Charles Lindbergh and The Spirit of St. Louis Cross the Atlantic

Hanging between the cloud-dashed sky and churning dark waves, Charles Lindbergh fought his exhaustion. He had been conscious for more than 40 hours, and his body craved sleep. Despite the bitter cold, the endless droning of his plane’s engine and the unbroken monotony of the seascape were lulling him to sleep.

But sleep was the one thing he could not afford. All alone in the Atlantic skies, surrendering would mean certain death. And so he struggled to stay awake. He ignored the food he had packed, despite his bitter hunger. He even flew dangerously low, hoping the stinging sea spray would keep him awake.

Navigating by the sparsely visible stars, he plunged into the ever-retreating horizon. His tormented nerves started to play tricks on him. He saw impossible ethereal islands of smoke. Semi-transparent phantoms appeared in his cockpit offering encouragement.

With a grim determination, he fought on. His flight had seen him cross over 3000 miles from New York. He had flown through rain, fog and ice.

If he had died that night in May 1927, he would not have been the first. The famed Orteig prize of $25,000 had drawn many aviators and WWI aces. Many of their attempts had ended in flames and wreckage. All had failed.

It was with considerable relief that he neared the airfield in Paris. A sea of bright lights surrounded the airport, and at first, he mistook it for an industrial complex. In fact, those lights were the headlamps of thousands of cars.

Over a hundred thousand spectators had come to see his arrival. They literally pulled him from the cockpit and carried him on their shoulders. And so Lindbergh was to spend another thirty minutes airborne.

Eventually a joint force of pilots, soldiers and police came to his rescue. He was unhurt, but The Spirit of St. Louis wasn’t so lucky. Eager souvenir hunters had torn chunks of linen from the frame. Fortunately, the damage could be repaired.

It was just a taste of things to come. Between waking up and finally falling asleep, he had gone from obscurity to international celebrity. He would always be the first man to fly from America to Europe. And the world would forever be smaller.

It was a historic accomplishment.

Charles Lindbergh and the Early Years of Aviation

What kind of man would live where there is no danger? I don’t believe in taking foolish chances. But nothing can be accomplished by not taking a chance at all. – Charles Lindbergh

Some people are obviously born to greatness. Their early years are a parade of achievements and thrilling adventures. This was not the case for Charles Lindbergh. Before finally dropping out of college, he had graced the halls of no less than 20 schools.

Despite being the son of a US Congressman, he had no great prospects or personal fortune to fall back on. What he did have was a passion for motorized transport and planes in particular.

In 1922, he took his first flight lessons with the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation. As they only had a single training plane, they could not afford to risk it in the hands of a student pilot. And so he never once made a solo flight at that school.

Later that year, he would take to barnstorming, but not as a pilot. Instead, he worked as a wing walker and parachutist. Terrified audiences would watch him capering in the air, but few new his name. He also found work as a mechanic, servicing the craft he longed to pilot.

He finally made his first solo flight the following year. Although he was confident in his skills, nobody would trust him with their craft. So he bought his own plane. With $500 he had set aside, he was able to pick up a surplus Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” biplane.

After a couple of weeks practice, he was ready for another round of barnstorming. This time, he flew under his own name – “Daredevil Lindbergh.”

After a few months of entertaining crowds, he joined the United States Army Air Service. They put him through a grueling year-long training program. The majority of the trainees bailed out before the end of the program, and only 18 students graduated from a class of 104.

The course was dangerous, and Lindbergh almost didn’t make it to the end. Just 8 days before graduating, he was involved in a mid-air collision. Both pilots managed to parachute to safety, but it was a close brush with death. Intact and undeterred, Lindbergh graduated at the head of the class. He had earned his pilot wings and a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant.

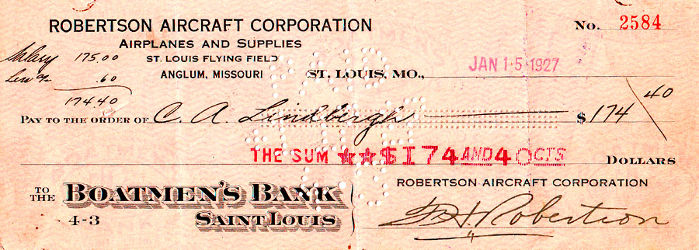

He put his new qualifications to use with the Robertson Aircraft Corporation. Starting in October 1925, he made the mail run between St. Louis and Chicago. The work was taxing, although it was not as dangerous as the training had been. He often had little time to sleep between flights, and would have to fly through the night.

