The Unusual Life of the First Aerial Stuntman Began and Ended at the Base of Fillmore Hill

Early Life on Mission Street, San Francisco, CA

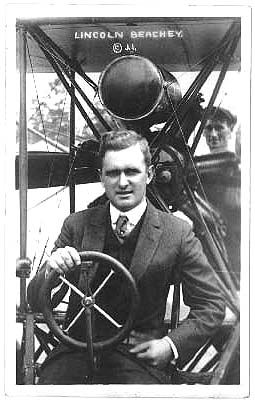

Lincoln J. Beachey was born in San Francisco on March 3, 1887. His father William Clement Beachey, born in 1847, served in the military during the Civil War as a Musician in Co. G, 183rd Ohio Infantry, and grew up in Lebanon, Ohio before moving to San Francisco in 1893 with his wife and Lincoln’s mother, Emma “Amy” Webb, who was born in Alabama in 1864. His birth records were lost in the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake and resulting fire, along with most census records, and so to this day, no one knows what the “J” in Lincoln J. Beachey stands for. After pouring through family trees and ancestry records, I was able to form a hypothesis in regards to his middle name, but it is a stretch at best. Lincoln had an uncle named John W. Drake (who married his father’s sister, Amanda), as well as an uncle named Hillery. Lincoln’s older brother was named Hillery after his uncle, and so I believe that in a similar tradition, Lincoln’s namesake may be his uncle, John. Speculation aside, statistics weigh in favor of his name truly being Lincoln John Beachey due to the sheer popularity of the name John throughout American history.

Lincoln experienced phenomenal amounts of fame and recognition in his later years, but no one who knew him in childhood would have guessed. He was a small, rotund little boy, awkward and bullied by his peers. He wasn’t athletic or particularly academic, but his unstoppable passion for aviation was visible from a young age. He grew up on Mission Street in San Francisco with his older brother Hillery, close enough to ride his bike to Fillmore Hill (one of the steepest hills in San Francisco, of which there are many) and launch himself off it with no brakes, reveling in the short air-time his dangerous game allotted him.

Blinded from his time in the service, William Beachey was unable to support his family, forcing his young boys to find jobs at the fairly young, though not unheard of, age of 13. By that time, Lincoln had acquired the necessary equipment and expertise to open his own bicycle repair shop, which gradually evolved into a motorcycle and engine repair shop as his knowledge and interest in mechanics grew. His lifelong love of flying inspired him to incorporate what he’d learned repairing bikes and engines with the very primitive balloon technology that was popular at the turn of the century. By this time (1900), William was moved to a home for disabled veterans in Yountville, California, situated in the scenic heart of wine country, leaving the two young boys in the care of their mother, Emma.

Bigger, Better, Faster, More Agile: Evolution of the Beachey Dirigible

His passion for flying led him to follow in his brother’s footsteps, and pursue a position working for Thomas Scott Baldwin, a pioneering balloonist. Between Lincoln’s experience with machinery and Baldwin’s experience with balloons, they created the California Arrow, a dirigible powered by a 7-HP Hercules motorcycle engine manufactured by Glenn Curtiss, an aviation pioneer and eternal rival of the Wright Brothers. Lincoln’s first step toward becoming a pilot was the Arrow’s first flight on August 3, 1904, at Idora Park in Oakland, California. Unfortunately, the slow-moving and clumsy dirigible didn’t offer the thrill Lincoln yearned for, even after creating a much faster, more aerodynamic version called the Beachey-Baldwin. Lincoln continued to hone the design as the years went by, and by 1910, Lincoln had engineered racing airships.

In 1906, Lincoln decided to build his own airship from scratch. He traveled east to Toledo where he met aerial exhibitionist Augustus Roy Knabenshue, and together, using a Curtiss engine, a hand-sewn silk gas bag, and a wooden gondola, they did just that. Luna Park, an amusement park in Pittsburgh, PA was interested in using their dirigible for an attraction, and so by the end of the year, Lincoln had signed a contract agreeing to pilot their aerial spectacle. Lincoln’s pride, buoyed by the adoration of his fans at Luna Park and his own formidable self-confidence, decided to ship his dirigible to Washington, where he flew it around the Washington Monument and onto the lawn of the White House. A born thespian, Lincoln proudly marched inside and demanded to see the President, who unfortunately wasn’t home. However, the First Lady, Mrs. Roosevelt was impressed and charmed with this surprise, and soon after Lincoln had airshows booked all across the country.

