Bessie Coleman’s Impact on Woman and Minority Roles in Early Aviation Was Immeasurable.

No better loved Queen in history had come from more humble beginnings than Queen Bess, the woman who changed the landscape of aviation, and race relations, in the United States, paving the path toward equality by encouraging women and minorities to pursue their dreams.

Bessie Coleman’s Early Life

Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman, who would later be known by her admiring fans as Queen Bess, was born on January 26, 1892, to George, a part-Cherokee sharecropper, and his wife Susan, where she would be the tenth of thirteen Coleman children. George and Susan were both children of slaves and were illiterate. The family lived in a one-roomed, dirt-floored cabin in Atlanta, Texas, where they stayed until Bessie was two years old. The family then moved to Waxahachie, Texas where he bought a quarter-acre parcel of land and built a three-bedroom house. Soon after, two more baby girls were born.

Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman, who would later be known by her admiring fans as Queen Bess, was born on January 26, 1892, to George, a part-Cherokee sharecropper, and his wife Susan, where she would be the tenth of thirteen Coleman children. George and Susan were both children of slaves and were illiterate. The family lived in a one-roomed, dirt-floored cabin in Atlanta, Texas, where they stayed until Bessie was two years old. The family then moved to Waxahachie, Texas where he bought a quarter-acre parcel of land and built a three-bedroom house. Soon after, two more baby girls were born.

Bessie’s mother, Susan, and two of her older brothers went to work to provide for the destitute family, Susan as a cook/housemaid, and the boys likely worked in the fields, when such work was available. At age six, Bessie began attending school in Waxahachie and taking care of the younger children in the evenings. Early in the morning, Bessie would set out on her four-mile hike to the one-room, segregated school where she would spend the next 8 years learning.

After she finished her schoolwork, Bessie would read to her mother and siblings, establishing herself as a pillar of the Coleman family at a very young age. Each year, life was put on hold as everyone who was physically able was sent to the fields for the cotton harvest; schools were closed, church activities were postponed, and entire families spent long days hunched over the fields in the baking sun.

In 1901, things took a tough turn when George Coleman left his family and returned to Oklahoma, then known primarily as “Indian Territory,” to try and find better employment opportunities. Susan and the children, however, did not go with him.

Money Was Always a Problem

At age 12, Bessie Coleman was accepted into the Missionary Baptist Church, and until she was 18, Bessie worked as a laundress, saving her pay until she could afford to attend university at the Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University (now called the Langston University) in Langston, Oklahoma. Unfortunately, Bessie was only able to complete a year of schooling before exhausting her funds and moving home.

In 1916 Bessie moved in with two of her older brothers in Chicago, Illinois, where she worked as a manicurist at the White Sox Barber Shop in the South Side of Chicago. At this time, World War I soldiers were still finding their way home, and trying to rejoin society after the tragedy and horrifying events they saw in the foxholes and battlefields of Europe. Her two brothers also served overseas, and between them and her veteran customers, Bessie was infected by the call of adventure, more specifically, flight.

As siblings tend to do, one of Bessie’s brothers was teasing her about how much better French women are than American women, part of the reality of gender inequality in America at the turn of the century. Her mind thrilled by pilot’s stories flying over the wonders and oceans of the world, combined with her brothers joking, inspired her to take action and change her life. Determined to be a force of equality in the world of aviation, Bessie then decided she would eventually open a school for young, black aviators, and picked up a second job in a chili parlor to save money even faster.

Friends in High Places

One of the customers at the barber shop she worked at, Robert Abbott, publisher of the Chicago Defender (the nation’s largest African American weekly newspaper), was a huge ally for Bessie along her path to fame. After deciding that she would become the first black female aviator in history, Bessie set out to find a flight instructor, but it was no easy task. Most American instructors wouldn’t bother with a woman pilot, let alone a minority woman. With defeat beginning to look like the only option, Abbott encouraged Bessie to move abroad and pursue flight training elsewhere. The French aren’t racists, Abbott told her, and the globally renowned Caudron Brother’s School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France accepted female applicants.

