If you do hit a wire, keep flying the helicopter. Many pilots have successfully regained control of their aircraft and landed after a wire strike.

There’s the old adage, “Don’t hit the ground or anything attached to it.”

One of the things attached to it, of particular danger to helicopter pilots, are wires. On July 30th of this year, another helicopter was added to these statistics, when a Canadian helicopter hit a tower guy wire, killing a passenger.

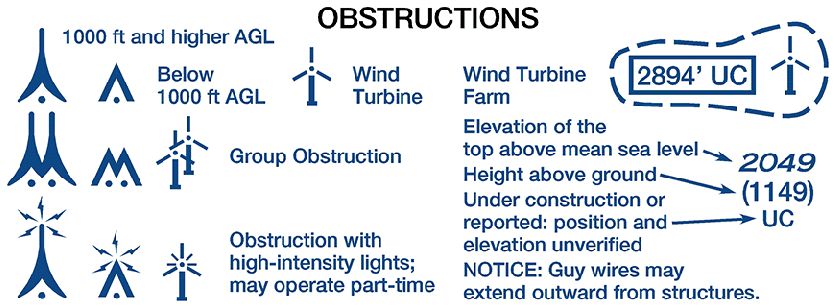

But helicopter pilots aren’t the only ones exposed to this danger; fixed-wing pilots doing crop dusting work or generally low flying are exposed to this hazard as well. Communications towers can reach higher than 2,000’ AGL and their guy wires extend up to a half-mile out.

Since 1963, wire strikes have accounted for 5% of all civil helicopter accidents (NTSB). Nearly a third of all of these accidents result in at least one fatality.

A number of studies have been produced since this time, and the findings have resulted in things that make flying a helicopter safer, such as installation of mechanical wire cutters, wire detection systems, specialized training, and better marking of objects. Still, pilots are being killed by these nearly invisible hazards. And like most preventable accidents, most of these are occurring during Day VMC conditions.

Wires in the United States

There are over five million miles of wires in the United States and growing every day. The towers that carry these lines are anywhere from 30 feet tall to 150 feet tall. They extend across buildings and through canyons and can be found everywhere from urban to desolate rural areas.

Transmission towers, for cellular, television, and radio networks, are also being constructed throughout the United States on a daily basis. Some of these towers are upwards of 2,000 feet above ground and are some of the tallest structures in the world, posing a great danger to aircraft navigation due to their thin structure.

The FAA must approve construction of all towers higher than 200 feet above ground, but below that, no one knows where they’ll go up. These obstacles should be lighted at night but there is no set requirement (see Advisory Circular 70/7460-1K).

Methods of Wire Detection

Detecting wires and towers starts in the preflight. Not all wires and towers are charted, only the bigger ones, but the charts will still give you an idea of where you might find concentrations of obstacles. Power lines are often found along roadways as well, so assume that any roads on your chart may have transmission lines along them.

Remember that there aren’t any straight lines in nature! Vertical straight lines are towers and poles while horizontal straight lines indicate transmission lines and service roads. This is especially true of forested areas that have been cleared for transmission lines. Though you may not see the wires from a distance, you’ll definitely be able to identify the clearing in the trees!

And what about actually driving out to the site first? If you can perform ground reconnaissance of the area you’ll be operating in, you’ll be able to study the entire area at 0 AGL and 0 knots. Take your time, look at the area from all angles, and make a sketch if you have to. Where should you make your approach and departure? Which areas should you avoid flying a helicopter over?

Good aerial reconnaissance is essential before going low. It starts with a high recon, at least 500 feet above the landing zone (LZ). At this altitude you’ll be able to avoid all but the tallest transmission towers – you better know those guys are there before you go!

You need to fly a full 360 degrees while executing the high reconnaissance and don’t be shy about taking a couple of laps if you need to. Environmental conditions and different contrasting landscape elements can make towers and wires invisible from certain directions, while they may obviously stand out from other directions. Identify wires, towers, and other obstacles, and note safe flight paths and avoid areas.

When the high recon is complete, don’t make your approach just yet. Smaller wires and smaller obstacles may not be visible from the high recon, and they could kill you if you jump right into the approach. Descend to 100-200 feet above ground and make a low recon, doing the same thing you did on the high recon but making an extra effort to identify smaller wires and poles.

You should conclude your low recon with an approach flown at a speed slow enough to react to an obstacle you missed in your recon.

This helicopter pilot did not do proper recon!

Methods of Wire Avoidance

Don’t fly low if you don’t have to! This removes the danger of hitting something attached to the ground, as well as many other benefits. You should always be higher than wires and towers in the cruise phase of flight.

Don’t fly through spaces where wires could be strung. There’s this thing called “inferred wires”. Take the highest two points you’ll be flying a helicopter through and draw an imaginary line between them. Are there actual wires connecting the two points? You have to prove that the wires aren’t there before you invade that space. This is especially common in canyons. “Cowboy pilots” love flying a helicopter through canyons but many wire strikes occur here, even with wires that are marked with high-contrast wire markers. In fact, half of all wires hit are marked.

Fly over the towers, not the wires. If you just fly over the wires you may get into the false sense of security thinking that the biggest wires you see are the tallest ones. Typically, towers have thin static wires above the thicker transmission wires. Flying over the towers will prevent hitting these static lines.

Final Thoughts

If it’s too late and you do hit that wire, don’t give up! Keep flying the aircraft. Many pilots have successfully regained control of their aircraft and landed after a wire strike. It ain’t over til it’s over!

Do you have any other methods to add? Don’t become a statistic! Wires and towers are more common than you know, and they will kill you!

Robinson R44 Helicopter

The Robinson R44 helicopter is a four-seat follow-up to the highly successful R22 two-seat helicopter trainer, taking to the skies 15 years after its predecessor. When the R22 stole the market for two-seat helicopters, Frank Robinson moved to do the same with four-seat helicopters. Low operating costs of roughly $225/hr for the Raven II have helped make this possible. The first Robinson R44 helicopter to be produced was the Astro, certified by the FAA in 1992. This helicopter was in many ways just a larger R22 [Click to read more…]

The Robinson R44 helicopter is a four-seat follow-up to the highly successful R22 two-seat helicopter trainer, taking to the skies 15 years after its predecessor. When the R22 stole the market for two-seat helicopters, Frank Robinson moved to do the same with four-seat helicopters. Low operating costs of roughly $225/hr for the Raven II have helped make this possible. The first Robinson R44 helicopter to be produced was the Astro, certified by the FAA in 1992. This helicopter was in many ways just a larger R22 [Click to read more…]

How helpful that you talk about how there are so many wires in the US that pilots need to be careful of. My son wants to learn how to fly this winter. I will find him a great helicopter pilot flight training class in our area.