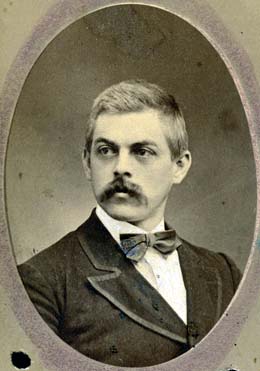

William Boeing

William Boeing was a visionary entrepreneur and pioneer in the field of aircraft manufacturing. Guided by his steady hand, a small airplane manufacturing company was able to grow into a massive corporation, engaged in a number of related industries. And though legislation after the Great Depression forced him to disperse the corporation and sell his interests in the Boeing Airplane Company, he never lost his passion for aviation. During World War 2, he continued to consult with the company that bore his name and lived long enough to see that company enter the jet age. William Boeing has been described as both private, and a perfectionist who insisted on getting the facts straight. Outside his office, on the wall, was a placard that read:

“Hippocrates said:

1. There is no authority except facts.

2. Facts are obtained by accurate observation.

3. Deductions are to be made only from facts.

4. Experience has proved the truth of these rules.”

The Early Life and Background of William Boeing

William Edward Boeing was born on October 1st, 1881, in Detroit, Michigan.

His father, Wilhelm, came from a respected and well-to-do German family. However, at the age of 20, after serving a year in the German military, young Wilhelm decided he was going to leave his hometown in Hohenlimburg and emigrate to the United States to seek adventure and his fortune. He found work as a farm laborer, but soon met and joined forces with Karl Ortmann, a lumberman, and his future father-in-law. Wilhelm bought a large section of timberland, and the associated mineral rights, in Minnesota’s Mesabi Range, the first of many such purchases that established him as a timber and mining baron. He also held positions as the director of the Peoples Savings Bank, president of the Galvin Brass and Iron Works, and a shareholder in the Standard Life Insurance Company.

Tragically, Wilhelm died of influenza in 1890, at age 42. He left behind his wife Marie, and three children, of whom the eight year old William Edward was the oldest. Marie eventually remarried, taking on the name of Owsley, and it is said that William had a strained relationship with his father-in-law. William was sent overseas to attend school in Vevey, Switzerland, but after a year, he returned to the United States and continued his education in both public and private schools.

William attended the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale from 1899 to 1902 but did not graduate. In 1903, he decided to leave college and travel West, to Grays Harbor, Washington. Here, starting with land he inherited, William taught himself the logging business and began building a new fortune. He was successful and began purchasing more timberland and financing expeditions into the surrounding areas, including Alaska. In 1908, ready to expand his business, William moved to Seattle and established the Greenwood Timber Company. In 1910, after developing a taste for boating, he bought the Heath Shipyard on the Duwamish River.

William Boeing Discovers the World of Aviation

My firm conviction from the start has been that science and hard work can lick what appear to be insurmountable difficulties. I’ve tried to make the men around me feel, as I do, that we are embarked as pioneers upon a new science and industry in which our problems are so new and unusual that it behooves no one to dismiss any novel idea with the statement that it can’t be done. – William Boeing

It was around this time that William was first introduced to airplanes. In 1909, during the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held in Seattle, he saw a manned airplane fly for the first time. This sparked a fascination with aircraft, and in 1910, he traveled south to attend the Los Angeles International Airmeet, the first major air show in the US. Here, he approached most of the aviators asking for a ride and was turned down by all of them but French aviator Louis Paulhan. Boeing waited for three days for the promised ride, before learning that Paulhan had already left the meet, moving on to give an exhibition in Salt Lake City, Utah. Many consider the ride that Paulhan didn’t give William Boeing to be the greatest missed opportunity of his life.

Four years after his visit to Los Angeles, William was introduced to US Navy Lieutenant Conrad Westervelt. They became fast friends and later that year, both finally had the opportunity to experience flying in a Curtiss-type hydroplane, piloted by Terah Maroney. They took turns flying above Lake Washington with Maroney, and afterward, decided that they could build a better airplane.

William began exchanging information with other aviators and eventually figured the first step was to learn to fly himself. He applied to the Glenn L. Martin School in Los Angeles for training and began taking a course there in August of 1915. After completing the course, he ordered a plane from the Martin factory known as the Model TA.

The machine was delivered to me in October of 1915, and, being convinced that there was a definite future in aviation, I became interested in the construction as well as the flying of aircraft. Enlisting a group of technical assistants, less than a dozen men in all, work was begun in designing the first Boeing plane. -William Boeing

During that time, William and his small group were working out of a combined factory and hangar space located on the shore of Lake Union. On June 15th, 1916, they made a test flight of the first Boeing plane, a seaplane / biplane officially called the B&W Model 1 (the initials referred to Boeing and Westervelt), but affectionately referred to as Bluebill. This aircraft, roughly 26 feet long, flew for 900 feet on the first flight. Though they may not have known it at the time, this was the birth of what would become one of the world’s largest aerospace companies.

The Boeing Airplane Company

It is a matter of great pride and satisfaction to me to realize that within the short space of 12 years, an infant company with a personnel of less than a dozen men, has grown to be the largest plant in America, devoted solely to the manufacture of aircraft, and at the present time employing approximately 1,000 men. – William Boeing

A month later, on July 15th, 1916, William Boeing and Conrad Westervelt founded Pacific Aero Products. Later that year, Westervelt, still serving in the US Navy, was transferred to the east coast. He left his position at Pacific Aero Products but sensing that it was becoming more and more likely the US would become directly involved in World War 1, he pushed William to apply for government contracts to supply the Navy with seaplanes. William was able to secure the contract, but he was missing a key part of the aircraft manufacturing process: He needed engineers.

