Alberto Santos-Dumont: the “Little Saint” with a Big Impact

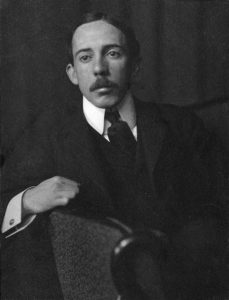

Ask any random person off the street who flew the first airplane, and odds are they’ll answer confidently, “The Wright Brothers.” Even most pilots would agree that it was the American duo who first took to the skies in a heavier-than-air craft. However, according to the people of Brazil, the honor goes to Alberto Santos-Dumont, national hero, and famed aviator, due to a loophole in the stipulations by the Federation Aéronautique International for the first true airplane.

Early Life in Brazil

The youngest son of a wealthy Brazilian coffee mogul, Alberto Santos-Dumont was born on July 20, 1873, in the village of Cabangu, Brazil. From a young age, Alberto was intrigued by the tractors and other machines used on the coffee plantation in his youth, and after reading more than his fair share of Jules Verne became obsessed with the concept of flying machines.

As a teenager, Alberto Santos-Dumont went to a science and engineering-centric high school, providing him with the additional knowledge and experience needed to make his lifelong dreams of flight a reality.

Alberto’s father, Henriques, suffered a severe horseback riding accident that left him partially paralyzed, forcing him to seek advanced medical treatment. He traveled to Portugal to see doctors, and when he didn’t find successful treatment there, traveled to Paris with his son. After consulting with specialists, Henriques learned he only had a short time to live. He sold the coffee plantation and moved to Europe with his wife and family.

Henriques told his son to use his portion of the family wealth to “make a man out of himself,” and pursue his interests in physics and chemistry. Alberto then returned to Paris and studied those subjects, in addition to astronomy, electricity, and mechanics with a private tutor over the next four years, occasionally returning home to visit Brazil.

Making a Life for Himself in Paris, France

One of the first things Alberto did on arrival in Paris in 1891 was to arrange for a flight in a balloon. However, upon finding out it would cost 1,200 francs for a two-hour flight, he decided against the flight, saying, “If I risk 1,200 francs for an afternoon’s pleasure I shall find it either good or bad. If it is bad, the money will be lost. If it is good, I shall want to repeat it and I shall not have the means.”

This business savvy was apparently only limited to new experiences, as shortly after this, Alberto bought a Peugeot automobile, which he would replace with a De Dion-Bouton motor-tricycle in the next couple of years. Between 1892 and 1897, Alberto would travel back to Brazil many times, but his love for Paris always brought him back.

Before leaving Brazil in 1897, Alberto bought a book telling the tale of Salomon August Andrée’s ill-fated attempt to fly a balloon to the North Pole, written by the balloon manufacturers Lachambre and Machuron. Alberto declared the book to be “a revelation” and decided to get in contact with the balloon manufacturers when he reached Paris.

Alberto Santos-Dumont’s First Balloon Flight

Alberto met Alexis Machuron and took off from Vaugirard, Paris and flew the balloon for two hours and 100km, eventually coming down at the Château de Ferrières. It was love at first flight. Alberto and Machuron took a train back to Paris, during which Alberto enthused about balloons, and ordered one to be constructed by Machuron and Lachambre for himself. Before the balloon was completed, Alberto spent countless hours floating through the skies, performing demonstration flights for Lachambre.

His first balloon, the Brésil, was nearly 1/7th the size of the balloon he and Machuron flew to the Château, with a capacity of only 113 cubic meters. Eventually, just as he tired of the Peugeot and bought a De Dion, Alberto switched his focus from balloons to non-rigid airships, or as we know them now, dirigibles.

The Santos-Dumont No. 1-3

On September 18, 1898, Alberto took his dirigible, the Santos-Dumont No. 1 on its maiden voyage. Unfortunately, due to the small ballonet being unable to maintain the rigidity of the envelope, the No. 1 crashed on its second flight two days later.

