All about the beacon system and aviation navigation arrows that used to guide pilots across the country.

File Under: Aviation History

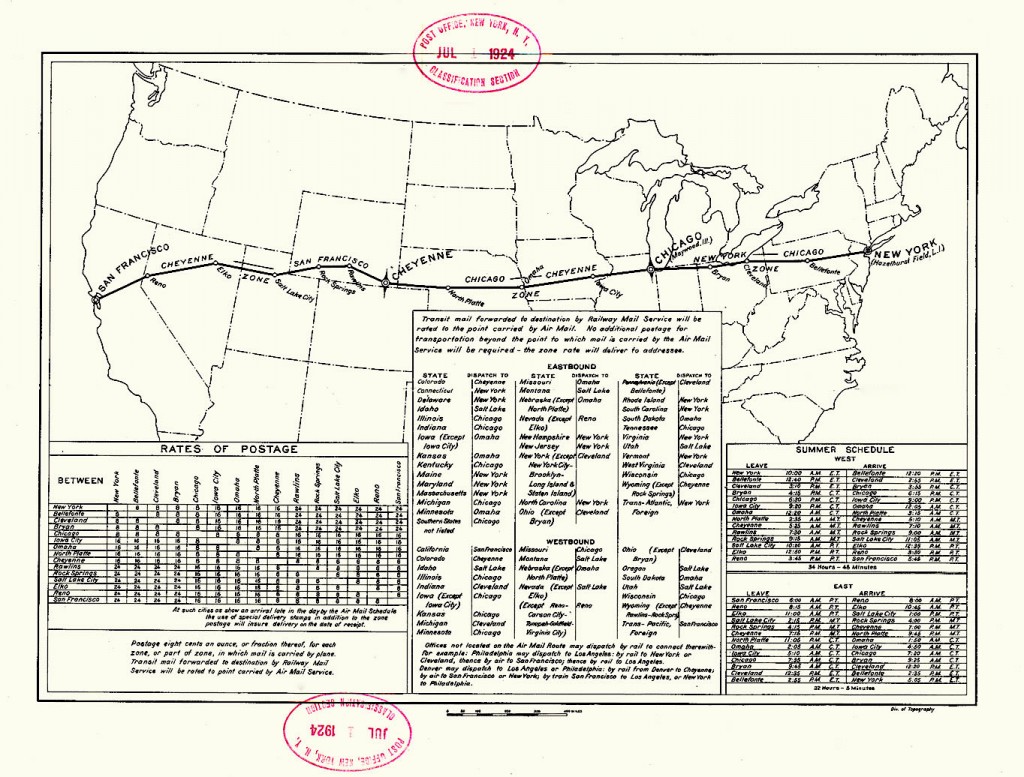

Our present is littered with remnants of technology from the past; vestiges of either attempts at achieving something new, or the very first form of a new technology. One of the more recent and fascinating occurrences is our first attempt at GPS for pilots. The year is 1924, and the US Government has decided that they are going to create a coast to coast aerial mail delivery route. The current hybrid system, with mail traveling by air during the day and rain in the evening, can deliver a letter in roughly 83 hours, and the Government feels like they can do better. Their problem? How to help pilots navigate their way across the country, especially during the night. Without reliable aviation charts, radio communication still in its infancy, and nothing like radar in sight, they decided on a rather straightforward and (in retrospect) somewhat comical solution: flashing beacon towers and giant concrete aviation navigation arrows.

The plan was to build a series of these towers and arrows stretching across the country, from New York to San Francisco, roughly every ten miles. After receiving funding from Congress, the US Postal Service* began construction on these arrows and beacons in 1924. The beacons consisted of two rotating lights that put out about 1,250,000 candlepower. These beacons sat atop steel towers, ranging from 21 to 80 feet in height. Each tower was constructed on or at the base of the arrows, which would point toward the next arrow/beacon tower in the route. The arrows themselves were usually 50 to 70 feet in length. The towers were painted and the arrows were bordered with bright colors (yellow and black or orange and white) to make them easily visible from the sky.

