World War 2 Flying Ace Arthur Chin’s story is an incredible story of courage and survival during wartime.

Acquaintances commented in his later years that it was difficult to tell his age; most of his face had been burned away and the scar tissue now covering it was smoother than his natural skin would have been. He had been movie-star handsome, but about all that was left of his original face were his eyes, protected from the inferno by his goggles. How did those eyes keep their twinkle?

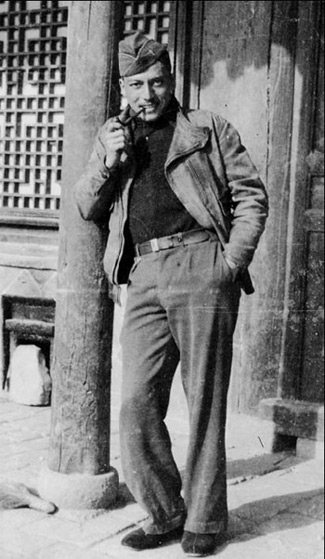

Especially after all he had been through – frustrations; crashes, defeats; after his first wife had died in his arms, shielding his terribly wounded body from Japanese bomb fragments? Yet, after all that, he had stood erect at a microphone in New York, with then-superstar George Raft by his side, campaigning for war bonds, posing for photos with his pipe jutting out at a jaunty angle. And when he was well enough, he went back to flying, this time in transports over the Himalayas, on a route so dangerous that it became known as the “Aluminum Trail” because of the hundreds of airplane wrecks that marked its course. Born and raised in America, Art entered history as an ace fighter pilot of the Chinese Air Force with eight air-to-air kills to his credit, all achieved in the skies of China before his own country officially entered World War 2.

Crossing the Pacific to Save China

Arthur Tien Chin (“Art” Chin as he was known) was born on October 23rd, 1913, to Fon Chin (from Taishan, Canton, China) and Eva Wong (possibly of Peruvian descent), and grew up in Portland, Oregon. Despite her name, his mother was listed on his birth certificate as “mulatto,” and, as a guess, may have been from Macao.

In the early 1930s, echoing the call of “Saving China by Aviation” by Sun Yat-sen, Art and a number of other promising young Chinese-American pilots entered flight training with the Al Greenwood flying school in Portland, his tuition and fees being paid by the local Chinese community. This is especially significant because flight training was expensive,i making this a substantial sacrifice. The Japanese Empire was on the march in Asia, and its annexation of Manchuria in 1932 simply confirmed the suspicions of many about Japan’s designs on China. Determined to save their ancestral homeland and buoyed by the best wishes of their neighbors and friends, Art and eleven other young Chinese-Americans set forth in 1933 to volunteer to fly for the Chinese Air Force.ii

They ran into a brick wall, figuratively speaking. Unfortunately, the central government was not interested in their services. Although details aren’t available, it seems likely that this was a case of the bureaucracy facing a situation without precedent or instructions and being unwilling to make a decision. Although China was seeking help from abroad it hadn’t solicited this particular assistance from these particular people. Added to this was their status as Overseas Chinese, which, to many, implied suspicious links to foreign powers (much as it did, ironically, in their countries of residence). Although, taken in isolation, this would seem to be little short of paranoid, there were some legitimate grounds for general mistrust.

In certain respects Japan was just one of several forces vying for power in China at that time. The 1911 Revolution that signaled the end of the Qing Dynasty had not led to the firm establishment of a successor regime and, despite high hopes for Sun Yat-sen’s Republic, China had fragmented into a patchwork of chiefdoms headed by warlords. By 1930, Sun’s party, the Kuomintang (KMT – by then under Chiang Kai-shek) had suppressed most of these warlords and established a central government widely recognized internationally, but many provinces offered only token allegiance and groups such as Mao Tse-tung’s Communists still remained to be dealt with.iii