His second dirigible design, the No. 2 was abandoned after its first flight on May 11, 1899, due to design flaws exacerbated by the weather. The day of No. 2’s first flight, it began to rain heavily, cooling the hydrogen inside the balloon, causing it to compress and contract dramatically. The envelope then folded in on itself and was caught by a gust of wind, blowing it into a copse of trees, where it was destroyed.

Shortly after the destruction of the No. 2, Alberto finished his third dirigible design (you guessed it, the No. 3), which was constructed with the hopes of eliminating the issues he ran into with the second dirigible. The envelope of the No. 3 was shorter but much larger in diameter, to theoretically make it impossible for the loss of internal pressure the Santos-Dumont No. 1 and No. 2 suffered to cause the airship to crash.

The No. 3 marked a turning point in Alberto’s career as an aviator, as it was his first coal-powered dirigible. He turned away from his faulty ballonet concept and shifted toward a lightweight bamboo keel, and away from hydrogen and toward coal gas. Coal gas had gained popularity during this time all over the world, as it was a common by-product of many factories post-Industrial Revolution.

Innovating to Win, Ending in Failure

By the time Alberto was ready to move on to the No. 4, the No. 3 had been flown successfully a number of times, bolstering Alberto’s confidence in the concept of the dirigible. The No. 4, again, differed greatly from its predecessors as it was fitted with a tractor propeller in front of the keel, as well as a bicycle saddle for the pilot’s seat, but returned to his initial designs in spirit after he acquired a hydrogen processing plant, allowing him to retry to hydrogen-as-lifting-agent and ballonet combination. With the addition of a larger, wider envelope and a four-cylinder air-cooled engine, the No. 4 became a great success.