With the money he earned during his time as a dirigible pilot, Lincoln was able to ask for his sweetheart’s hand in marriage in 1906. May “Minnie” Wyatt was a “buxom,” healthy young lass from North Carolina, and though their marriage would be cut short, it was reportedly a happy and supportive relationship.

In the next year or so, Lincoln set off for New York City, where he intended to fly his dirigible between the early skyscrapers and gather the attention of the bustling streets below. Unfortunately for him, the dirigible wasn’t as nimble as he thought and he smashed the contraption against a building in lower Manhattan, which sent him tumbling into the East River below. Lincoln was fished out of the frigid water safely, but his dirigible sustained some damage.

The 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field featured Lincoln piloting his Beachey-Knabenshue Racing Airship, affectionately referred to as the Rubber Cow due to its bulbous and bulky shape, during a race only 100’ off the ground. Lincoln knew that airplanes were stealing the limelight he so longed for, and was heard remarking to a friend, “Boy, our racket is dead!” as airplanes raced overhead to the cheers and whistles of the crowd. Meanwhile, his older brother was staying one step ahead by beginning to pilot fixed wing airplanes at the same meet. More than slightly jealous, Lincoln demanded a job as a pilot as well, citing his vast and impressive piloting skills, and was turned down. Instead, he was offered a job as a mechanic.

During his time as an aviation mechanic, Beachey reportedly would sleep in a tent near the aviation warehouse and creep into the hangars before dawn to fly the planes in secret. Slowly, Beachey taught himself the basics of flight.

Lincoln J. Beachey’s Dramatic Entrance into the World of Aviation

The 1911 Los Angeles International Air Meet brought Lincoln the break he’d been waiting for. No more patching holes in rubber dirigibles, he’d finally reached the big leagues. While working as a mechanic at the airshow, the star pilot was suddenly injured, and Beachey was able to talk his way into the cockpit. With only limited experience and absolutely zero fear, Beachey immediately took off straight into the air, reaching an altitude of 3,000’ feet before suddenly, the engine stopped. The biplane dropped quickly, spinning itself into the feared death spiral.

In this early era of aviation, the death spiral was an inescapably horrific way to die. Other pilots had tried turning against the spin, which makes logical sense but was unsuccessful, or even tried to aim up and hope to catch the breeze and ride it to safety, which led to disastrous results. No one knew what was running through Lincoln’s head so far above the crowds, but miraculously he decided to turn into the spiral and point the nose of his plane down, an idea most pilots of the time would brush off as a way to get yourself quickly killed.

Whether it was luck or a hidden talent for physics, Lincoln eased the plane into a slow spiral glide all the way to the field below, where he emerged safe and victorious. After what could have easily been a near-death experience, Lincoln reportedly claimed he could now feel the airplane as naturally as part of his own body. After repairing the plane, Lincoln immediately shot back up into the sky and attempted his spiral move 11 more times to prove it was a reliable method, thus giving the awestruck spectators their first glimpse of the infamous Dip of Death.

The Beginning of a Record-Breaking, Award-Winning Career in Aerobatics

By the end of the year, Lincoln had become the star of the Curtiss Exhibition Team, an aerial stunt group founded by the aforementioned aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. Only six months after Lincoln set foot in a cockpit for the first time, he attempted a never-before-seen feat that would make “Beachey” a household name.

The United States-Canadian Carnival based out of Buffalo, NY offered $1,000 to the first person to fly an aeroplane over Niagara Falls. When adjusted for inflation, the prize offered to the first Niagara Falls Daredevil would be nearly $25,000 in today’s economy, which is no small potatoes. Naturally, Lincoln jumped at the chance. His need for stardom and his obsession with being the first and the best at all things aviation would have compelled him to attempt the death-defying stunt even without a monetary prize: the 150,000 spectators chanting “Beachey, Beachey!” was enough for him.

