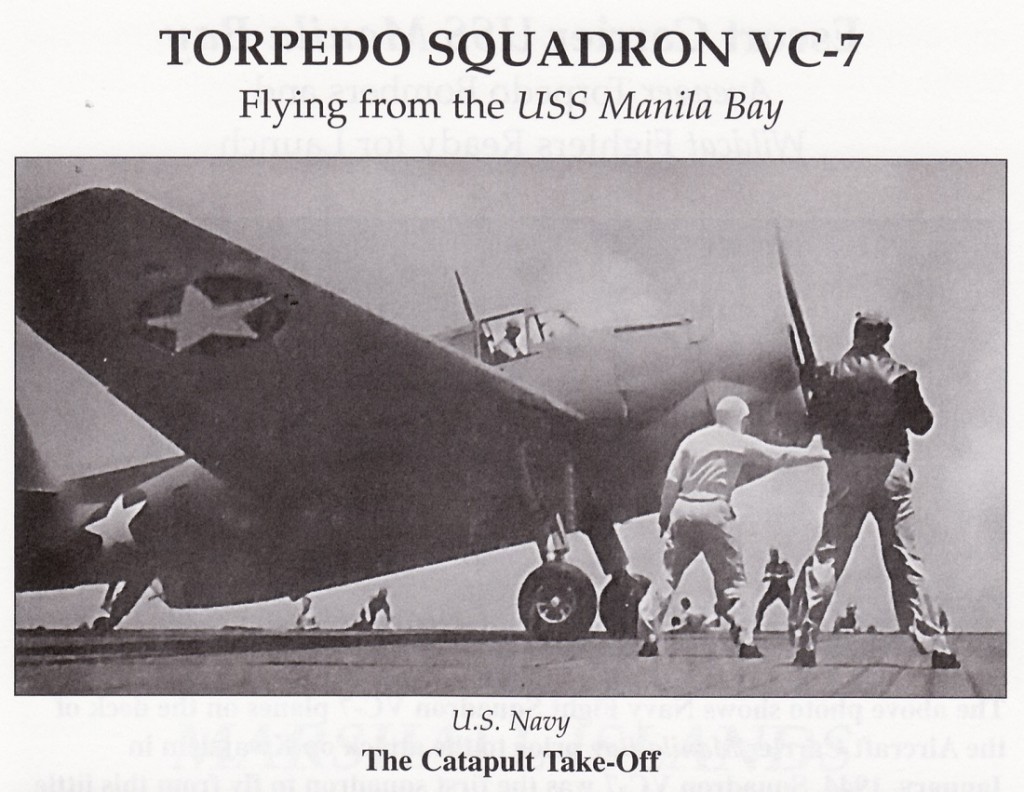

The war was taking a terrible toll. Off Tarawa atoll, a Japanese submarine had torpedoed the escort carrier USS Liscombe Bay, killing 644 men and nearly all the pilots onboard. In January 1944 the Squadron VC-7 departed San Diego aboard the little escort carrier USS Manila Bay. After a stop in Pearl Harbor, where the USS Arizona and over a thousand soldiers lay entombed, the fleet sailed toward the Marshall Islands. The Avenger pilots flew submarine patrol. Admiral Nimitz had begun a huge and sustained attack on the Marshalls. Neutralizing the outer air bases with air strikes, the fleet focused on Kwajalein Island. Each Avenger was launched with four 500-lb bombs and eight missiles. In one attack, Lt. Arnold Erickson, Robbie’s best man at his wedding, fired his missiles and then his engine went silent. Beginning his emergency checklist, he realized the rpms were still normal and he had instantly gained 4,000 feet of altitude, but he still could not hear his engine. A gray mushroom cloud appeared from below; Erickson had hit a munitions depot and the blast temporarily deafened him, pushed his plane up, and filled its underside with shrapnel; he landed safely.

