There has, and will always be, debate about a magic number of pilot hours required for certain types of flying and ratings.

The Minnesota blizzard was a sharp contrast to the Cancun sunshine we’d just left a few hours earlier. Since I’d flown the first leg, it was my first officer’s turn to fly back and land at MSP. ATIS had informed us that the weather was just barely above minimums, but braking action was still good. A few airplanes had initiated missed approaches, so we knew we had a good challenge ahead. To add to the joy, there was a gusty crosswind that was going to test all of our skills. Since it was a long flight for a Boeing 727-200, we didn’t have a lot of extra fuel to play around with either.

As we were being vectored to the outer marker, I turned to my copilot and asked if he was all set for the approach. I wanted to make sure he was comfortable with the challenges ahead and that his head was in the game in case we had to go missed. He had a serious look on his face, but when I asked if he was comfortable shooting the approach, he turned to me and said, “Yeah, this is great! I’ve never actually shot an approach to minimums in real life…” My first reaction was disbelief and then I wanted to say, “Okay, I have the aircraft” and take over the flying, but copilots are future captains and since I’d flown with him for almost a month, I knew this copilot had great airmanship skills. Part of the captain’s job is getting first officers their experience. He had a stabilized approach going, we had full anti-ice on, he had pitch and power perfect, so we continued on the approach—I just paid a bit more attention. He shot a perfect approach and we broke out at minimums, on perfect airspeed and glideslope, and he nailed the landing. “That was perfect. Nice job!” I said. He just looked at me with a flushed face and said, “That was awesome.” It was. It didn’t matter that this was his first approach to minimums. He had the airmanship skills to do it a thousand hours ago, he just hadn’t had the chance.

After we got to the gate, I turned to him and asked, “Okay, tell me how the heck you have a couple thousand hours, you’re a first officer on a commercial airliner, and you’ve never flown an actual approach to minimums (they’ve all been simulated).” “Well, I grew up in southern California. I always flew in the southwestern part of the U.S., so I just never had to do an actual approach to minimums, especially in the snow…”