So, on June 27, 1911, Lincoln became the first aviator to ever fly over Niagara Falls, but his passion for theatrics wouldn’t let him stop there. Dressed in what would become his classic get-up, a pinstripe suit with a high collar, a fancy tie, and golf cap turned backwards, Lincoln arrived in a light rain, and dove over the falls from a height of 2,000’ and plummeted towards the water, pulling up with only 35’ between his plane and the churning rapids. As reported by a local newspaper,

Down along the line of the gorge, high over the upper steel arch, Beachey soared, and then, turning back, he hovered over Victoria Park, sailing about until suddenly dipping his machine down, down, down, between the rocky cliffs, he sped like lightning under the arch of the great steel bridge. A tremendous cheer from an admiring multitude nearly drowned the roar of the falls, so intense was the appreciation and admiration. –Plain Dealers Leased Wire, 1911

After Lincoln had dipped to the surface of the roiling spume below, sailing above the crowds, hoisted high by their buoyant jubilation, he landed soaking wet but safe, and admitted to closing his eyes mid-flight:

It was the most exciting trip of my life. I shut my eyes as I flew toward the arch, for into my face the spray cloud of the waterfall was driven as I descended into the gorge. I was fearful that I might strike, but they tell me I took it in a beautiful manner. I am glad not to have disappointed such an appreciative crowd.

Later that same year, Lincoln won many more awards for his stunts, including racing a speeding train and even touched his wheels on the roof of the carriages! Around that time, he also set a new altitude record by filling his tanks with fuel and climbing until he ran out of gas. For nearly two hours he climbed before he ran out of fuel, then he entered into a controlled spiral and glided safely to the ground where he nearly fell out of the plane, so frozen and stiff from exposure. The planes barograph showed that he had reached a height of 11, 578’, which set a new world altitude record.

First Class Aviator, First Class Mischief Maker

Lincoln’s enthusiasm for danger and adventure continued to blossom as he won race after race, effortlessly snatching prize after prize, and yet he never ceased to have fun with flying. On days when he wasn’t risking his life, Lincoln would tease and play tricks on unsuspecting citizens below. Reportedly, Lincoln would fly over ballgames and drop oranges, tricking the ballplayers into trying to catch the hurtling fruits. On February 19, 1912, a reporter from the Morning Oregonian caught the spectacle and reported, “two Oakland ballplayers tried today to catch oranges dropped from an aeroplane flying at an altitude of 550 feet….Neither succeeded.”

Soon after, Lincoln went to Curtiss demanding a plane with advanced fluid mechanics that would allow him to fly upside-down. It was a goal of his to be the first aviator to successfully complete a loop the loop, a never-before-seen aerobatic maneuver which is defined by a pilot pulling the plane up vertically, and continuing around in a circle until he is facing the same direction he started at, and then doing it again, thus “looping the loop.” Curtiss refused to build such a plane, certain he would be sending the young pilot to his death, and so Lincoln stormed out, quitting the Curtiss Exhibition Team with a venomous exit.

Soon after, possibly out of spite, possibly in good fun, Lincoln dressed up as a female aviator, and in a jab aimed at the first female aviator, Blanche Stuart Scott, another member of the Curtiss exhibition team, flew into Chicago, tearing between the buildings while pretending to have no control over the plane. “With silk skirts fluttering in a 40-mile gale and plumed hat straining at a long pink chiffon veil which anchored it to his head, Beachey sped around the air, now and then shaking a bespangled slipper at the astonished crowd,” reported the Augusta Chronicle, who also mentioned that his antics sent terrified pedestrians and automobiles fleeing in all directions from what they believed to be an incipient plane crash. Blanche would retire from aviation later that year, reportedly due to her frustration with the male-dominated aviation industry not allowing women to become mechanics or engineers.