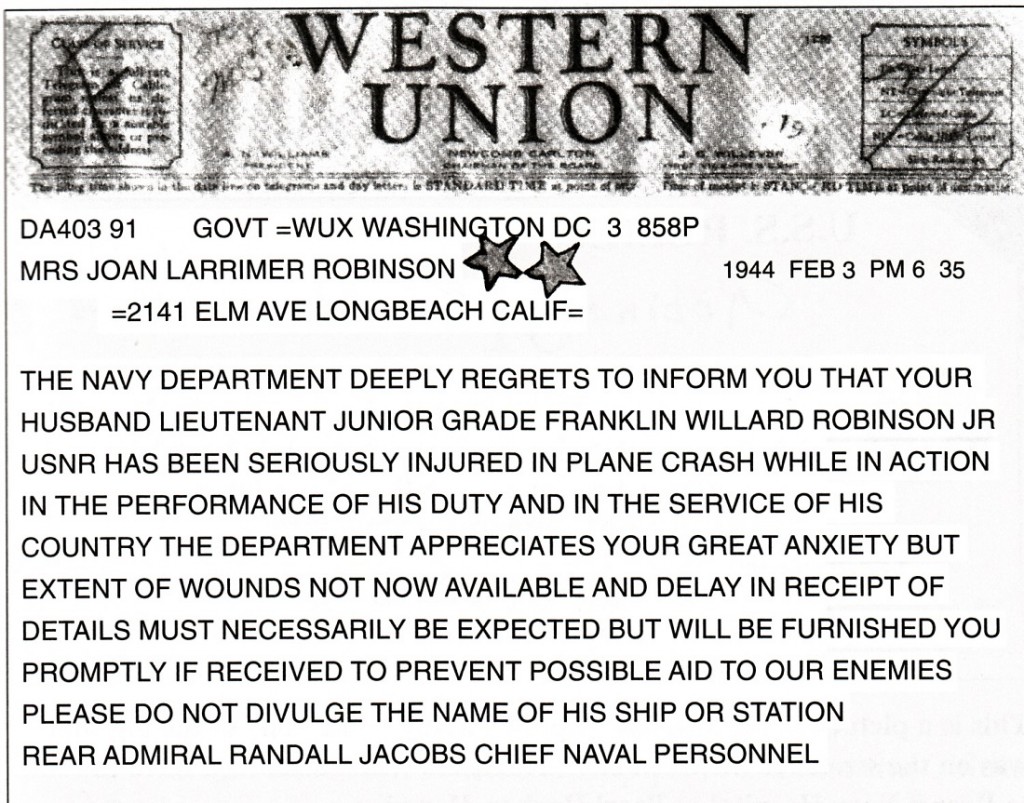

Occasionally an Avenger would be ordered on a remote search mission. In early February 1944, Robbie was given a search mission in a new TBM-3E, a plane he had never flown, rather than his old “Jo-Do”. His radioman, George Driesbach, Jr., and gunner, Harold Eckert, climbed aboard the plane, loaded with a ton of bombs and a full load of rockets and fuel. After the catapult launch, the plane was uncharacteristically sluggish and nearly plunged into the ocean before recovering. It seemed this new model TBM was heavier. They found no enemy activity during their five-hour flight and returned with all armaments still onboard. On downwind at full power at the prescribed ninety knots, the plane suddenly lurched and dove into the sea, exploding on contact. Then each 500-lb torpex blew in its turn, sending walls of water and flashes of light into the air. Robbie was tossed and pummeled, but somehow inflated his life vest as the water grew still. His crewmates were gone, a pain he has borne every day since. Soon a destroyer approached and Robbie on the loudspeaker: “For God’s sake, there’s a man alive out there! Full reverse! Get a line out!” As the ship veered, he grabbed the life preserver and was instantly towed under by the reverse action of the giant propeller. Somehow he resurfaced. A seaman jumped overboard and secured the line around him as he lost consciousness.

During the night he awoke in an officer’s cabin. His right leg was ripped open, shrapnel was imbedded near the base of his spine, and he suffered multiple blast injuries. Bleeding under the skin discolored his entire body. An officer entered. “You’ll be all right. I’m going to keep you right here in my bunk until we can make contact with a hospital ship. Welcome to our destroyer. I’m Abraham Lincoln, commanding officer, and you are on the USS Caldwell.”

After a week Robbie was transferred to the USS Relief, where he saw the results of battle for the first time. Like other Pacific islands held by the Japanese, Kwajalein was riddled with tunnels and fortified bunkers. The Japanese were fighting to the last man and the hospital ship became crowded with gravely wounded American soldiers. Robbie was moved out onto the deck and watched as the dead were buried at sea. After a month the ship docked at Pearl Harbor and Robbie was moved to a hospital; he could not walk yet or write. A sympathetic nurse wrote to Joan; it had been nearly two months since she’d been notified that her husband was “seriously injured” and she had no further idea of his whereabouts or condition. Several weeks later, Admiral Chester Nimitz entered the hospital room, speaking to each wounded man. He sat beside Robbie and asked how he was wounded. “It was just an operational accident, sir,” Robbie replied. “Well, Lieutenant, you were out there doing your job, and I know it’s dangerous work. The country and I thank you for being there. God bless you.” This remained one of Robbie’s treasured memories. At the time, he felt like a failure. The encouragement from this powerful man helped Robbie get back on track. Eventually he walked again, but limited knee flexibility prevented him from shipboard duty. Instead, nearly a year after the crash, he was ordered back to the California desert as a test pilot to validate aircraft as ready for operational service after they had been repaired, and to investigate training crashes. He served there until after the Japanese surrender.