In a clever move, Boeing addressed this problem by offering to build a wind tunnel for the University of Washington if, in return, they would establish a course for aeronautical engineering and send the most qualified graduates to Pacific Aero Products.

Shortly after the US officially joined the war, William decided to change the name of the business, and on May 9th, 1917, Pacific Aero Products became known as Boeing Airplane Company. Boeing shipped two new Model Cs to Pensacola, Florida, where they were demoed for the Navy. The Navy was impressed enough that they ordered an additional 50 Model Cs. In order to meet this demand, the company moved into the facilities at the Heath Shipyard, which became known as Boeing Plant 1.

After World War 1 came to a close, Boeing’s government contracts were canceled, and the aviation industry as a whole came to a near-standstill. This was in part because a surplus of cheap, used military aircraft flooded the market, and many aircraft manufacturers, including Boeing, were unable to sell new aircraft. In order to survive and keep from closing, Boeing was forced to diversify, and start selling, among other things, furniture, counter tops, phonograph cases and flat-bottomed boats called “Sea Sleds.”

It wasn’t long, however, before William found a new path for his company. Airmail was in its infancy, and former Army pilot Eddie Hubbard approached William with the idea of starting an international airmail route between Seattle and British Columbia. The government agreed to a trial period, and on March 3rd, 1919, Boeing made their first international air mail delivery. Though it was a success, after the trial period ended, some of William’s advisors convinced him to pass on the contract and re-focus instead on building airplanes. William, in turn, convinced Hubbard that he should pursue the contract.

By 1921, Boeing Airplane Company started to show a profit from both repairing military aircraft and designing and building new ones. Over the next decade, Boeing would become a leading manufacturer of fighter airplanes. As his company started experiencing new success, so did William personally, as he met and married Bertha Potter Paschall in 1921.

In 1925, legislation passed that opened air mail contracts to the public, and in 1927, Hubbard again approached William and convinced him to bid on the route between San Francisco and Chicago. In a move displaying incredible foresight, he was able to win the bid for the contract by deciding to use an air-cooled engine rather than a traditional water-cooled engine in Boeing’s Model 40A mailplanes.

The contract required William to have 26 airplanes in service by July 1st, 1927, and in order to accomplish this, he provided a $500,000 bond drawn from his own personal money. The Model 40A, in addition to carrying mail, also had an enclosed cabin that could carry two passengers. So for this venture, William founded a new business, an airline company called Boeing Air Transport. In the first year of operation, BAT delivered an estimated 1,300 tons of mail and carried 6,000 passengers. In 1929, William acquired Pacific Air Transport and merged it with Boeing Airplane Company and Boeing Air Transport. The resulting company was called United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, and in 1929, they acquired engine manufacturer Pratt and Whitney, Hamilton Standard Propeller Company, Chance Vought, and later in 1930, National Air Transport.

This mega corporation appeared set to rule the aviation industry until the US government stepped in. Accusing William Boeing of developing a monopoly, the government passed the Air Mail Act on June 12th, 1934, which, among other things, forced aviation companies to separate airline operations from development and manufacturing. William was forced to split United Aircraft and Transport Corporation into three separate entities. They were:

- United Aircraft Corporation, which handled manufacturing in the eastern US, and is now United Technologies Corporation.

- Boeing Airplane Company, which handled manufacturing in the western US, and is now The Boeing Company.

- United Airlines, which took over the airline operations.

Retirement from Aviation

After his company was split into the different entities, Boeing resigned as the chairman and sold his stock. Shortly after this, on June 20th, 1934, he was awarded the Daniel Guggenheim Medal for aeronautical achievement.

Now that I am retiring from active service in aircraft manufacturing and air transportation, to be so greatly honored as to be recipient of the Daniel Guggenheim Medal is a real climax of my life. As the past years devoted to aircraft activities have been filled with real romance, the many forward projects now in the making will continue to keep me on the sidelines as a keen and interested observer. – William Boeing

After this, William began devoting most of his time to other pursuits, such as breeding racehorses. He did, however, keep his promise to stay in touch with friends and colleagues in the aviation industry. He served as an advisor to Boeing Airplane Company during World War 2, and was on hand again in 1954 for the rollout of the “Dash-80.” This became known as the Boeing 707, Boeing Airplane Company’s first jet airliner, and the first commercially successful jet airliner.

On September 28, 1956, William Boeing suffered a heart attack while onboard his yacht Taconite and was declared dead on arrival. He was 74 years old, just three days away from his 75th birthday. No formal funeral was held, and his family scattered his ashes into the sea off the coast of British Columbia, where he spent much of his time sailing.

On December 15th, 1966, William Boeing was inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio, “for outstanding contributions to aviation by his successful organization of a network of airline routes and the production of vitally important military and commercial aircraft.”

Resources used for this article:

//www.nationalaviation.org/boeing-william/

//www.boeing.com/resources/boeingdotcom/history-biography/pdf/william-e-boeing-biography.pdf

//www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=8023

Interesting that this recounting includes many names but pointedly excludes Boeing’s first engineer, Wong Tsu a graduate of MIT. It’s pretty well known that without Wong, Boeing as a manufacturer of aircraft would likely not have survived its early years.