Most people who have as profound an impact on an area of study or an industry like Octave Chanute did on aviation tend to spend most or all of their lives involved in that pursuit. But for Chanute, though he became interested in aviation at a young age, it wasn’t until his late 50s that he was able to start actually pursuing his interest in aviation, and his 60s before he began the flying experiments and glider testing for which he is most often remembered. But in the roughly 21 years he was heavily involved in aviation, he had an immense influence on the field of study just as it was [Click here to read more…]

Death Toll Rises as Countless Young Aviators Attempt to “Do a Beachey”

As his fame spread like wildfire, Lincoln J. Beachey’s influence on aspiring aviators became more noticeable, and as his tricks became more elaborate, the impact on other aviators became more tragic. Over the years, the phrase to “Do a Beachey” became commonly heard along the tarmac and in the crowds at airshows. Every pilot who wanted fame and glory had to somehow emerge from Lincoln’s shadow, one that had been cast over the nation and some may say, the entire world of aviation. One such aviator and a good friend of Lincoln, Charles Welsh, began to imitate the awe-inspiring spirals and rolls made popular in Lincoln’s aerial exhibitions. His wife, nervous due to the high fatality rate of plane crashes (which had been skyrocketing as Lincoln became more popular and other aviators became more determined to emulate him), begged Charlie to “cut out the spirals,” to which he responded, “Beachey does them, so I must do them if I am to get the money.”

Two weeks later, Charlie was flying over Trenton, New Jersey, attempting a reverse spiral when a wire supporting the wings of his plane snapped, sending him plummeting to his death. This was only one of many deaths others would pin on Lincoln and his impossible stunts. In fact, in one year 24 pilots died while flying, attempting to “Do a Beachey,” and over the years that number increased so drastically that the city of San Diego attempted to legally prevent Lincoln from ever being able to fly again, citing him as a bad and dangerous influence.

After Charlie’s death, Lincoln was on a train traveling through Albuquerque, New Mexico on his way to go speak at the Olympic Club, the oldest athletic club in San Francisco, when Charlie’s widow and two fatherless babies approached his cabin. The widow threw herself against Lincoln hysterically, screaming curses and blaming him for the fate of her husband. She cried, “You killed Charlie, he’s in the baggage cart in a coffin,” and “You made Charlie do it.”

Once Lincoln arrived at the Olympic Club, he wordlessly approached the podium, and with his usual dramatic flair stated,

You could not make me enter an aeroplane at the point of a revolver. I am done. They called me the Master Birdman, but there was just one thing which drew crowds to my exhibitions- a morbid desire to see something happen. They all predicted that I would be killed, and none wanted to miss the sight. They paid to see me die. They bet, and the odds were always against my life. –The New York Times, May 12, 1913

A Short Retirement and a Tragic Death

Lincoln J. Beachey’s retirement was an abbreviated one at best. His competitive nature drove him back to the yoke after the news of another aviators triumphs reached San Francisco. Adolphe Célestin Pégoud, French aviator and decorated veteran, flew what he believed to be the first-ever aerial loop on September 21, 1913. This feat was then widely publicized and the news was spread all across the globe. It wasn’t until the Russian Czar Nicholas II invited Pégoud to perform in Moscow that he learned the first pilot to fly the loop was actually a Russian army pilot named Pyotr Nesterov, who had did so only 12 days earlier in a Nieuport IV monoplane at an airfield near Kiev, Russia.

At this, Glenn Curtiss finally relented and engineered a plane powerful and agile enough to allow Lincoln to complete the much sought-after loop. The new plane was called the “Little Looper,” and soon enough, Lincoln was behind the controls, preparing for take-off near Lake Keuka, New York. The news that Lincoln had emerged from retirement to be the first American to do a loop-the-loop had reignited the public’s obsession with aerial stunts, and so the surrounding areas were carpeted with onlookers, despite Lincolns wishes. He had been struggling to make a decent living do airshows because it was easy enough to view the events for free from outside the fairgrounds that hardly anyone felt inclined to buy a ticket. Such a group, composed of two sisters, Ruth and Dorothy Hildreth, and their dates, two Navy Officers, had climbed onto the top of Lincoln’s hangar to get a better view of the spectacle.

Shortly after take-off, Lincoln used his technical skills to dip the wing of the Little Looper as a sort of wave or salute to the group of onlookers, which they enthusiastically returned. Lincoln turned his plane around, preparing for the loop, but as he flew over the hangar, something went wrong.