After the war, like others of the “Greatest Generation”, Robinson’s efforts focused on completing his education, establishing a career, and raising a family, guided in all pursuits by his unshakable faith in God. He earned his M.S. in Education and Ed.D. with majors in administration and philosophy, from the University of California. Over his career, Dr. Robinson served on numerous state and regional education boards and committees. In 1959 he began his 16-year tenure as Principal of Beverly Hills High School. Under his leadership the school implemented a model individualized educational program that received national recognition. During the Vietnam War, when his students threatened to emulate the violent protests occurring in schools around the country, Dr. Robinson was able to defuse the tension and instead allow students to express themselves in constructive ways, challenges he wrote about in his memoir, Beverly Hills Principal.

While at Beverly, Dr. Robinson pursued post-doctoral studies in theology and counseling, administration, and ethics at Fuller Seminary. In 1976 he accepted an offer to direct Laity Lodge and Christian Men, Inc., and moved his family to Kerrville, Texas and then Austin, where he served as Minister of Education at Westlake Hills Presbyterian Church.

In 1986 he and Joan retired to the family ranch north of Los Angeles before moving to Boise, Idaho, where son Tri had founded Vineyard Boise and served as Lead Pastor. Having spent decades informally researching his family’s genealogy, Robinson then penned a two-volume family history, tracing his and Joan’s roots back as far as the 1300s.

On March 4, 2013, as friends congratulated the couple on their 70th anniversary Robbie commented, “I think this marriage is going to work out.”

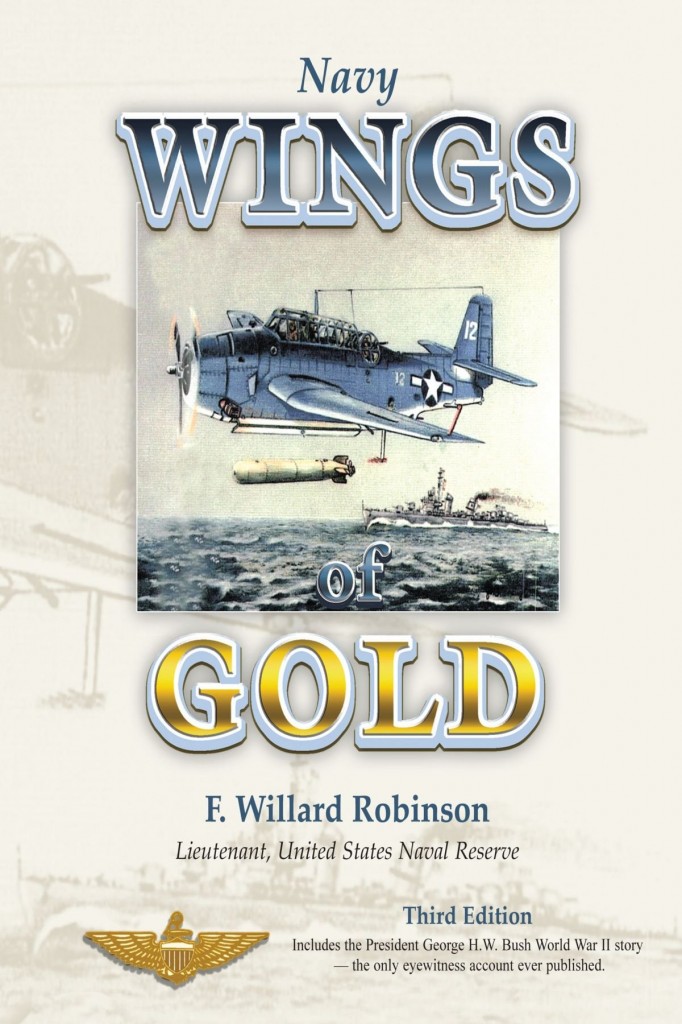

His final book, Navy Wings of Gold, is a gripping collection of first-person accounts of WWII aerial battles as told by numerous decorated pilots, and includes the only published eyewitness account of the rescue of Lt. George H.W. Bush, after he was shot down over the Pacific.

Franklin Willard “Robbie” Robinson Jr. died Saturday, the 25th of October, in Boise, of Alzheimer’s Disease. He was 96.

Robinson closed his book with the words, “There is awe. Life is a gift and a great mystery. I lift my hands in wonder and thanksgiving for the assured hope of eternal adventure.”

(Robbie Robinson, left, and fellow World War 2 Navy pilot Nat Adams.)

F. W. Robinson’s book ‘Navy Wings of Gold’ can be purchased here. It is filled with harrowing first-hand accounts of WWII aerial battles, as told by the pilots who lived to tell about them.

2 Comments