Oddly, this situation gave Art and most of his colleagues a “back door” into the air force. By the early ’30s there had been something on the order of sixteen separate air forces in China, ranging in size from one or two airplanes to a nominal strength of several hundred.iv Through much of the decade there were five besides that of the central government: those of Guangdong province (in which Canton is located), Guangxi province, Shanxi province, Sichuan province, and Yunnan province.v Perhaps because of their Cantonese ancestry, most of the Americans who were finally accepted started out flying for the Canton Air Corps of Guangdong. This was the largest and best-equipped of the provincial air arms, serving as “top cover” for Chen Chidang, the de-facto warlord of Guangdong. Art was one of these, being accepted as a Warrant Probationary Pilot on December 1st, 1933.vi In stark contrast to the pilots of the later American Volunteer Group (that was formed eight years later and existed for less than one year), who were paid $500 a month, their pay was equivalent to $25 US per month!vii

Craig Chinn provided an anecdote about Art‘s recruitment: “Back in the early 1930’s Harold [Harold Chinn, Craig‘s father] and Art went to the head of the Canton Air Force (Renee’s [Renee Robertson‘s] father Gen Arthur Lim) looking to join. Gen Lim told them their pay would be $25 (can’t remember the amount exactly) and they would have to buy their own uniforms. Both of them looked at each other, turned around and started walking out. Gen Lim then barked out to them and said, ‘What do you want to do? Go back to America to be laundrymen?’ They joined up.”viii

Art “enlisted” in the national air force during the summer of 1936. In a bid for power, Chen Chidang revolted against Chiang Kai-shek that May. Perhaps motivated by the sense that China needed unity in order to face the threat from Japan, in June and July of 1936 the Canton Air Corps defected as a group to the central (KMT) air force (the role in this of American pilots such as Art is not clear, but they don’t appear to have been the instigators). This was more than simply a shuffle of allegiances: Cantonese pilots actually flew all of their planes to KMT airfields. At a stroke the national air force was substantially augmented, and, as might be expected, the revolt fizzled.ix

Another major event in 1936 was Art and four other pilots being selected for advanced flight training, ironically in Germany with the nascent Luftwaffe. This may seem odd in light of the World War 2 German-Italian-Japanese Axis, but during the 1930s China was a major arms purchaser from Germany and relied on the Germans for advice and training in many military specialties.x The course was conducted at the historic Lager Lechfeld airfield in Bavaria, at that time used by the Bavarian Aircraft Works, manufacturer of Messerschmitt-designed aircraft such as the Me-109 and Me-110.

On his return from Germany Art flew as a flight leader with the 6th Squadron and then from February until June, 1937, as an instructor. That month he was assigned to the 28th Pursuit Squadron, 5th Pursuit Group, as Vice Squadron Commander under another American, Captain Chan Kee-Wong.xi The 28th was equipped with Curtiss Hawk II biplane fighters, an export model of the US Navy’s F11C-2 (in 1934 re-designated as the BFC-2).xii China had purchased fifty of these in 1933, the same year it went into service with the US Navy, but only four years later the design was already long in the tooth. It was an open cockpit, fabric-covered biplane with a fixed landing gear and armament of two rifle-caliber machine guns.

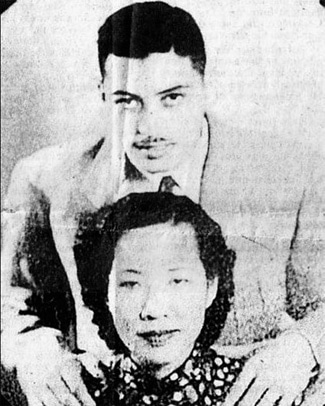

Life in China wasn’t all preparation for war. Handsome and outgoing, Art sported a classically pencil-thin mustache and smoked a pipe. Reputedly one of his few social impediments was speaking Cantonese with a pronounced American accent, but he had enough charm to overcome that. He developed a reputation as something of a ladies’ man, one that would follow him the rest of his life. Nevertheless, about this time he met and married a Sumatra-born ethnic Chinese named Eva Wu (Ng Yue-ying in Cantonese). According to Chin family tradition and some Chinese sources,xiii Eva was the daughter of the illustrious Wu Tingfang (1842-1922); first Chinese barrister in Hong Kong, Minister (ambassador) to the United States, Peru and Cuba during the periods 1896 to 1902 and 1907 to 1909, Minister of Justice and later of Foreign Affairs in 1912, and Acting Premier of China in 1917.xiv Eva and Art had two children, Gilbert and Steve.