With a goal in sight, Bessie put her nose to the grindstone and worked hard during the day to save up money while she attended the Berlitz School in Chicago at night to learn French. Bessie, the opportunist that she was, recognized that her job as a manicurist in Chicago put her in touch with some of the most powerful African-American community leaders at the time, and used those connections to sponsor her trip. Jesse Binga, creator of the first bank in Chicago owned by an African-American, and Robert Abbott alongside the Chicago Defender pitched in to support Bessie’s dreams financially.

As she taxied towards the runway, some of her competitors doubted Jacqueline Cochran’s plane would make it into the air. Not because she lacked skill or experience – just one year earlier, she had placed second in the same race. No, it was because of the sheer weight of fuel she was carrying. Unwilling to lose time refueling, Jackie Cochran had told her engineers to add more fuel tanks to her Seversky SEV-S2. And so her plane was bulging with added fuel capacity. But with 541 gallons of fuel on board, it was far from certain that she would be able to leave the ground. [Click here to read more…]

Bessie Coleman’s Time in Europe – Allons-y à Paris!

After she had saved up enough money and learned a comfortable amount of French, Bessie Coleman was off to Paris. On November 20, 1920, she arrived overseas, where she traveled to the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation. Bessie would spend countless hours in a rickety Nieuport 82, a 27’ biplane that was prone to mechanical failure. As the only non-white student in her class, Bessie would get the worst equipment and likely the least time with the instructor, but she wouldn’t let racism deter her: she had come too far. During the seven months she studied for her license, she watched a classmate die in a plane accident, which she called a “terrible shock,” but not even this could stop Bessie from pursuing her dreams.

I refused to take no for an answer.

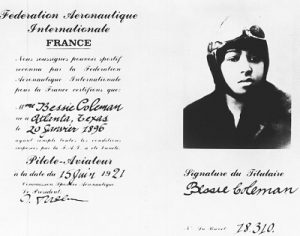

On June 15, 1921, Bessie became the first black woman, and the first woman of Native American descent (her father was half Cherokee) to earn an international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. With one of many recognitions of her talent and determination under her belt, Bessie hopped back across the pond and arrived in New York in September of that year, where she was surprised to run into a considerable amount of press coverage. Bessie had cultivated an interest in becoming a stunt pilot, captivated by the thrill of life-threatening aerial stunts. However, supposedly due to her inexperience, but more likely due to close-mindedness about her race and gender, no one would hire Bessie as a stunt pilot, so she returned to France to hone her skills.

On June 15, 1921, Bessie became the first black woman, and the first woman of Native American descent (her father was half Cherokee) to earn an international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. With one of many recognitions of her talent and determination under her belt, Bessie hopped back across the pond and arrived in New York in September of that year, where she was surprised to run into a considerable amount of press coverage. Bessie had cultivated an interest in becoming a stunt pilot, captivated by the thrill of life-threatening aerial stunts. However, supposedly due to her inexperience, but more likely due to close-mindedness about her race and gender, no one would hire Bessie as a stunt pilot, so she returned to France to hone her skills.

Fine-Tuning Her Flight Skills in Europe

Beginning February 1922, Bessie Coleman spent two months with a French ace pilot, studying outside of Paris before traveling across Europe to hone her aviation skills any way she could. One of her first stops was Germany, where she met Anthony Fokker, a German ace pilot and aviation pioneer in his own right, and toured the Fokker Corporation factory, where she received additional flight training by one of Fokker’s chief pilots. Now that she knew what made planes tick and how to handle them, Bessie was determined to return to America. Let the nay-sayers come, she thought. She had the skills and experience to prove herself worthy of any pilot job available, and her dream was to become an aerial stunt pilot.

