“The rest of the world may have grown complacent by then about aeroplanes flying in the night, but our world had barren skies. Ours was a young world, eager for gifts—and this was one.” Beryl Markham, West With the Night

Some people meet expectations while others defy them. Beryl Markham was of the latter. And it was with such defiance of expectation that piloted her into a life of adventure, eventually becoming the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic from east to west.

Horse Trainer, Writer, Pilot

Born Beryl Clutterbuck on October 26, 1902, in the village of Ashwell, Central England, she moved with her father to Kenya when she was four years old. There she grew up on her father’s horse farm in Njoro near the Great Rift Valley. Her childhood was full of adventure, playing, and hunting. She ran wild with the local boys, ate with her hands, and first spoke Swahili before any other language. In her childhood surrounded by horses, with her father an accomplished horse trainer, she practically grew up in the saddle. In fact, she even told a friend once that she felt better on a horse than on her feet. Perhaps this is why she would find herself perfectly comfortable in an airplane, sitting high above the ground.

With only two-and-a-half years of formal education, she was keenly professional. Beryl became a successful and renowned horse-trainer in Kenya while just barely an adult. This feat is doubly impressive considering she was the first woman to obtain a trainer’s license in Kenya.

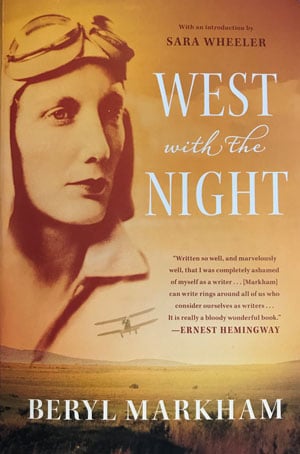

Before she set world records as a pilot, she won the prestigious Nairobi St. Leger horse race in 1926. Adding to the adventure of her life, she also became a best-selling author with her memoir, West With the Night, published in 1942. However, the book itself, and by association its author, got lost among the fog of war; strong reviews were not strong enough to keep the memoir in print. And there it lingered in relative obscurity until 1983 when it was republished. With the book’ s republication, Beryl Markham was back in the public eye.

Within its text, she selectively chronicles some of her life’s adventures, including her pioneering aviation work. Despite its title, and despite her influence on the aviation world, Beryl’s transatlantic feat makes its appearance a mere thirteen pages from the end of the book. But for a life so full of adventure, a bookend may be the best end to such storytelling, after all.

My Journey to Becoming a Pilot in Kenya

My Journey to Becoming a Pilot in Kenya

My dad, who is a Kenyan diplomat, was sent to Somalia on assignment and I came along. This was my first time on board an aircraft and in an airport. I recall the day in black and white as we walked down the ramp on the airside to the plane which was a distance away, and passing all these huge planes… [Read More]

A Message of Enterprise

Ever the non-conformist, Beryl decided to take flight in a land where, as she puts it, the skies were barren. In Kenya at this time, airplanes were a brand-new thing. It was famous English aviator Tom Campbell Black who brought airplanes to Kenya—and into Beryl’s life.

Tom Black was an RAF veteran who had served during the Great War. After settling in then-British East Africa, he brought flying to the continent. In September 1928, Black’s de Havilland DH.51 became the first aircraft registered in Kenya. He also established the country’s first commercial air service, Wilson Airways.

When Tom Black flew into Kenya, he sparked something in Beryl. In West With the Night, she writes, “Something about that irreverent contrivance of fabric and wires and noise, blustering through that chaste arena of the night, had stirred the course of my thoughts to restless eddies.”

It was the start of something new in her life.

“’And of course you’re going to fly,’” says Tom in her memoir. “’I’ve always known it. I could see it in the stars.’”

And fly she did.

Taking to the Skies

Tom Black became Beryl Markham’s flight instructor, teaching her to fly first in a D.H. Gipsy Moth. She learned to fly without earphones, without Tom telling her what she was doing wrong. Instead, he taught her to fly by instinct and intelligence. And it must have worked because she earned her pilot’s license in August 1931 and gained her commercial pilot’s license by the end of the year.

As to her ‘B’ license, she viewed it as the “flyer’s Magna Carta.” She had flown nearly one thousand miles and spent a hundred hours or more studying navigation books. With this achievement, Beryl moved on to an entirely new adventure.

“I had abandoned race-horse training altogether, keeping for myself only Pegasus.”

For the next three years post-commercial license, Beryl earned money by freelancing: everything from elephant spotting for safaris, ferrying doctors to ill settlers, and delivering mail. She was actually one of the first bush pilots, capable of flying in rough terrain. Beryl leased a Leopard Moth for when she had two passengers and flew her Avian when she had only one. During her time scouting game, she met Ernest Hemingway in 1934; his opinion of her writing would later bring West With the Night back into the spotlight and onto the bestseller’s list.

An Atlantic Crossing

On September 4, 1936, Beryl Markham left Abingdon Royal Air Force field in Britain in a single-engine Percival Gull monoplane, determined to cross the Atlantic.