Meanwhile, friction with Japan’s Kwantung Army escalated into open war on July 7th, 1937. On August 10th the 17th and 28th Pursuit Squadrons were stationed at Chuyung Airfield near Nanking, capital of the central government. The 17th was commanded by still another American, John Wong, and was equipped with the export version of the Boeing P-26 “Peashooter,” the Boeing 281. Although it was an all-metal monoplane, the P-26/Model 281 was a transitional design and retained many old-fashioned features.xv Even so, China was happy to have it. On August 13th Japanese forces attacked Shanghai and began their drive inland to the capital.

Combat

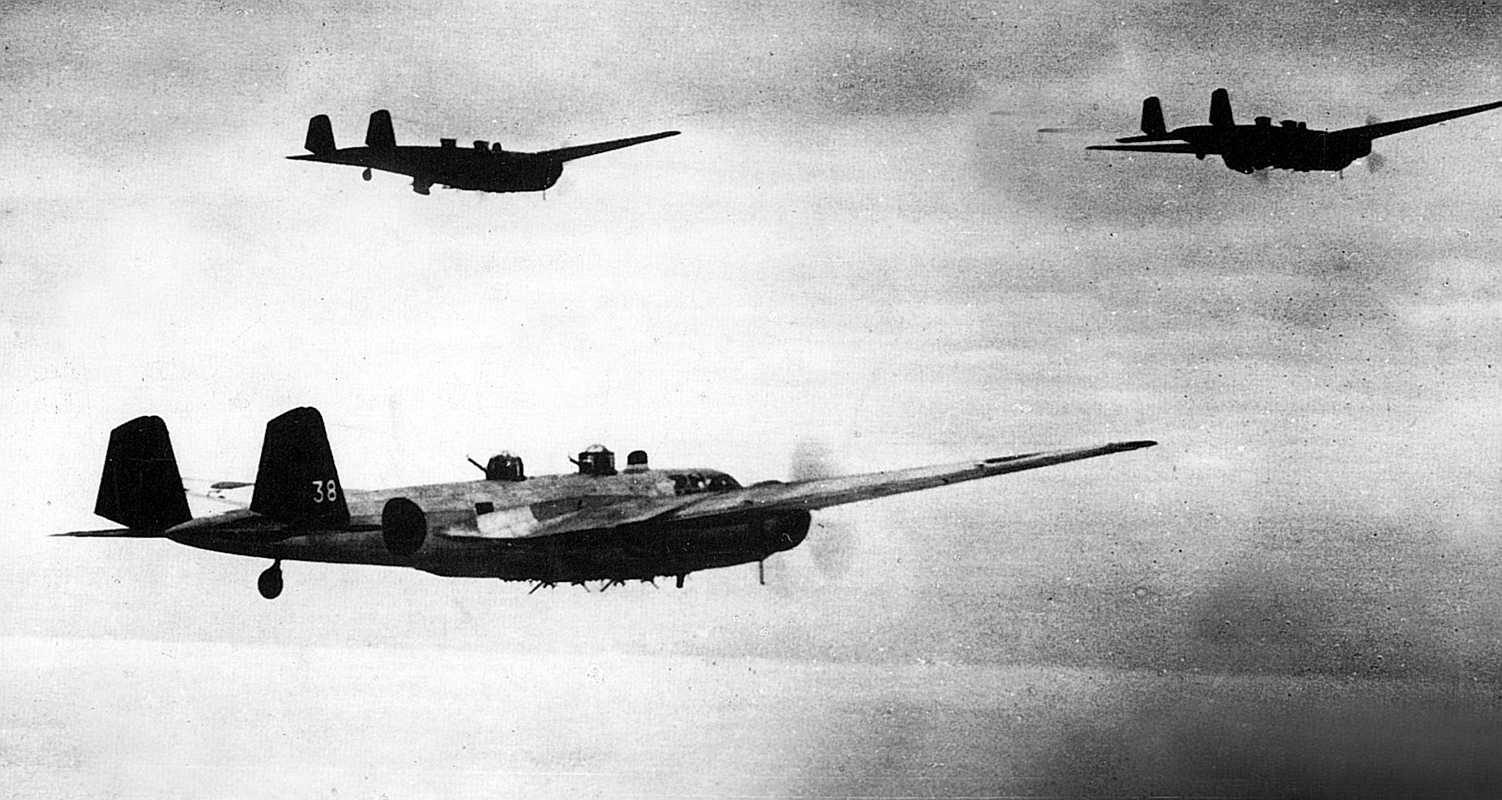

Art made his first kill, a Mitsubishi G3M2 twin-engine bomber, on August 16.xvi It was a difficult combat for him for a number of reasons, not the least of which was that his fighter wasn’t much faster than the bomber (if at all). According to researcher and personal friend Raymond Cheung, Art recalled that once he was in firing position he was virtually a stationary target for the bomber’s gunners. This combat highlights the rapid pace of aeronautical development during the 1930s. Although fielded only a few years apart (1933 and 1936 respectively), the Hawk II and G3M2 came from different generations. The Hawk II would not have looked out of place in a lineup of WW I aircraft, while the G3M2 was state-of-the-art: an all-metal monoplane with an enclosed cockpit, retractable landing gear, and defensive armament in rotating turrets. Although itself obsolescent by the beginning of the broader Pacific War, the G3M’s performance was still good enough for it to play a major role in sinking the HMS Repulse and the Prince of Wales off Malaya on December 10th, 1941.xvii

The 28th PS detached a flight to defend the Shaokwan Aircraft Factory in Canton Province, and Art was selected to command it. On September 27, 1937 his flight and one from the 29th (they being mounted on retractable-gear Hawk III’s) intercepted three G3M2s. Art didn’t claim a kill, but Japanese records show that one bomber was forced to ditch on the way back to its base and evidence suggests that he was responsible for the major part of its damage.xviii

