Despite his daredevil stunts and record-breaking accomplishments, Noel Wien always considered himself to be a cautious pilot.

History always has a place for the men and women who open up frontiers. Explorers, settlers and adventurers, these early pioneering souls tread paths that countless millions will follow down the line. In the 19th century, the American West was opened by pioneers who blazed trails with horse and wagon. And in the 20th century, it was airmen who opened the Alaskan wilderness. Held aloft by aircraft that were little more than wire and fabric, these men would tame the frozen north and join isolated communities. First and foremost among them is Noel Wien.

Moving to Alaska in his mid-twenties, Wien would dedicate the remainder of his life to providing air transport to the state, breaking records and establishing commercial routes as a matter of course. He was the first to Fly from Fairbanks to Seattle. He would venture beyond the Arctic Circle and across the Bering Strait. And he would join East and West with the first commercial flight between Alaska and Asia. All of these feats would earn him fame and epithets aplenty. He soon racked up nicknames such as “the Lindy of the North” and “The father of Alaska bush flying.” It is for these accomplishments and others that he would win an eternal place in the national aviation hall of fame. But to Wien, flying was a serious business. He was no glory hound. To him, it was all in a day’s work.

To this day, his Alaskan legacy lives on. Since he introduced the airplane to Alaska in the ’20s, it has a greater number of pilots and aircraft per resident of any US state. Alaska posed a serious transportation problem for its citizens. It is a vast space, encompassing more than twice the land of Texas. And that land is made up of almost impassable terrain and gripped by a less than hospitable climate. With a population that is dispersed thinly across that great expanse, Alaska desperately needed an efficient and fast transportation system. While railroads were slowly but surely expanding to span the territories, there were still many isolated areas. During an aviation career that spanned over 50 years, Wien would see the airplane become the most important means of transport.

Noel Wien’s Early Days

For a man who would have such a profound impact on the frozen north, it may be surprising to know that Wien was not born in Alaska. Born in temperate Lake Nebagamon in Wisconsin, Noel’s family moved to Cook, Minnesota when he was just 5 years old. Growing up on a farmstead, it would seem that Wien’s future would lie in farming. He even developed an aptitude for mechanical work, learning to service tractors and other farm machinery with expertise. But he never had a strong affinity for farm work.

Instead, it was aviation that would farm his imagination. First, in the form of stories he would hear of WWI aces and their accomplishments. And later through the daring stunts and aerobatics he would see at local county fairs. He was always tormented by the fact that he could see these planes at a distance, but could not touch them, or ride in them. This led him to decide to learn to fly as soon as he was able. And so it was that at the age of 21, with a pocket full of money and the determination to embrace a career in aviation, he left home for Minneapolis.

It was here that he would finally get to fly, first as a passenger and then as a pilot. His early training craft was a surplus WWI training plane – he was learning to fly in the same vehicle as his heroes. Wien was a fast learner, and he went from student to solo pilot in the space of a few months. Wien wasted little time in putting his pilot skills to use. By serendipity, his mechanical skills gained from servicing farm machinery would be put to good use, too.

Wien joined a husband and wife barnstorming team on a cross-country tour as a ground mechanic. After a while, he was flying the plane himself, and eventually, he was doing almost all the flying. It was a golden age for aviation, and all over the country, sporting clubs were springing up with members who were keen to receive expert instruction. Recognizing this need, Wien would move on to provide lessons to these early sportsman pilots.

He continued to fly with barnstorming groups, and would also try his hand at aerobatic flying for a flying circus. Within a few short years, Noel Wien had gone from an enthusiast with dreams of flight to a full-time professional daredevil pilot. In 1923, an event occurred that would shape his entire future although he was not aware of it at the time.

Noel Wien Heads to Alaska

A businessman in Anchorage realized the importance of aviation for Alaska and cleared a field in order to build the first airstrip for bush pilots. Later, this airstrip would expand to become the Delaney Park Strip. But in 1923, with barely a handful of pilots in all Alaska, this was an almost prophetic move. Of course, the businessman was not about to risk all on the hope that aviation would take off. And so he also used the airfield as a 9 hole golf course.