Bessie Coleman Returns to America

Bessie’s return to America turned her into a media sensation. She was singlehandedly introducing aviation to an entire culture of people and proving that women and minorities were equally skilled and capable in every field of work. Bessie wanted to immediately begin touring as a stunt pilot, but though she was gaining the public’s attention, she hadn’t captured it enough yet. As a publicity event, Bessie scheduled her first air show on September 3, 1922, at Curtiss Field. Glenn Curtiss, aviation pioneer, lifetime rival of the Wright Brothers and business partner of the Master Birdman, Lincoln Beachey, lent Bessie a plane of his own for the show.

Lincoln experienced phenomenal amounts of fame and recognition in his later years, but no one who knew him in childhood would have guessed. He was a small, rotund little boy, awkward and bullied by his peers. He wasn’t athletic or particularly academic, but his unstoppable passion for aviation was visible from a young age. He grew up on Mission Street in San Francisco with his older brother Hillery, close enough to ride his bike to Fillmore Hill (one of the steepest hills in San Francisco [Click here to read more…]

After WWI, surplus Curtiss JN-4 biplanes, which were originally used as Army training planes, were being sold cheaply to the American public, which in turn helped make the Barnstorming Era possible. The Jenny has become one of the most famous planes flown in WWI, with an estimated 95% of all military student pilots having trained in one. It was a twin-seat dual-control biplane, powered by a tractor propeller and a 90 horsepower Curtiss OX-5 V8 engine, with a top speed of 75mph and a ceiling of 6,500’. Bessie would appear before the public in a Curtiss Jenny many times throughout her career.

Bessie Coleman’s First Airshow

The airshow was an event to honor the veterans of the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment and was highly publicized by Bessie’s old friends at the Chicago Defender. The event would feature the “World’s Greatest Woman Flier,” according to the headlines of the Defender, in addition to eight other American stunt pilots, and the Black Eagle, a Trinidad-born parachutist named Hubert Julian. Over 3,000 people attended the event, including local dignitaries, to enjoy her “heart-thrilling stunts.” It was a success!

The loop-the-loops, barrel rolls, and pull-up-at-the-last-second dives thrilled the audience, and when Bessie’s formidable skills combined with her natural beauty and eloquence, the public fell in love, especially when she would tell tall tales of her aerial exploits, exaggerating her already impressive stunts in a charismatic way. As a result, the African-American press outlets across the country referred to this amazing young woman as Queen Bess. On the other hand, white-run newspapers would aim a critical gaze upon her opportunist nature and flamboyant attitude.

After the great media success of the first show, Bessie, and her Jenny traveled across the country, performing at airshows for her adoring fans, of all skin colors. Queen Bess was a powerful advocate for equality and refused to perform at segregated venues. During her years touring, Bessie would also speak at public events at schools and libraries to encourage women and African-Americans to pursue aviation, which was a blossoming industry full of opportunity.

Barnstorming: A Countrywide Obsession

Bessie Coleman was one of the pioneering barnstormers of the Roaring Twenties, where talented stunt pilots traveled around the country in flying circuses, performing at exhibitions and even selling plane rides. Barnstorming, which newspapers claimed was founded on bravado and “one-upmanship” got its name because most large plots of land available to land on in that time were farms, and crowds would storm in from every direction to watch the spectacle. The loops, rolls, spins, and even more theatric stunts such as wing-walking (having a passenger or copilot walk along the wing of a plane in-flight) captured the attention of traveling aviation enthusiasts and rural townspeople alike.

Finally after a year of barnstorming, Bessie had saved enough money through her performances to buy her own plane in 1923. On February 22, 1923, on her way to her first West Coast airshow, Bessie’s new plane stalled in midair, sending her plummeting to the ground. The plane was destroyed. Bessie was hospitalized for three months with a broken leg and multiple broken ribs.

Tell them as soon as I can walk, I’ll fly!

The following year and a half would be spent trying to find financial backers that would allow her to continue performing and eventually buy another plane. With the help and persuasion of two fellow churchgoers from a Missionary Baptist Church in Orlando, Florida, Bessie opened a beauty shop, whose profits would financially support her aviation career.