When directly over the heads of the Hildreth party, Beachey’s machine was seen to dip dangerously. Immediately afterward, the aeroplane hurled the girls and the Lieutenants to the ground, a distance of ten feet. The aeroplane careened wildly and plunged thirty feet to the grass. Beachey was unseated and the machine was wrecked. Spectators hurried to the Misses Hildreth and their escorts. Miss Ruth Hildreth, the younger of the sisters, was unconscious with a deep wound in her head. Miss Dorothy Hildreth also was insensible. Lt. Bellinger and Lt. Richardson were able to arise when aided. Miss Ruth Hildreth was dead when a physician reached the spot. Her head had struck a sharp corner of an automobile. The other sister was removed to the home of John Scott and it was found she had suffered fractures of an arm and a leg and that her chest was crushed. Lieuts. Bellinger and Richardson had suffered bruises and cuts. Beachey had sprained his arm and ankle, but he walked about the field soon after the incident. He said he wished it had been his life rather than a girl’s that was lost.

And for the second time, with great sadness in his heart, Lincoln retired from aviation.

An Even Shorter Retirement

Less than a fortnight later, Lincoln J. Beachey woke up to a large poster plastered on the wall of his bedroom. The hand-drawn poster depicted him flying upside down (the wings of his plane were painted with three foot high letters reading “Beachey” so it was fairly recognizable), which was a trick he had never successfully done. It turned out that his manager, in an attempt to pull Lincoln out of the misery in which he had been wallowing, had the poster made and snuck into his bedroom while he slept. The ploy for Lincoln’s attention worked, and the very next day the two men were on a train headed to San Diego with his newly repaired plane in the baggage car. At the airshow on November 25, 1913, Lincoln became the first American to ever successfully complete a loop-the-loop. In response to completing the goal that had eluded him for years, Lincoln wrote,

The silent reaper of souls and I shook hands that day. Thousands of times, we have engaged in a race among the clouds, plunging headlong into breathless flight, diving and circling with awful speed through ethereal space. And many times, when the dazzling sunlight has blinded my eyes and sudden darkness has numbed all my sense, I have imagined him close at my heels. On such occasions I have defied him, but in so doing experienced fright which I cannot explain. Today, the old fellow and I are pals.

Two days later, he returned on Thanksgiving Day and did three loops in a row, and the number would only increase exponentially from there. At first, 10 loop-the-loops were enough to excite the crowds, until an Englishman managed to do 27 loops. The following week, Lincoln had done 28. Shortly after, a French aviator did 64 loops, and so Lincoln did 65. By the end of his loop-the-loop obsession, Lincoln could do an unprecedented 80 loop-the-loops in one afternoon.

Although their claim to the first powered flight may be in dispute, one thing that is not is that the Wright Brothers’ impact on the field of aviation was monumental. They provided some incredible innovations and made leaps forward that seem almost ludicrous. In fact, really digging into their story and their contributions to aviation would be a much longer, more involved task. Additionally, though history has been kind to the Wright Brothers, this appears now to have been in part because Orville wielded such absolute control over their legacy [Click here to read more…]

British science enthusiast and writer David Darling discussed Orville Wrights skepticism about Lincoln’s feats. Presumably due to his lingering hatred of long-time rival Glenn Curtiss, who was by this time a close associate of Lincoln, Orville claimed that the tricks were nothing but optical illusions and “promoter hype.” Until he saw Lincoln fly in person, that is:

Loop after loop Beachey performed, then flipped his craft over, flew it upwards until it stalled, fell backwards, tail first and upside-down, brought his tail up until he stalled backwards upside-down, and repeated the whole maneuver, again and again, falling out of the sky as he tipped back and forth – all with his arms stretched wide, operating the plane with his knees and body alone. Wright couldn’t believe his eyes: ‘An aeroplane in the hands of Lincoln Beachey is poetry… His performance not only surprised me, but amazed me as well. He is more magnificent than I imagined.’

After he grew comfortably content (and thus bored) with loop-the-loops, Lincoln set his sights on other records. Later the same year, Lincoln became the first aviator to fly a plane entirely indoors. At the San Francisco World’s Fair, Lincoln set up his biplane inside the spacious, aptly-named Machinery Palace, and launched it into the air, repeatedly circling around the hall at an intimidating 60 mph before landing again, safely, on the floor of the Palace.