The following month China obtained 36 Gladiator Mk. I’s from Britain. The 17th, 28th, and 29th Pursuit Squadrons were re-equipped with this type and worked up on it during January and February, 1938.xix The Gladiator was a step up from the Hawk II, being faster, armed with four machine guns, and featuring an enclosed cockpit, but it was still a fabric-covered biplane with fixed landing gear and an enormous, two-bladed wooden propeller. Like most fighters of the time it also lacked the armor and self-sealing fuel tanks which would come to be seen as so vital later on.

Art went on to score most of his kills while flying this type of aircraft, but on the flip side crashed three of them. The only loss that can be chalked up as an accident occurred on February 9, 1938. While leading a flight to Nanchang he ran into a snowstorm. This being an era before GPS – and even before a comprehensive net of radio navigational aids had been established in China – fighter navigation was primarily by pilotage. Leaving his flight above the murk, Art descended to see if he could locate some recognizable landmarks. As anyone who’s ever been out in a snowstorm can attest, the ground and sky tend to blend together. Art flew into a snow-covered hill. Miraculously, although the airplane was totaled he suffered relatively minor injuries, the most serious being below his right eye.xx

It seems obvious to say that an airplane crash is a traumatic event, especially when personal injury is involved. Some have quit flying after so much as witnessing one. Art’s only interest, however, seems to have been getting back into the fight. By the end of May he had recovered enough to be back in action, shooting down a Nakajima E8N floatplane. In June he was appointed to command the 28th squadron and promoted to Captain.xxi On the 16th of that month he scored a victory over another G3M2. In one of those eerie coincidences that occur in wartime, on the second day of August Art’s ground crew installed armor salvaged from a Russian-built fighter in his Gladiator. This would prove to be crucial in the events of August 3rd.xxii