His experiences as a mail pilot never gained him recognition or acclaim. But the endurance he built up would save his life during his record-breaking flight. He flew air mail until February of 1927 when he decided it was time to go after the Orteig prize. With $2,000 of his own money and a pair of loans, Lindbergh and his backers began searching for an airplane.

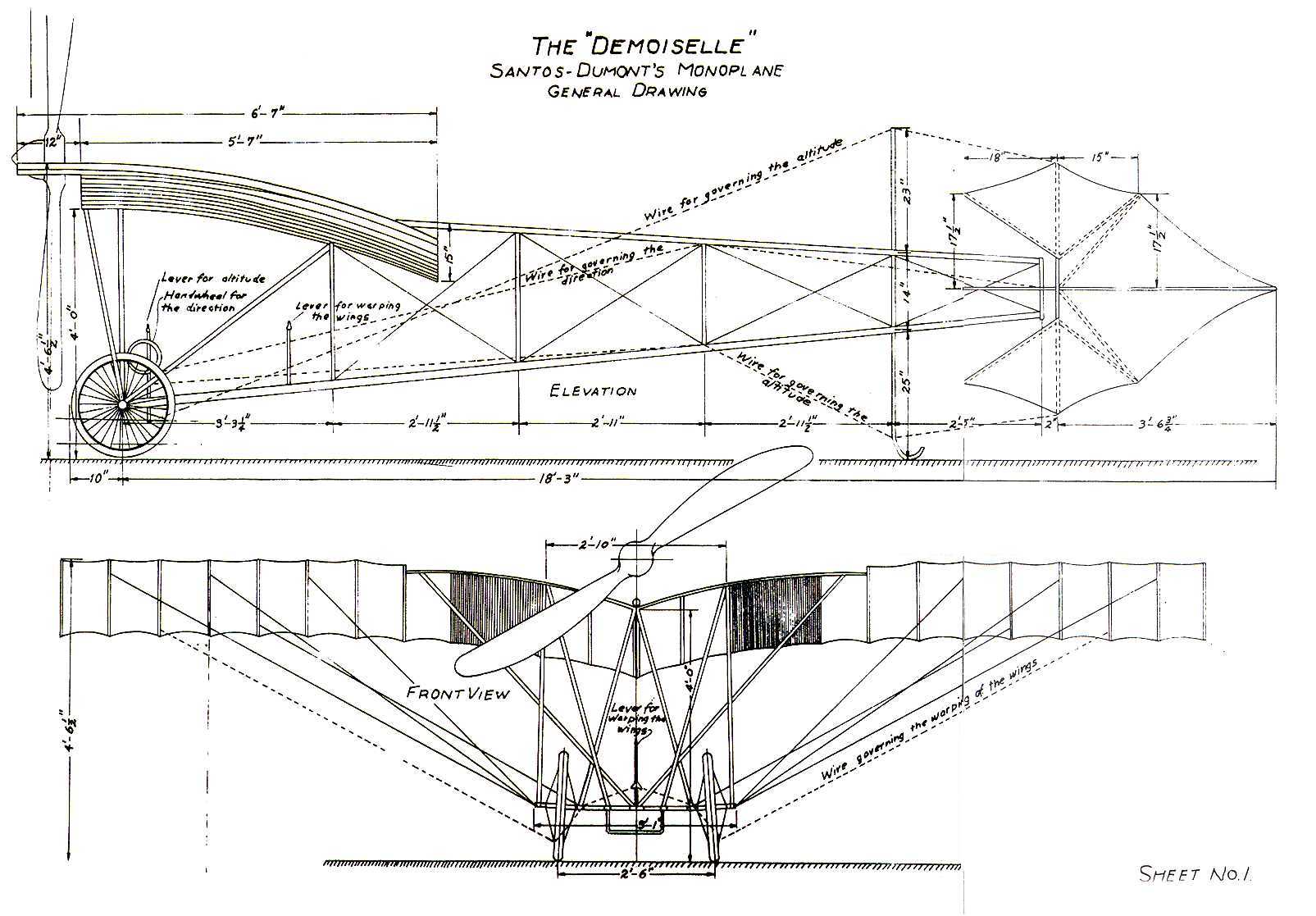

They first approached Wright Aeronautical in New Jersey, followed by Travel Air of Witchita and finally Columbia Aircraft Corporation in New York. All three aircraft manufacturers turned him down, stating they would not agree to a sale unless they were allowed to select the pilot. Finally, the Ryan Aircraft Company on San Diego agreed to design and build Lindbergh a monoplane from the ground up, for a cost of $10,580. A deal was struck on February 25th, and a mere two months later, on April 28th, The Spirit of St. Louis flew for the first time. Not even a month later, on May 20th, Lindbergh lifted off from Roosevelt Field, on New York’s Long Island, pursuing a prize that had already claimed the lives of six famous aviators.