The Championship for the Universe

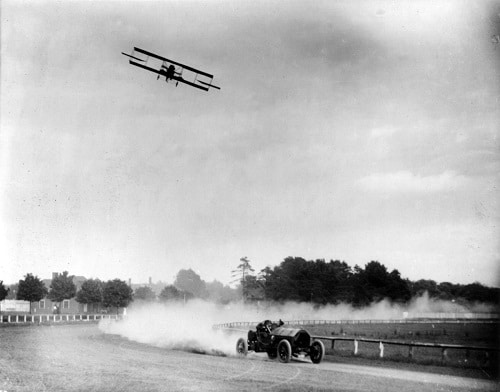

The following year, Lincoln Beachey was again coerced into action by a poster. His publicity agent had devised a plan and illustrated it on a spectacular poster, which showed Lincoln Beachey, the Demon of the Sky, competing with record-breaking racecar driver Barney Oldfield, the Daredevil of the Ground. Both men were intrigued by the idea, and so Lincoln and Barney set off on a country-wide tour depicting a race that would determine the Champion of the Universe.

Custom-built tracks were raised all over the country, complete with extra-high walls that would shield the races from hopeful freeloaders (and thus encourage more people to buy tickets). Around the track, Barney Oldfield would drive his infamous, cherry-red 100 horsepower Fiat against Lincoln’s Little Looper, stirring up clouds of dust and acrid smoke as the engines strained against the determined hand of their masters. Though the plane was significantly faster, the two men staged the races to look like they were neck and neck, occasionally alternating who would win each time. In addition to the mock races with Oldfield, Lincoln performed at nearly 130 airshows for over 17 million people (over a sixth of the country at the time) in one year.

A Proud Patriot Concerned About the Future

One of the more lasting impacts Lincoln Beachey had on American aviation history was his promotion of a stronger air force. At the time, countries all over the world were fortifying their military with aerial divisions, and in 1914, Russia, Germany and France all had over 1,000 military aircraft at their disposal, where the US military only had 23. Lincoln used his plane to distribute millions of brochures all over the country, encouraging people to vote for military investment in an air force. Lincoln invited a group of government officials to an airshow where he would demonstrate how powerful an ally an air force would be to the military, but only two cabinet members appeared for the demonstration.

Frustrated with the stubborn blindness of the government, Lincoln planned another surprise White House visit, this time in the form of an aerial attack.

The buzz of Lincoln’s biplane grew louder and louder as he approached the White House, where President Woodrow Wilson was reportedly working in his office. By the time President Wilson was concerned enough by the sound to look out the window, the plane was mere seconds away from impact. In his typical flourishing style, Lincoln tore upwards at the very last second and continued to dive bomb the White House and other government buildings on Capitol Hill. Frightened citizens and congressmen poured from the buildings to see what was causing the commotion, and a small amount of chaos spread through the streets as most people were temporarily under the impression they were truly under attack.

By the time Lincoln had gathered the attention of nearly everyone in Washington, he landed and announced “If I had had a bomb, you would be dead. You were defenseless. It is time to put a force in the air.” The staged attack appears to have had the intended effect, and Congress voted to increase military spending. The Air Force evolved into the formidable branch the US has today, and Lincoln remained a vocal supporter throughout his career, continuing on with military propaganda events, despite turning down a powerful position offered to him by the government.

In early 1915, a few days before the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco was packed with tourists and aviators exploring the City by the Bay before the official events of Exposition began. Because he now had a burgeoning and captive audience, Lincoln arranged another shocking display of airplane military potential. He had a life-size wooden replica of the battleship the USS Oregon, which had been loaded with 50 armed explosives, and the Navy even staffed the ship with a crew to add realism. The model was anchored about a mile out in the San Francisco bay, supported on two large barges, and the crew was secretly evacuated. Lincoln ripped through the air, the loud rumbling engine drawing the attention of passerby, and he dove low towards the mock USS Oregon, dipping his wing as he dropped a “smoking bomb” onto the rigged model, igniting a string of 50 explosions that sent great gusts of vaporized sea water and smoke billowing into the air. Panic set in as the unknowing audience became convinced they were under attack and just saw graphic and traumatizing mass murder. The unharmed Navy crews onshore appearance quelled the fears, and terror turned to awe as the public realized this was another of Lincoln’s propaganda events.