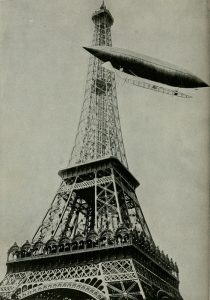

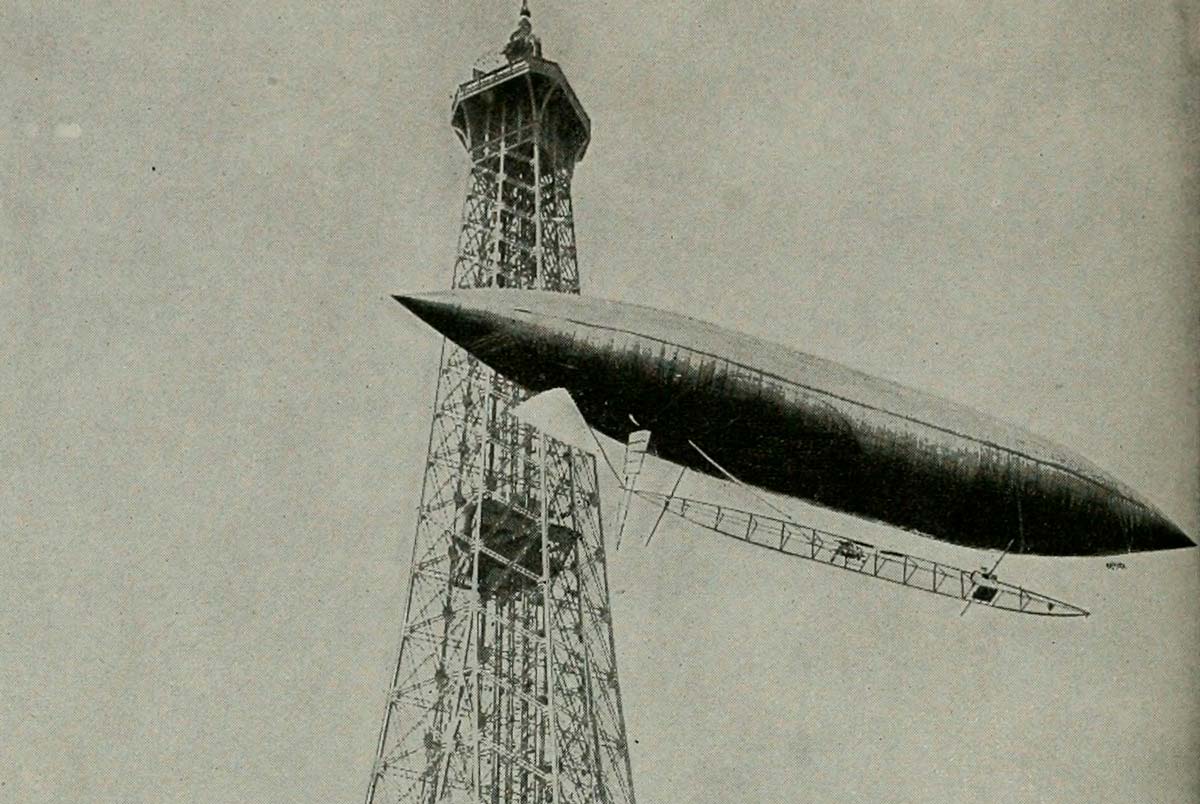

The No. 5 was designed for speed and power, with the hopes of winning the time trial between the Aero-Club de France to the Eiffel Tower and back within 30 minutes. Unfortunately, though it was more than fast enough, reaching the Eiffel Tower in just 8 minutes, a faulty valve caused the rapid decompression of the envelope, which led to a series of small disasters that would end in a near-catastrophe.

The deflation of the balloon caused some of the piano wire Alberto had used to suspend the pine gondola to get wrapped up in the tractor propeller. Unsure of how to salvage the situation, Alberto shut off the engine, which reduced any further damage to the propeller, but left him seated in a balloon with no forward power and no means of re-inflating the balloon. The wind carried Alberto and the No. 5 directly into the Trocadero Hotel, bursting the envelope in what papers described as an explosion, and leaving Alberto hanging perilously from the side of the hotel, hanging high above the stone courtyard below. Luckily for aviation, the Parisian fire brigade rescued Alberto, and he would survive to innovate another day. Unluckily, however, the No. 5 was damaged beyond repair.

The Santos-Dumont No. 6 and the Deustch de la Meurthe

Never one to be deterred by failure, Alberto immediately began construction on the No. 6, the airship that would earn him considerable fame across all of Europe.

Essentially the same design as the No. 5, with a larger envelope, and the kinks worked out, Alberto and his No. 6 would go on to complete the race between the Aero-Club de France and Eiffel Tower, winning the first place Deutsch de la Meurthe prize. After this grand achievement, Alberto Santos-Dumont became a household name in Paris, and was affectionately nicknamed le Petit Santos, which literally translates to “The Little Saint.”

Alberto would donate the winnings from the Deutsch de la Meurthe to the Parisian poor, and was additionally awarded a gold medal by the Brazilian government. Records indicate that the most fashionable of Parisians copied Alberto’s style, from his high-collared shirts to his signature Panama hat.

Sabotage

One of the best-known aviators at the time, Alberto was invited to travel to America to compete in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, in which any style of flying machine had to make three laps of a 24km course at an average speed of 24km/h (15mph), and land, undamaged within 46m of the finish line. He was also invited to meet President Roosevelt in the White House.

Unfortunately, not every American was as excited to see Alberto win the race and win the $100,000, and upon arrival in St. Louis, it was discovered that the No. 7 had likely been sabotaged. A similar event had happened just prior upon Alberto’s arrival in London for a fair, and so, afraid for his airship and personal safety, he returned immediately to Paris.

Achieving Heavier-Than-Air Flight in the No. 14-bis

Alberto would continue designing and building dirigibles for most of his life but soon switched his primary focus from non-rigid airships to heavier-than-air flight. By 1905, Alberto had finished his first fixed-wing aircraft, as well as a primitive rotorcraft. On October 23, 1906, Alberto took the No. 14-bis on a 60m flight in front of hundreds of witnesses at the Bois de Boulogne Park in Paris.

The flight of the No. 14-bis marked the first powered heavier-than-air flying machine in all of Europe to be recognized by the Aero-Club de France and would win the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first (officially observed) flight exceeding 25m.

On November 12, 1906, just weeks later, the No. 14-bis again made history by setting the first world flying record recognized by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), by flying 220m in just 21.5 seconds.