By the end of 1924, the arrows and towers stretched from Rock Springs, Wyoming, all the way to Cleveland, Ohio. By the summer of 1925, the arrows reached all the way to New York, and by 1929, they had completed a route that spanned the continent in an uninterrupted line.

And by 1933, there were 1,550 beacons and towers, that lit 18,000 miles of airways across the country. These lighted airways reduced the previous 83 hour delivery time to roughly 30 hours. In this photo from 1926, the mayor of Los Angeles is preparing to send an oversized letter to the mayor of New York City celebrating this fact.

This system was key to mail delivery and aerial navigation across the country for close to two decades. During this time period, the air mail system developed from a solely Government enterprise into an enterprise where the Government contracted with commercial carriers to deliver the mail. This led to the ‘Airmail Scandal’** of 1934, which ended the CAM (Contract Air Mail) routes in place, and returned the delivery of mail back into the hands of the US Post Office. And though Airmail, as a distinct service, wasn’t ended by the Post Office until May 1st, 1977, the lighted beacon system became obsolete in the early 1940s, with the rise of effective and widespread radio communication and navigation.

With the beacon system now being basically reduced to a cost-sucking drain*** for the government, the beacons were turned off, and many of the steel beacon towers were torn down, with the steel being re-purposed for the war effort. And though some of the towers and arrows were saved due to preservation efforts, such as this one in western New Mexico:

(For more information on the restoration efforts for this tower, visit: //www.cibolahistory.org/aviation-heritage-museum.html)

Though most fell into disrepair:

And now, some 70 years later, these giant concrete arrows litter the landscape, confusing outdoor enthusiasts and aviators alike. So the next time you’re wandering through nature, and you come upon a massive concrete arrow, stop for a moment, and take in the wonder of the first US GPS system.

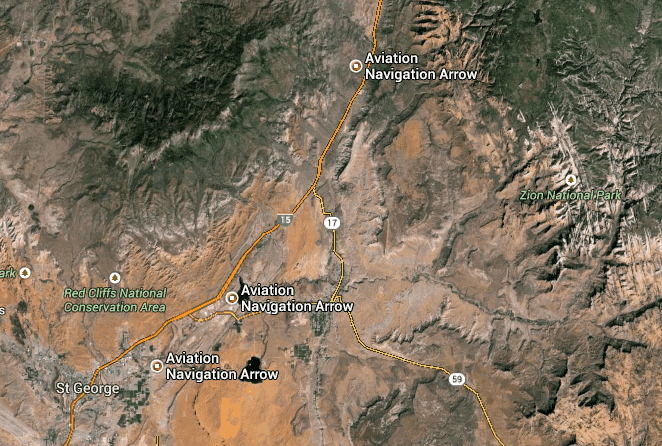

For those interested, here are some Google Maps photos of three of the arrows still visible from the air, and findable on foot in Southern Utah.

Washington County Aviation Navigation Arrow:

St George / Washington Aviation Navigation Arrow:

Hurricane Aviation Navigation Arrow:

* In 1926, the Post Office handed off construction and upkeep of the beacon system to the US Department of Commerce, as the air routes were leading to the development of modern day airlines, and the Post Office wanted to focus on delivering the mail.

** This scandal is a fascinating story, but because of its complex nature and far-reaching effect, it is, as they say, a story for another time.

*** Here is a look at the approximate cost of operating one of the beacons and aviation navigation arrows, according to a 1928 issue of Popular Aviation:

Flat Costs:

Beacon Light: $475.00

Automatic Lamp Changer: $50.00

Lamps: $6.50 (good for roughly 60 hours of use)

Monthly Costs:

Electricity: $50.00 – $80.00

Station Maintenance: $5.00

Land Rental: $.50

All of this worked out to roughly $110 a month (about $1,500 a month adjusted for inflation) in operating cost for each and every station. With 1,550 stations, the Government was shelling out $170,500 a month (or $2.32 million adjusted for inflation) just to keep the beacon fires burning.

Very Interesting story!