On this date, Art is reported to have engaged three Japanese Mitsubishi A5M (probably A5M4) fighters by himself. According to Claire Lee Chennault – later of “Flying Tigers” fame but at that time an advisor to the Chinese Air Force – Art “deliberately rammed the Jap leader as he came in for the kill. Both planes burst into flame but Art hit the silk safely. . . . He was wounded and slightly burned, yet when we found him he was directing the salvage of the precious machine guns from his wrecked plane.” Art presented one to Chennault with the request: “Sir, can I have another plane for my machine gun?”xxiii

Although exaggerated somewhat, the basic outline of this story appears to be accurate. According to the best available account, the A5M that Art rammed was one of three that were taking turns shooting his Gladiator up until it was almost uncontrollable. He could hear bullets ricocheting off the (newly installed) armor plate behind his seat and, realizing that the time had come for desperate measures, rammed one of his adversaries. He barely managed to bail out of what was left of his own aircraft as it tumbled toward the ground, but landed safely and was taken to an aid station. A soldier brought him a machine gun salvaged from his Gladiator, and when Chennault visited him, Art joked about getting another airplane to go with it.

The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Mitsubishi A5M Type 96 was primary fighter faced by Art and his colleagues during this time. Designed by Jiro Horikoshi (who also designed its better-known successor, the A6M Type Zero), it was another 1930s transitional design, with an open cockpit, fixed landing gear, and armament of two machine guns.xxiv However, it was also an all-metal monoplane, faster than any fighter China had except the Polikarpov I-16 monoplane, and flown by superbly trained pilots.

In October, 1938, the surviving Gladiators were withdrawn for overhaul and the 28th Pursuit re-equipped with . . . still another biplane, the Russian Polikarpov I-15Bis (or I-152).xxv Decimated by accidents and enemy action, the Chinese air force had declined to a fraction of its former strength despite an infusion of Russian aircraft and reinforcement by Russian “volunteers” that had begun as early as the autumn of 1937. Fast twin-engine Tupolev SB bombers, and fighters such as I-15Bis and I-16, became mainstays of Chinese airpower.xxvi

On December 20th, 1938, Art was appointed Deputy Commander of the 3rd Pursuit Group.xxvii It appears that, like the rest of his comrades in the 28th, Art qualified in the Russian fighters but he didn’t claim any victories while flying them. When a Gladiator became available (only three appear to have been returned to service) he went back to his old mount. On November 2nd, 1939, Art and a wingman attacked a Mitsubishi Ki-15 reconnaissance aircraft – because of its speed considered by the Japanese to be virtually immune to interception by Chinese fighters – but didn’t down it. According to Art’s personal account he set up the kill by silencing the Ki-15’s gunner, but his wingman failed to follow through. Later that month Art claimed a twin-engine bomber, probably a G3M2, which he downed by diving below and attacking from the blind spot beneath its tail.xxviii (Early-model G3M2s had a gun in a retractable “dustbin” ventral turret that covered attacks from this angle, but it created so much drag that crews were reluctant to lower it unless they really had to. Later-model G3M2s dispensed with it entirely, depending on guns in waist blisters. This installation reduced drag but couldn’t cover an attack from directly below and behind the aircraft.)

Art’s combat career ended in a suitably climactic fashion on December 27, 1939. On this date he led a mixed formation consisting of an I-15Bis and another Gladiator escorting three Russian-flown SB bombers on a raid against the Japanese Army in the vicinity of the Kunlun Pass. After a savage fight during which Art’s flight fell one by one but appear to have shot down two Japanese fighters and damaged a third in return (personal credit for the kills is not certain), Art’s Gladiator was hit in the fuel tank and caught fire. He nursed his flying inferno back over Chinese lines and bailed out, but was terribly burned.xxix To compound his suffering, although rescued by Chinese soldiers he didn’t receive proper medical treatment for three days. Considering that infection is one of the worst dangers burn victims face, it is likely this was a factor in his difficult recovery.

The sacrifice was not in vain; all three bombers got through. After the bloody fight, KMT forces regained Kunlun Pass.