It is the greatest shot of adrenaline to be doing what you have wanted to do so badly. You almost feel like you could fly without the plane. – Charles Lindbergh

Charles Lindbergh and Life After Crossing the Atlantic

When he crossed the Atlantic, he expected to make a stir. But he had no idea how big it would be. The next few weeks were a dizzying round of public and official praise and adulation.

It started in Paris, where government buildings raised the US flag in his honor. It was an honor reserved for heads of state. Then Gaston Doumergue (the President of France) decorated Lindbergh with the Légion d’honneur. It was the highest possible recognition.

When he returned to the US a fleet of warships escorted him up the Potomac River. Military aircraft filled the sky, from pursuit planes to bombers. Among them was the immense USS Los Angeles, a dirigible which had been recently constructed by the Zeppelin company.

Shortly after arriving on US soil, Lindbergh was decorated by another president. This time, it was President Coolidge, and the medal was the Distinguished Flying Cross. The US Post Office Department paid its respects, too. They issued a special airmail stamp featuring Charles and The Spirit of St. Louis.

During the next few days, Lindbergh was hounded by the press and well-wishers. Radio shows, newspapers, and magazines wanted to interview him. Companies, think tanks, and universities all wanted a slice of the glory. To a man who valued his privacy, it was almost too much to bear.

On June 13, the mayor of New York held a ticker-tape parade in his honor. Lindbergh’s discomfort was palpable in the photographs. That night, the mayor’s Committee of Receptions held a banquet in his honor. It was at this event that Orteig presented the $25,000 check.

It was clear to Lindbergh that he had the world’s attention. He decided to use it to highlight issues important to him.

When it came to aviation, his word carried a lot of weight, particularly with the public. And inspiring the public was important. Civil aviation had been struggling to overcome the hurdle of public skepticism. Following Lindbergh’s flight, the demand for air transport shot up. He also campaigned to promote the use of air mail. He inspired the public, and they breathed life into the budding aviation industry.

His contributions to aviation were not just rhetorical. He made several practical contributions, too. He charted routes in the Arctic and South America. He developed new flying techniques to conserve fuel and increase range. These techniques would later play an important role in the Second World War.

He even helped to raise funds for Robert Goddard’s rocket research. They saw rocket propulsion as the future of aviation, and even space travel. Thanks to Lindbergh’s support, the Guggenheim family provided Goddard with $100,000 in funding.

Recognizing his initiative, the president appointed him to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

Charles Lindbergh and the Crime of the Century

His position in the public eye gave him the power to champion important causes, but it also brought unwanted attention to his family. And ultimately, it led to a terrible tragedy.

On March 1, 1932, the Lindbergh’s 20-month-old son was taken from the family home. The kidnapper entered the home through a second story window and grabbed the child from his crib. The police response was fast but ineffective. Despite a 10 week nationwide search, they were unable to find the Lindbergh baby.

The kidnapper contacted the family with a ransom demand. He wanted $50,000 in exchange for the child. Lindbergh paid the ransom and was given instructions to find his son. The information turned out to be a lie. The Lindbergh’s despaired of ever seeing their son again. And then came the cruelest blow.

Their son’s remains were found in a small wood near their house. He had been murdered shortly after the abduction.

After almost a year without results, the police were contacted by a suspicious gas station attendant. A man had paid for gas using gold certificates, which were no longer issued. Lindbergh had paid the kidnapper with gold certificates for this very reason.

Following the description from the attendant, the police arrested Bruno Hauptmann. Searching his property, they found $13,760 from the ransom money. In spite of the evidence stacked against him, Hauptmann claimed he was innocent. He continued to plead innocent during his trial. He was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Charles was a seasoned public figure and had plenty of experience with the press. But he was shocked and appalled by their morbid interest in his son. Reporters hounded his family to exploited their grief. In disgust, Charles took his family overseas, calling America a primitive and undisciplined society.

For 3 years, they lived in England, before visiting the continent to tour the capital cities. Although Europe was at peace, the specter of war was in the air. The flames of ideology and greed were growing. Soon, these same cities would be gutted by aerial bombardments.