During that year, Bessie was offered a starring role in a film called Shadow and Sunshine produced by the African American Seminole Film Producing Company. It seemed as though things were finally going her way; after a crash that destroyed her new plane and inflicted serious injuries, the money and good publicity she would gain from acting would surely support her dream of opening a flight school for young black “fliers.” Bessie was disgusted when she found out the character she would play would appear as homeless and destitute in the film’s opening scene, finding it an insult to African-American actors and actresses who were strictly limited to demeaning roles in film as slaves or savages. Putting her pride ahead of her wallet, Queen Bess stepped away from the film.

Clearly … [Bessie’s] walking off the movie set was a statement of principle. Opportunist though she was about her career, she was never an opportunist about race. She had no intention of perpetuating the derogatory image most whites had of most blacks. –Doris Rich

Bessie Coleman’s Final Show

By 1926, Bessie Coleman had saved up and bought a used Army-surplus Curtiss JN-4, the plane she flew at her first airshow in back in Long Island. In a letter to one of her sisters, Bessie gleefully wrote that after the final payment on the plane was made, and the profits from her performances cashed, she would finally have enough money to open her school for young African-American aviators. Bessie rode the train into Orlando, while her mechanic and publicity agent, William Wills, picked up the plane from Dallas, Texas and flew it to Orlando, Florida in preparation for an upcoming airshow benefit for the Jacksonville Negro Welfare League.

On a recent trip to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, I stopped into the Ninety-Nines Museum, a museum dedicated to the history of female pilots, for a tour with museum director Denise Neil-Binion. She is a part-time employee with the museum amongst other volunteers with a passion for preserving women’s history in aviation. Neil-Binion had many stories to share – from the first women gaining her wings all the way to present-day leaders paving the way for girls in the future. [Click here to read more…]

The plane was so mistreated and poorly-maintained, William had to stop and work on the plane three times on the roughly three or four-hour flight. On April 30, 1926, William and Bessie were in the Jenny, flying around the exhibition grounds: William was flying so that Bessie could examine the grounds and determine the best location for the event (she would be jumping out of the plane with a parachute), unbuckling her seat belt and leaning over the side to get a better view.

It was then that the treacherous Jenny bucked and dove, suffering from disastrous mechanical failures only 1,000 feet above the ground. Suddenly, the plane flipped on its back and Bessie Coleman was thrown to the ground, where she died on impact. William failed to regain control of the plane, which hurtled toward the ground, killing him immediately.

T he plane was engulfed in a fiery explosion, leaving only limited evidence to determine the cause of the crash. It was tentatively determined that a loose wrench was tumbling about the plane and jammed itself into a gear box. No matter the cause, April 30, 1929, marked a national tragedy which broke the heart of thousands.

he plane was engulfed in a fiery explosion, leaving only limited evidence to determine the cause of the crash. It was tentatively determined that a loose wrench was tumbling about the plane and jammed itself into a gear box. No matter the cause, April 30, 1929, marked a national tragedy which broke the heart of thousands.

A Passion That Rose Above Race, Gender, and Poverty

Due to the powerful bond so many people and cities felt with the small, charismatic Queen Bess, three separate funerals were held in Jacksonville, Orlando, and Chicago. Between the three of them, over 15,000 fans came to pay their respects to the young woman who changed the face of aviation and encouraged desegregation and education for all races and genders. As a young girl, Bessie would comfort her stressed and overworked mother by saying, don’t worry, “I’m going to amount to something” one day. If only she had known what an impact that would be.

I decided blacks should not have to experience the difficulties I had faced, so I decided to open a flying school and teach other black women to fly. If I can create the minimum of my plans and desires, there shall be no regrets. The air is the only place free from prejudice.

Though Bessie was never able to realize her dreams in life, her legacy carried on inside many others who shouldered her burden, including Lieutenant William J. Powell. Powell said that because of Bessie Coleman, a generation of African-Americans “have overcome the barriers within ourselves and dared to dream.” He would go on to write a novel and create the Bessie Coleman Aero Club to continue with her passion of introducing aviation to both the men and women of the African-American community.

Leave a Reply