Carrying On

While recovering from his burns Art stayed with his family in a small house on Liuchow Airfield and was nursed by Eva. Unfortunately, only two days after Art’s return, the airfield came under attack by Japanese bombers. Eva took the children to the air-raid shelter first and went back for Art, who was virtually immobilized by the bandages over his face – including over his eyes – and on his hands and arms. In what must have seemed like a slow-motion nightmare they could hear the bombs exploding closer and closer. Too late to run, Eva threw herself on top of Art and was killed by shrapnel when the next explosion destroyed the house. During an interview many years later Art said simply “I held her dead body to mine until help came.”

Hong Kong, then a British colony, was neutral at that time. Art and his children were evacuated there where, in seven operations over two years, doctors at the Hong Kong Sanitarium in Happy Valley tried to repair the damage to Art’s face and hands.xxx In the chaos following the Japanese attack on December 8th, 1941, Art (still swathed in bandages) got out of his hospital bed, tracked down his boys – whose caregivers had either abandoned them or been killed – and managed to escape back across enemy lines to friendly territory. Finally, friends such as Chennault and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek (Soong Mei-Ling, wife of the Nationalist Chinese Generalissimo) persuaded Art to return to the States for treatment. As commanding officer of the “1st American Volunteer Group,” Chennault drafted a letter dated June 10th, 1942, requesting US air transportation for Art.xxxi At a hospital in New York, Art suffered a series of twenty operations over a period of twenty months to rebuild his face and hands, leaving him heavily scarred but reasonably whole.xxxii

According to Craig Chinn (who qualified his comments with: “a lot about Uncle Art’s grafts is hearsay from my parents”), “his skin grafts came from the back of his calves, upper arms and thighs. I recall him showing me the wide swaths of scarring from the removal of skin. We never paid attention to his facial features as that was Uncle Art.

. . . I recall my mother telling me that they took little hairs from other parts of his body to create eye brows. He never completed the facial reconstruction because it was very painful (1940’s medicine). He did not have any feeling where he had skin grafts. When eating he learned to constantly wipe his mouth since he could not feel if anything was rolling down or stuck there.”xxxiii

Clearly, Art had “done his bit” and no one could blame him if he had decided to rest on his laurels, retire to a quieter line of work, and hide his scarred face from the world . . . but that wasn’t Art’s style.

He spoke at war bond rallies and on radio broadcasts with such celebrities as movie star George Raft. A particularly notable event was the “Gung Ho” War Bond rally in New York, which was sponsored by Chinese-American community and attended by dignitaries including Mayor LaGuardia. “Gung Ho” is actually from a Chinese phrase meaning “Work Together,” and was a perfectly reasonable name for an organization and a rally to support the joint war effort of China and the United States.

Around this time Art met, charmed and married a nurse named Frances Murdoch. They had one child, a daughter named Susan. After the war, while sailing to meet Art in Shanghai, she fell in love with another passenger. The divorce was amicable, with Art asking only for the custody of the child.xxxiv

Over the Hump with CNAC

Finally, Art returned to duty as a transport pilot with the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC). He qualified for a Second class medical on March 28, 1945.xxxv This, and a letter signed by Major General P.T. Mowxxxvi that certified that he had 3000 hours of flight time from his service with the Chinese Air Force, launched his airline career. During the final stage of China-Japanese war, he flew supplies over the “Hump” route through the Himalayas from India into China. This was not soft duty. A former commander of USAAF portion of the airlift, Lt. Gen. William Tunner, later wrote that “flying the Hump was considered as hazardous as flying a combat mission over Germany.”xxxvii Sixty years later an estimated three hundred aviation personnel are still listed as missing in action in the region. xxxviii

At the end of the war Art stayed on in China to fly with CNAC, by then as a fully qualified airline captain. Captain Chin was certified as an Authorized Check Pilot for the airline on October 15, 1947,xxxix at which time he held single engine, multi engine, instrument and Airline Transport Pilot ratings. During this time he was specifically rated to fly DC-3, C-46 and C-47 aircraft.xl

During this time he met Vivienne Yang, then employed in CNAC’s Shanghai office. Vivienne had been warned by a coworker not to fall asleep while riding on a plane piloted by Art: “Don’t doze off, if Captain Chin wakes you and you open your eyes to see his face, you might get an awful fright!”xli Vivienne evidently was able to see beyond Art’s scars, and they married in 1948. Craig Chinn said of Vivienne that she “added a softer side to Uncle Art. She was quiet and very proper. I recall she was a great cook, with a Shanghai flair.”xlii They had one child together, a son named Matthew.