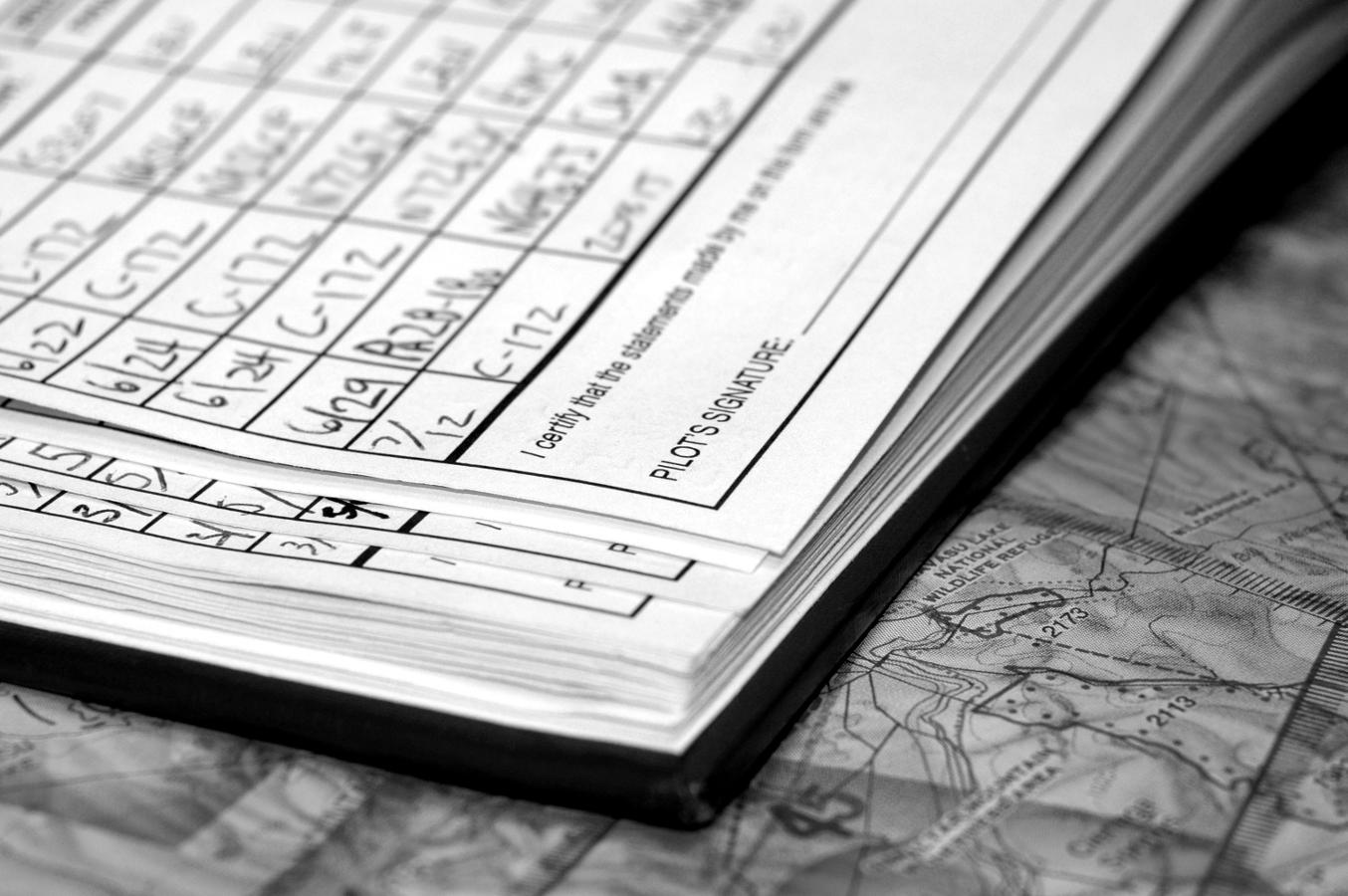

There has, and will always be, debate about a magic number of hours required for certain types of flying and ratings. At the heart of the question is; how do you correlate ability with the number of hours in the logbook? The answer is: you don’t. Just because you have 1500 hours in your logbook doesn’t mean you’re instantly a great pilot. There are as many variables to each person’s character, ability and experience as there are people. However, the bar has to be set somewhere and the bar has been placed there for a reason.

The aviation industry learns from its experience and its tragedies. There is a certain expectation that during those hours to reach a goal, the pilot will be exposed to a variety of experiences creating a basis for airmanship skills, but there will always be something they haven’t done. Sitting in a full motion simulator is not the same as the real thing. Neither is watching an autopilot do all the work, yet the hours add up the same. There are many airline pilots who fly international, for example, that don’t get a lot of stick time, but it’s balanced with their enormous brain data base of experience. It’s about having a constant balance of experience, training and knowledge. If you’re a low time pilot, then the balance is tipped towards inexperience. The more you fly, and the more experiences in your logbook, the more balanced a pilot’s skillset becomes. If a pilot is hired with zero time for an airline, and spends the majority of their time in simulators, or enroute with the autopilot on, there is not an opportunity to find that balance. It doesn’t mean they aren’t great pilots, it’s just that they don’t have a variety of experiences to draw from should an unusual situation present itself.

The recent Germanwings tragedy was an anomaly, but it revealed that the copilot had been primarily a glider pilot before getting hired by Lufthansa in September 2013. Eighteen months after getting hired, he still only had 630 hours total time at the time of the crash. This triggered some debate about how he could be in that seat when pilots in the U.S. can’t get a job at the majors until they have at least 1500 hours—and most have thousands more than that. Would those hours have made a difference? No. It wouldn’t have mattered how many hours he had if his intention was to kill a plane full of people. However, if this particular copilot had gone through the rigors of what U.S. pilots currently go through, he may have been filtered out of the pilot herd before he was in control of 150 lives. The cold hard fact is that with 630 hours, he would not have been at the controls of a U.S. commercial airliner, whether he deserved it or not, or if he was an excellent pilot or not. This exact set of circumstances could not have happened on a U.S. carrier.

U.S. pilots, for the most part, have to apply and interview for a variety of flying jobs before they ever think about applying to the commercial airlines. They have to be mentally tough and have a deep passion and focus to get their aviation jobs. This process also makes great pilots by learning to fly in a variety of challenging conditions, going through several interviews, and being exposed to different environments. This doesn’t mean foreign pilots are any less skilled, but getting hired into an airliner without good basic airmanship skills doesn’t give pilots the experience to draw upon. Most U.S. pilots start at the bottom and work their way up. Flight instructing, military, charter, corporate, air ambulance, banner towing, crop dusting, glider towing, etc. You have to really want to be a pilot to make it through this long and intense initiation. The first officer who had never flown an approach to minimums had been a charter pilot. He had earned great basic airmanship skills. It didn’t matter that this was his first actual approach, his basis of experience made sure he did a great job—even though his first “real” approach was with 173 passengers onboard. His total hours didn’t mean he had experienced it all, it just meant he had a good skillset to draw from. He had a balanced logbook.

I know many military pilots who have very few flight hours, but those hours are intense and backed by a ground school that makes sure these pilots are the best around. Their hours aren’t the same as everyone else, but the hours still read the same on a logbook page. If you have the opportunity to start flying jets earlier in your career, you’ll cover more miles, but have less hours than someone flying piston multiengine aircraft. So, who is more competent? It will always depend on the individual and the variety of experience.

There are pilots with just a few hundred hours that have more poise and competence than other pilots with thousands of hours. There are thousands of examples and variables and that’s the point. While there is not necessarily a direct correlation between hours in the logbook and skill, we have to have a measurement and a minimum while keeping in mind that it’s not the hours; it’s the type of experience you’re supposed to get during those minimum hours. It’s part of an important filtering process to refine the individual to their peak pilot performance.

Re: Your article “Logbook Magic Numbers: Connecting Pilot Hours with Ability”

Interesting article, but as a 20,000 hours plus pilot myself, if a fair weather pilot attains the minimum total of 1500 hours, and by his/her own circumstances they have never had the opportunity to log experience in weather less than VFR, then I would say we should re-evaluate if that pilot meets the “experience” factor necessary for the operation, e.g., Colgan Air crash in Buffalo, which coincidentally was the linchpin factor in the minimum requirements being raised to 1500 hours. Perhaps it should be mandated to actually log full-up procedures to minimums (my company does; but not all do apparently), even when it’s CAVU, not augmented by the autopilot, or auto-throttles. Just my thoughts, but you cannot check that box and move on without first attaining the “actual” experience in “those” conditions; perhaps those individuals should either document this experience, but without which, they should be scheduled to conduct this operation with a check pilot until their logbook reflects a required amount of actual conditions to these minimums. Obviously I am referring to the SIC pilot. The PIC should never be placed in that position without first checking those boxes as a SIC. Thank you.