Who Really Made the First Heavier-Than-Air Flight?

As I mentioned in the beginning of the article, controversy arose. According to the FAI, the stipulations for the first heavier-than-air flight were as follows:

- The flight should be done before an official organization, qualified to ratify it

- The flight should be done in calm weather and over a plain ground, and properly documented

- The machine should be able to take off from a designated area by its own means with a man on board

- The machine should carry on board the necessary source of energy

- The machine should fly in a straight line

- The machine should make a change of direction (turn and circle)

- The machine should return to the starting point

According to Dumont-supporting historians, the third specification, “The machine should be able to take off from a designated area by its own means” is the damning nail in the coffin regarding the Wright Bros. place in history. By their own admission, and by the eye-witness accounts of those who saw the Wright Flyer III’s 39-minute flight (reportedly longer in duration that all flights to that point) on October 5, 1905, the aircraft was launched using a catapult, thus being propelled by means other than its own. However, on the Wright side of the coin, the Wrights had recorded making dozens of flights before they built the catapult launching system

The controversy has not yet been put to rest, and likely never will. Such is life!

Building the First Practical Ultralight Aircraft

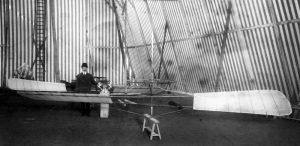

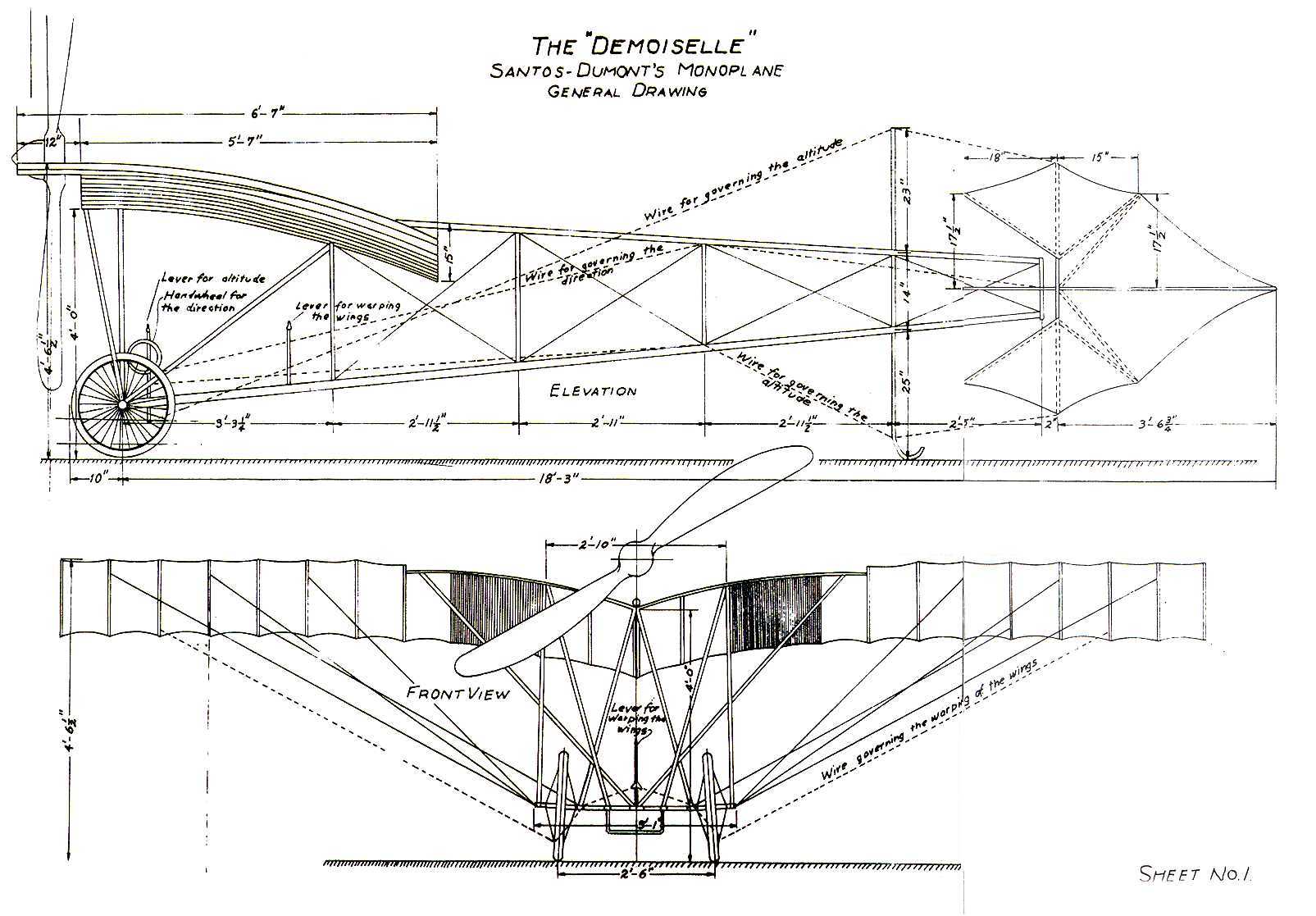

Regardless, Alberto continued to innovate, and eventually, by No. 19, had created the first practical ultralight aircraft. The Demoiselle series (Santos-Dumont No.19-No.22) were monoplanes with a wire-braced wing mounted above an open-framework bamboo fuselage. An interesting aspect of the No. 19 was its cruciform tail, which, fastened on a universal joint, functioned as both rudder and elevator. On November 17, 1907, the No. 19 would make three successful flights from the airfield at Issy-les-Moulineaux, on the left bank of the river Seine.

Because of the success of the No. 19, in 1908 Alberto partnered with the Clement-Bayard company to mass-produce the Demoiselle. Their initial production run was meant to build and sell 100 aircraft, but only ended up building 50, and sold even less. Profits and production goals notwithstanding, the Demoiselle No. 19 was the world’s first series production aircraft. It would continue to undergo improvements, and by 1909 was capable of speeds up to 120km/h (roughly 75mph).