Charles Lindbergh and World War 2

The threat of war was felt in the United States, too. Although there was a strong opposition to war, the military had to prepare. General H. H. Arnold contacted Lindbergh and asked him to return to America. His experience would be vital to the US Army Air Corps. And so, in 1939, the Lindbergh family returned to New York.

Returning to active duty, Lindbergh brought his experience and knowledge. He evaluated new aircraft designs and helped to plan new training and research facilities. He even helped with recruitment. He dedicated a lot of time and energy to ensuring America’s air services would be ready for war. But he also made a public stand against fighting Germany. This stance would lead to several public clashes with president Roosevelt.

In fact, he became a major thorn in Roosevelt’s side. As an outspoken proponent of the America First movement, Lindbergh had the ear of the public. He claimed that without Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia would sweep across Europe. The fear of communism was strong at the time, and this argument struck a chord with his listeners. Roosevelt was not impressed; he believed that Lindbergh was a Nazi sympathizer.

Lindbergh’s public support of Eugenics and racial purity were a matter of public record. And he had accepted a medal from Hermann Göring when he visited Germany. Publicly, Lindbergh said he deplored the brutality of Nazis. He was especially against their intolerance of Jewish people.

There were accusations that Lindbergh was anti-semitic. He was a close friend of Henry Ford, and together, they had discussed Ford’s theories about the “Jewish Conspiracy.” Lindbergh was also suspicious about Jewish influence in the American press, entertainment, and government. He denied that his views were anti-semitic.

When Roosevelt accused Lindbergh of being a defeatist and an appeaser, it was more than Charles could take. He resigned his commission in anger. Roosevelt later blocked Lindbergh’s efforts to enlist when America entered the war.

Unwilling to stand back and wait out the war at home, Lindbergh found a “loophole.” He offered his services as a civilian consultant to United Aircraft. They sent him to the Pacific theater, where he was to act as a technical advisor. In this capacity, he had to study the performance characteristics of new aircraft.

Of course, to inspect the aircraft properly, he would have to gain some hands on experience. And so, Lindbergh managed to talk his way into flying real combat missions. By the end of the war, he had flown over 50 combat missions as a “civilian.”

Roosevelt may never have forgiven him, but America did. In 1954, Eisenhower recognized his wartime contributions. He gave Charles a commission as a Brigadier General in the US Air Force.

After the defeat of the Third Reich, much of Eastern Europe had fallen to Soviet forces. In a sense, Lindbergh’s early assessments were proven right. But when he saw the extent of the Holocaust, he realized that the war had been necessary.

Here was a place where men and life and death had reached the lowest form of degradation. How could any reward in national progress even faintly justify the establishment and operation of such a place? – Charles Lindbergh

The Legacy of Charles Lindbergh

His early recognition of the potential for rocket-powered spaceflight was eventually vindicated. Apollo 8 sent the first men to the moon, forever proving the value of rocket propulsion. It was the fruition of Goddard’s dream, which Lindbergh had shared.

After a life dedicated to flight and technology, Charles turned his mind to other things. He dedicated his last decade to conservation. On August 26, 1974, he died from lymphoma aged 74.

Every day, thousands of air passengers cross the Atlantic. They soar peacefully above the churning waves, well fed and rested. They follow a trail blazed by Charles Lindbergh.

If one took no chances, one would not fly at all. Safety lies in the judgment of the chances one takes. That judgment, in turn, must rest upon one’s outlook on life. Any coward can sit in his home and criticize a pilot for flying into a mountain in fog. But I would rather, by far, die on a mountainside than in bed. Why should we look for his errors when a brave man dies? Unless we can learn from his experience, there is no need to look for weakness. Rather, we should admire the courage and spirit in his life. What kind of man would live where there is no daring? And is life so dear that we should blame men for dying in adventure? Is there a better way to die? – Charles Lindbergh

ADDITIONAL VIEWING: For those with a little extra time, National Geographic produced an excellent hour-long special on the life of Charles Lindbergh, entitled Across the Atlantic: Behind the Lindbergh Legend.

In the DOF Pilot Shop:

The Spirit of St. Louis, motion picture starring Jimmy Stewart.

Lindbergh, the highly respected New York Times bestselling biography by A. Scott Berg.

The Aviators: Eddie Rickenbacker, Jimmy Doolittle, Charles Lindbergh, and the Epic Age of Flight, by Winston Groom

The Spirit of St. Louis, Charles Lindbergh’s pulitzer prize winning account of his flight.

Thanks for the article, and for citing your sources, which sets a beautiful example for people these days. Your account of Lindbergh’s life inspired me.