Hearing about the event, and recognizing the wide open potential posed by Alaska, Wien flew an open-cockpit Hisso Standard J-1 biplane to the new airfield. Wien chose this aircraft carefully and later commented that the engine configuration was the only option that suited the challenges posed by the Alaskan Climate.

Upon arriving, he busied himself with stunt flying to commemorate the new strip. He even named his plane “Anchorage.” During the first few weeks, he took thrill seekers for rides and performed for the crowds. But already he had set his sights on a bigger goal. His ambitions went beyond stunt flying and giving rides to enthusiasts; instead, he saw the potential of commercial passenger flight in a land where the main form of transport was by river.

With the help of a local mechanic (Mr. Gill), he modified his plane with an auxiliary fuel tank. This would give him the range for his first serious Alaskan flight, a non-stop flight from Anchorage to Fairbanks. In the middle of July, he took off for the flight with one passenger, a mechanic named Bill Yunker. The early stages of the flight were plain sailing – all he had to do was follow the train tracks.

But halfway through the flight, his luck turned. A fierce forest fire was filling the air with smoke, making it impossible to see the train tracks. In order to continue, he had to descend to 200 ft and fly at low visibility. Dangerous at the best of times, he had the risk of tunnels to consider. Without a reliable map, the only warning he would have would have been the shadowy form of the tunnel looming out of the smoke, and by that time it would have been too late. Fortunately, he was able to avert disaster and land safely in Fairbanks, setting the first of many records.

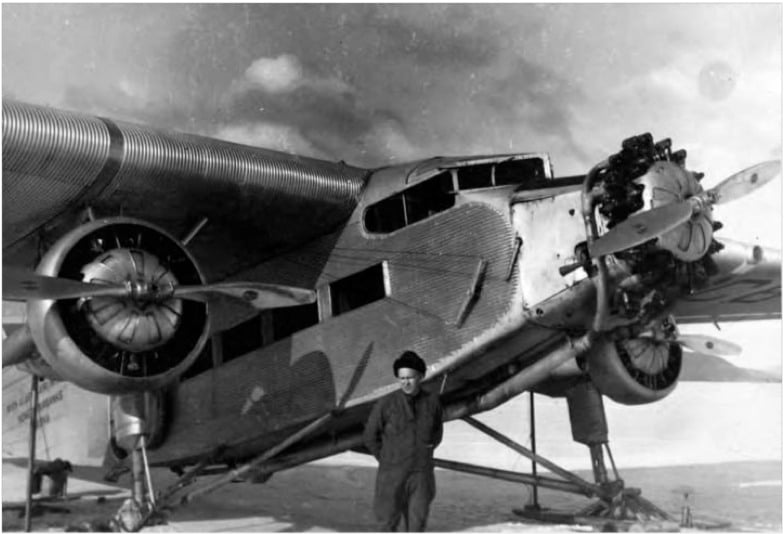

(Noel Wien Handprops his Hisso Standard J-1)

In fact, it was not until the following summer that he would have any competition. For the time being, he was the only pilot aloft in Alaska, and so almost every flight he would make set a new record. By the time any real competition would arrive, a few years later, he was already firmly established as a living legend.

Alaskans were fast to embrace air travel, even if they were a little wary at first. Unlike much of the US, Alaskans had little choice when it came to traveling. A trip to see loved ones or conduct business may mean a 2 or 3-week river trip. By air, the same journey could be taken in little over an hour. Early passengers included the wives of prospectors and miners. Hardly thrill seekers, they were more than glad for the chance to make the journey. The attitude was best summed up by a mining official named Norman Stein. Following the first commercial flight between Fairbanks and Nome, Stein commented that “It sure beats walking!”