History of the Experimental Certificate

The current FAA regulations for experimental amateur-built (or homebuilt) and kit-built aircraft state: ‘Special airworthiness certificates may be issued in the experimental category for: Operating amateur-built aircraft: to operate an amateur-built aircraft in which the major portion has been fabricated and assembled by persons for their own recreation or education. Operating kit-built aircraft: to operate a primary category aircraft that was assembled by a person from a kit manufactured by the holder of a production certificate for that kit, without the supervision and quality control of the production certificate holder.’ This ability to certify and fly homebuilt and kit-built aircraft allows a great deal of satisfaction for a large number of aviation enthusiasts [Click to read more…]

The current FAA regulations for experimental amateur-built (or homebuilt) and kit-built aircraft state: ‘Special airworthiness certificates may be issued in the experimental category for: Operating amateur-built aircraft: to operate an amateur-built aircraft in which the major portion has been fabricated and assembled by persons for their own recreation or education. Operating kit-built aircraft: to operate a primary category aircraft that was assembled by a person from a kit manufactured by the holder of a production certificate for that kit, without the supervision and quality control of the production certificate holder.’ This ability to certify and fly homebuilt and kit-built aircraft allows a great deal of satisfaction for a large number of aviation enthusiasts [Click to read more…]

Despite the troubles Alberto encountered in America years prior, the June 1910 edition of the Popular Mechanics magazine recognized the Demoiselle as “better than any other which has ever been built, for those who wish to reach results with the least possible expense and a minimum of experimenting.”

Alberto Santos-Dumont Calls it Quits on Aviation

On January 4, 1910, Alberto would make his last flight as a pilot. Flying above the French countryside, one of the wire bracings on Alberto’s Demoiselle snapped, crumpling the wing and sending them both toward the earth. Fortunately, Alberto was only flying around 25m AGL and suffered only bruises. The shock of the accident, however, left a lasting mark.