Her dream of becoming the first to traverse the Atlantic from east to west was not the easiest accomplishment.

Charles Lindbergh had made the first transatlantic crossing in 1927 when he flew from New York to Paris. Amelia Earhart became the first woman to do so in 1932 when she flew from Newfoundland to Ireland. But these flights were west to east, and arguably easier, flying with the wind.

Three months after Earhart’s flight, a Scottish pioneer aviator by the name Jim Mollison became the first to perform an east-to-west solo transatlantic flight from Ireland to New Brunswick, Canada. While she wouldn’t be the first, she would be the first woman—and she would be the first to fly from England which, to her, was incredibly significant.

The direction of the winds wasn’t the only challenge against her. She decided to make her flight in September, which meant the weather was also against her.

Why risk it? Others had asked her this question, just as she had asked it of herself.

“By his nature a sailor must sail, by his nature a flyer must fly. I could compute that I had flown a quarter of a million miles; and I could foresee that, so long as I had a plane and the sky was there, I should go on flying more miles.”

Beryl Markham made her journey in a Vega Gull, a plane she had the opportunity to witness at every stage, from birth and growth to eventually even death.

Without a radio, Beryl really only had her judgment to get her to North America safely and her dear friend Tom Black reminded her not to misjudge anything. But she also had tokens of luck. Jim Mollison, her east-to-west predecessor, lent her his watch that had gotten him across the Atlantic. Brian Lewis gave her a life-saving jacket which she left behind in favor of warm clothes. Jack Cameron bestowed her with a sprig of heather as a blessing of Scotland.

So very often it seems that when an ambition can begin badly, it does, and so did Beryl’s flight. Within a half hour, she lost her chart of the Atlantic when it blew out the window. She experienced a storm as she crossed Ireland and was essentially blinded by driving rains. Her fuel tank had no gauge; she was flying only with its written assurance: This tank is good for four hours.

While flying somewhere above the sea, the Vega’s motor coughed and died. Eventually, it bursts back to life, and she never knew how close she was to the ocean waves.

Making Aviation History

The plan had always been to land In New York. That was her goal. So, when her engine began to shutter, sputter, and eventually die before reaching New York, it was a disappointment, to say the least.

“If I had made the land, I should have been the first to fly the North Atlantic from England, but from my point of view, a forced landing was a failure because New York was my goal.”

After twenty-one hours and twenty-five minutes of flight, Beryl Markham had successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean from East to West. And though her landing spot was a no-name Nova Scotia bog, rather than Floyd Bennett Field, she was safe and she had made it, despite a nose-in in landing in the soft bog.

The next day, she did fly into New York:

“I did step out of a plane at Floyd Bennet Field and there was a crowd of people still waiting there to greet me, but the plane I stepped from was not the Gull, and for days while I was in New York I kept thinking about that and wishing over and over again that it had been the Gull, until the wish lost its significance, and time moved on, overcoming many things it met on the way.”

The End—But Not Really

Beryl Markham ends her memoir only a couple pages beyond her historic flight. After her crossing, she struggled to find the adventure in life.

She lived in the United States for a time and worked in Hollywood as a consultant in films dealing with flying or Africa. She worked on her memoir, West With the Night, and eventually returned to Africa in 1950 where she picked up where she left off with horses. She lived in Kenya, South Africa, and Rhodesia, and became one of Africa’s most successful racehorse trainers.

In 1982 she received a letter that would change the last few years of her life. George Gutekunst, a California restaurateur who introduced himself as a friend of Jack Hemingway, Ernest Hemmingway’s son, had read a collection of Ernest’s letters. One letter, in particular, lavishly praised Beryl’s writing and described her memoir as a ’bloody wonderful book’. Gutekunst persuaded a publisher to reissue it and this time it was a huge success. It sold 100,000 copies and resulted in a television documentary, Shadow of the Sun.

Beryl Markham died a wealthy woman in Nairobi on August 3, 1986. However, according to her own account, she was not a happy one.

Sources:

Markham, Beryl. (2013) West With the Night. New York, NY: North Point Press. (original work published 1942).

Mortimer, Gavin. “Beryl Markham: Britain’s Amelia Earhart“, The Telegraph, Retrieved 12-15-2017

Obituary, The New York Times, Retrieved 12-15-2017

Featured Image: Courtesy of Tekniska Museet, used under CC BY 2.0

Pancho Barnes: The Most Unladylike Aviatrix in History

Pancho Barnes: The Most Unladylike Aviatrix in History

A couple years of partying and being a bad wife and an absent mother later, in 1928, Pancho decided she wanted to learn to fly while driving her cousin to his flight lessons. She started taking flight lessons from a WWI pilot, Ben Caitlin (her cousin’s instructor), in an airplane that would give the modern day FAA a heart attack. There was only one instrument (an oil gauge), and their “artificial horizon”… [Read More]

Leave a Reply