Wien would go on to set records as the first pilot to fly north of the Arctic Circle, and was the first commercial pilot to work the Arctic Coast. He would set records for flying from Fairbanks to Seattle. He was the first to fly from the United States and Siberia via the Bering straight. And his commercial airline was the first to offer services year round, refusing to be grounded by hazardous winter conditions. All of this was accomplished at a time when maps were unreliable, aircraft radio was unviable, and there were few landing strips (and virtually none of them were paved).

And all of this before receiving his pilot’s certificate!

But this omission was soon remedied. Towards the end of 1925, he was granted his formal certificate (number 39), signed by none other than Orville Wright.

Without paved runways, Noel had to be good at landing. Very good. Through practice and necessity, he learned to land his Standard in just 300 feet. His expertise drew acclaim and praise from those he would fly. Surveyor Sam White would later say that his skill was so great that it was as if the wings had grown out of his own shoulders.

Wien Air Alaska

After his first year of commercial flight, Wien sent for his 3 brothers, to join him and expand the business. Ralph was the first to respond to the call and was later joined by Sig Wien and Fritz. Together, they would form Wien Air Alaska, which was the first airline in Alaska. In fact, it was one of the first in the entire United States.

Given the strong demand for air transport, it shouldn’t be surprising to learn that it was an immediate success. Within the first few months, the Wien brothers had made $4,000. The brothers immediately invested in another plane to expand their operations. The second plane was a Stinson Detroiter.

Despite his daredevil stunts and record-breaking accomplishments, Wien always considered himself to be a cautious pilot. He was not interested in risking all to win praise and glory. Instead, he possessed great skill and new how to assess risks. So if he appeared to be over ambitious in accepting hazardous flights, it’s important to realize he was confident in his ability to complete the assignment without harm.

So it was in the winter of 1929 when Noel agreed to fly 600 miles up the Siberian coast in order to recover a small fortune in fur from an icebound vessel. The pelts were pure white fox, with a value of $600,000. That the flight would see him facing temperatures of -40 degrees, blizzards, and fierce winter winds – these were mere details. Details which he had meticulously calculated and found acceptable.

And so it was that he completed the first commercial flight between North America and Asia.

There were many wild stories from this time. Some live only in legend, others were captured by biographers on in one of Wien’s rare recorded interviews. A Time magazine article from 1968 tells of his Misso Standard biplane delivering gold miners from Fairbanks to Nome. They also recount stories of pilots delivering babies while flying the plane with their feet. Doubtlessly, there are stories from this period which are lost to history.

What we do know is that in 1929, Wien married the daughter of the Nome postmaster. Her name was Ada Berin Arthurs, and together they would make a home in Fairbanks and raise 3 children, Noel Merrill, Richard, and Jean.

Jumping forwards to 1968, the airline he built was still thriving. Wien Air Alaska would merge with Northern Consolidated airlines. They then went public and raised funds to buy two Boeing 737s. Wien Air Alaska continued to innovate, piloting the use of jet planes on gravel runways. They experimented with different ways to convey cargo and passengers with their 737s.

Although Noel passed away in 1977, the company continued to expand, and in the early 1980s they had built a network which covered dozens of Alaskan towns. They extended from Point Barrow to Phoenix, Oakland, and down to Denver. They operated out of Anchorage and Seattle.

In 1985, the airline ceased operations. It left behind it a legacy of affordable air transport connecting communities throughout Alaska and the rest of the United States. But although the airline has wound up, the family continues the tradition of aviation. On July 6, 1999, Wien’s sons Merrill and Richard market the 75th anniversary of the historic Anchorage to Fairbanks flight by repeating it. In recognition of his lifelong service to aviation and the people of Alaska, Wien has truly earned his place in the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

He will always be the father of Alaska bush flying.

ADDITIONAL VIEWING:

If you’ve got some time (about 30 minutes), here’s an interesting four part interview series with Noel Wien, made in the 1960’s:

Thank you for posting this. Noel was my cousin.