In March of that same year, Alberto announced he was retiring from aviation. A deep depression had gripped him and would hold tightly until his death. He locked himself in his home amongst rumors that he suffered a nervous breakdown. Historians now speculate that he learned of his multiple sclerosis (MS) around this time, likely adding to the depression he was already experiencing.

The following year, Alberto moved to Benerville-sur-Mer, a seaside village in the Northwestern region of France, and took up astronomy as a hobby to occupy his lonely mind. He lived there alone in solitude until the outbreak of WWI in 1914, after which he was denounced as a German spy, due to his use of a German-manufactured telescope and “unusual” accent. How quickly the people forget their once-heroes in times of adversity!

Distraught at the allegation, and suffering a severe depression because of this betrayal and his MS, Alberto burned his papers and plans, and spent most of the 1920s traveling from hospital to hospital (French and Swiss “sanatoria”), seeking treatment, just as his father had done decades earlier.

The Saddest Welcome

In 1928, Alberto decided to return home to Brazil. A welcome party was arranged, and the dozen or so leading Brazilian scientists boarded a seaplane to pay a “flying welcome” to the Brazilian Father of Aviation upon his arrival on the luxury liner, the Cap Arcona.

Disaster struck, and the seaplane and all onboard perished after crashing into the waves. This dramatic and crippling loss for both the Brazilian scientific community and Alberto himself sent him even further into misery. Dejected, he returned to Switzerland, where he would remain in solitude until his nephew dragged him home to Brazil in 1931.

A Sadder Goodbye

On July 23, 1932, in the Brazilian city of Guarujá, Alberto took his own life. He reportedly hanged himself due to his depression over his illness, as well as the use of aircraft in the São Paulo Constitutionalist Revolution. He, like many visionaries, never wanted his inventions to be used as weapons, and regardless of the causes the revolutionaries fought for, the aircraft became a symbol of death.

Alberto Santos-Dumont died a lifelong bachelor, with no children or wife to grieve his loss. Until his dying day, however, he kept the portrait of a married Cuban-American woman, Aida de Acosta on his desk, beside a vase of fresh flowers. Aida was the only person Alberto ever allowed to fly his aircraft, and in 1903, after piloting his dirigible No. 9, she would technically become the first woman to pilot a powered aircraft. They didn’t keep in touch, and after Alberto’s death in 1932, Aida said she hardly even knew him.

The body of Alberto Santos-Dumont was buried in the São João Batista Cemetery after a state funeral, honoring the Brazilian aviation pioneer. His heart is preserved in a golden globe in the Brazilian National Air and Space Museum.

Dear Carly

Very clear and complete article about one of the most famous Brazilians in history. Yours was the first one I read (as a Brazilian), which was not biased. In my opinion, the big difference between Santos-Dumont and the Wright Brothers is that the former was very rich, and do not have any commercial interest while the latter people had modest income, and needed to preserve their “secret” in order to obtain a patent.

Other important device designed by the french clockmaker Cartier, was the first wrist watch, in order to let Dumont pilot his ballons without having to remove his hands from the controls to get his pocket watch.

Anyway, congratulations for this excellent article, and I have already shared it in my facebook account. Keep up the good work, and if you visit Brazil do not forget to visit Dumont’s former home “A Encantada” – The enchanted – in Petropolis, a city about 100 miles from Rio de Janeiro.

Thank you for your comment Gustavo! I really enjoyed researching and learning about Dumont, his life story was beautiful, incredible, and by the very end, heart-breaking.

I will continue to do my best writing articles about aviation pioneers- it’s so fascinating to see how far we’ve come! It’s very easy, being born and bred in the US, to attribute most of the aviation advancements to American innovators, so it’s exciting to expand my own horizons, as well as those of our readers!

Thanks for reading! 🙂

Very Nice!!!

Dear Miss CARLY COURTNEY, congratulations for your ressearch ‘cos the life of S=D was one

of the most increadible of all human history !! As a Museum 14 Bis project author, I’m your disposal

to talk about my Hollywood movie to him, next year – 2020. Best Regards .. Rubens Heredia = FB page,

Museu 14 Bis.