Return to Portland

In 1949 Art returned to Oregon. He seems to have sought work as a pilot, as suggested by his getting a second-class commercial medical on September 20, 1950,xliii but was apparently unsuccessful. He did land a job with the postal service, and worked there until retirement. According to Mr. John Johnson, a co-worker, Art worked swing shifts in the letter-sorting section of “Zone 19” of the Portland post office. This was a “bid” job, which implies that it was desirable. He remembers Art as friendly, sociable, and even then fond of flirting with attractive women.xliv However, it appears that he may have chosen a night shift due to self-consciousness, according to Craig Chinn: “He was always conscious of people staring at him so he preferred to work the late night shift at the Post Office.”xlv

Mr. Chinn also recalls that “Uncle Art always seemed like a strong, tough guy to me. We saw them often along with Gilbert, Steve, Susie and Matthew when we traveled as kids to [Art‘s home in] Portland (on 3 acres off Idyllwild). John has a picture of Susie (his mother), my sister Dale, myself, my brother Allan and John’s uncle Matthew eating watermelon. Their dog Rusty is watching us. Each time we visited it would take Rusty a few days to get used to us and to allow us to get close to him. That was Uncle Art’s guard dog since he was not home at night.”xlvi

His daughter Susan (“Susie”) remembers that he was very fond of “smoking a pipe. He always had a pipe in his mouth whether he was actually smoking it or not. He had a special tobacco mix which he smoked. He ordered it from a shop in New York City. He came to use this shop since World War 2 when he was undergoing all of his surgeries. I always associated this tobacco scent to him. I managed to hang onto one of his favorite pipes . . . he is photographed in uniform with this particular pipe. As a child he always made me clean his pipes. I rather enjoyed this particular chore because he had such an interesting array of pipes from all over the world. There was one in particular where the bowl of the pipe was hand carved out of ivory. I believe that pipe came from India. My mother gave away all of his pipes!!!! I can’t believe it!!! I used to roll cigarettes for my father as well. And, he loved a good cigar.”xlvii

Overseas Chinese, Chinese-American?

Not long before his death Art was asked by a newspaper reporter why he had gone. His response was “China called me.”xlviii This begs any number of questions, and can be best understood by exploring how Chinese expatriates and their descendants relate to China.

The status of an Overseas Chinese can be seen as of a perpetual foreigner; the individual is seen in their country of residence as linked with China, and in China as linked with their country of residence. As touched on earlier Art and his colleagues were unable to sign on with the Chinese national air force, despite the country’s desperate straits and clear need for trained pilots. This was also despite an outreach program (that is still in existence) that had been in operation since 1926.xlix It appears that although the KMT sought the support of Overseas Chinese it preferred to keep them at arm’s length and had very definite ideas about what form the support should take, e.g. funds and publicity. A group of eager young quasi-foreigners who appeared out of nowhere, speaking Cantonese (some of them badly) and falling over themselves begging to be thrust into harm’s way, apparently did not fit the profile.

The other side, in Art’s case, was not so visible, at least at the time. Although contemporary US accounts often describe him as an Oregon native, they also call him Chinese. For example, a September 6, 1944 newspaper article in The Oregonian about Art preparing to return to China was titled “Chinese Set to Go Back.”l In his high-profile bond drives Art wore a Chinese Air Force Major’s uniform and served, in essence, as a charismatic spokesman for China. With China and the US as wartime allies this was not a problem. However, when the interests of China and the US diverge it certainly can be, as several more recent cases in the United States illustrate.