The End of an Era

Only a few days later, on March 1915, a crowd of 50,000 gathered in the fairgrounds to watch Lincoln J. Beachey’s spectacular flying stunts, with another 200,000 spectators packed into the surrounding hills for a free viewing. This event would unveil Lincoln’s latest and most powerful plane yet, the Beachey-Eaton Monoplane, capable of flying at over 100 mph. The event began successfully, with Lincoln guiding the monoplane high over Alcatraz Island and the San Francisco bay, completing a loop the loop or two to get the crowd going.

Amongst the deafening cheers of the onlookers, Lincoln turned the plane onto its back in possible preparation for an inverse loop, just 3,000’ over the water. The plane began to sink in the air, and Lincoln attempted to salvage the situation by turning the plane 180 degrees onto its belly, but the strain of the maneuver cracked the rear spars, and the force of the air against the wing of the monoplane cracked it down the middle with a bone-rattling sound, allowing the wind to rip the wings completely from the body of the plane.

Now, locked in a nose-dive from which he could not escape, Lincoln and his mangled monoplane crashed against the surface of the bay, quickly sinking into the freezing water.

It would take rescuers nearly two hours to find the body of Lincoln, still strapped tightly to his monoplane, which was discovered close to the shore of the bay near Fillmore Hill, bringing him back to where his fatal love of flying began. With the dark irony only Life can convey, Lincoln and his monoplane were recovered by the USS Oregon, the battleship Lincoln pretended to destroy just days before. The autopsy reports would show that Lincoln survived the impact with only a broken leg, but drowned when he was unable to free himself from the restraints that were supposed to save him.

The public was so devastated by the shocking death of Lincoln Beachey that phone calls in and out of the city jammed the phone lines for an entire 24 hours. Lincoln, the first of his kind, a familiar hometown hero with a powerful love of his country and a natural-born showman had been taken from his loving audience far too soon, at the tragically young age of 28. Though he had turned down the offer for a career in the air force he helped grow, he died as one of the highest ranking officers in the Volunteer Aviation Reserve, and was remembered fondly by a member of the organization, Albert Lambert, who said, “It was his unlimited courage more than anything that enabled Beachey to live as long as he did.”

A Lasting Impact on Aviation

Lincoln J. Beachey was the first aviator to invent the stall recovery, the first American to master the loop, the first man to build a plane specifically designed for aerobatics, the first aviator to fly inside a building, the first aviator to achieve terminal velocity, in addition to attracting the largest congregation of people in the United States (at the 1911 Niagara Falls event), and he has even been called the 8th Wonder of the World and the Greatest Aviator in History by Glenn Curtiss, Orville Wright, Thomas Edison, and hundreds of newspapers. Legend has it that he was even able to scoop a handkerchief off the ground with the wing of his biplane mid-flight, and yet, most modern Americans have never heard his name. Why is it that possibly the greatest pilot in history (especially given the equipment he was working with) has remained largely unheard of 100 years after his death?

Historians presume that his fame was outweighed by the horrors of World War I, which was ramping up when he died, or maybe he was forgotten in the glitz and glam of the Roaring Twenties, a decade obsessed with another record-breaking aviator, Charles “Lucky Lindy” Lindbergh. Whatever the reason, Lincoln J. Beachey deserves to rise above the rest, as he did throughout his short, but colorful career in aviation.

Hanging between the cloud-dashed sky and churning dark waves, Charles Lindbergh fought his exhaustion. He had been conscious for more than 40 hours, and his body craved sleep. Despite the bitter cold, the endless droning of his plane’s engine and the unbroken monotony of the seascape were lulling him to sleep.

But sleep was the one thing he could not afford. All alone in the Atlantic skies, surrendering would mean certain death. And so he struggled to stay awake [Click here to read more…]

Sources:

2 Comments