Relating this back to Art and why he went, in his late teens he would almost certainly have been feeling that characteristic surge of idealism and optimism of youth. The tragic events in China were widely publicized and deplored, and as a youngster of Chinese heritage he would have been both better-informed and more strongly motivated than most to do something about it. His decision was not in isolation, either; he went in the company of a dozen of his peers, one of whom, Clifford Louie Yim Qun, ended up (many years later) as a General in the Republic of China’s Air Force,li and another of whom, Hazel Ah Ying Lee died serving as a Women’s Air Service Pilot in the USAAF.lii

Having gone, why did he stay, through all the tragedy, horror and pain? How did he carry on, head high through everything that was thrown at him?

That would have to be something internal to Art, not external, not exclusive to any particular ethnic group, and not easily quantifiable. Let’s call it “character.”

With Art’s credentials as a hero in China well established, what about the American side of the equation? Although a native-born US citizen, he distinguished himself while serving with the armed forces of China, which would seem to disqualify him. However, there are a few wrinkles in this picture. Prominent among them is the fact that other Americans were also serving with foreign air forces. By the time of Pearl Harbor the war in Europe had been raging for over two years and in China for four. On December 7, 1941, Americans were flying with the RAF and RCAF in Europe (most notably with the three Eagle Squadrons) and the American Volunteer Group was on the verge of operational capability in China and Burma. Speaking of the latter, the AVG was actually formed and, soon after the Pearl Harbor attack, operated, as a unit of the national Chinese air force — the famous Flying Tigers. Certainly most US historians would be loath to disown the Flying Tigers on that basis alone.

Another is that he may have been among America’s first aces of World War 2. Strictly speaking, after the US entered the war the first Army AF ace was Lt Boyd D. “Buzz” Wagner and the first Navy ace was Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare.liii Within this boundary the picture is fairly clear, but looking beyond it things become more complicated. If we’re willing to include the contributions of Americans serving before this time then, besides Art and his colleagues in China, we need to look at pilots such as Frank Tinker and “Ajax” Baumler who served in the 1936 to 1939 Spanish Civil War. And indeed, Frank Tinker claimed his fifth confirmed victory on June 16th, 1937, about two months before Art Chin shot down his first.liv However, (not to minimize their accomplishments) Spain was officially neutral during World War 2 while China was both an ally and a theater of operations. And although it can he said that the enemy in Spain was, in the larger sense, the same Fascism the US later had to deal with in the form of Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, the enemy Art Chin faced in 1937 was unambiguously the same as the one that bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 – the armed forces of the Empire of Japan. It would appear, then, that Art is as much an American hero as a Chinese one.

Although it hasn’t been widely publicized, authorities in the US seem to have accepted this view. Recognition for some of Art’s accomplishments came on February 28, 1995 when the US Air Force awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal for his flights over the “Hump.”lv He passed away on September 7, 1997, less than a month before he was inducted into the American Combat Airman Hall of Fame of the Commemorative Air Force Airpower Museum in Midland, Texas.lvi Over 3,000 people, including Vivienne, attended the ceremony on October 4th. More recently, on March 5, 2008, the US Congress approved legislation to name a post office in Beaverton, Oregon, the “Major Arthur Chin Post Office Building.”

Final Thoughts

Although the once-popular myth that the Flying Tigers fought “for years” before Pearl Harbor has been largely dispelled, it has not been replaced by an awareness that Americans did serve in the air war over China during the ’30s. Some became aces before the U.S. even entered the war. Many stayed on and continued to contribute to the Allied effort, joined by more of their countrymen. One of these was Arthur “Art” Chin, whose courage and dogged tenacity in the face of adversity shines as an example to us all. His story is a shared piece of Chinese and United States aviation and military history, and his legacy should be shared as well.

SOURCES:

Books

Bowers, Peter. Boeing P-26 Variants. Arlington, TX: Aerofax, 1984.

Chennault, Claire Lee. Way of a Fighter. Tucson: James Thorvardson & Sons, 1991.

Francillon, Rene J.. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Gott, Kay. Hazel Ah Ying Lee, Women Air Force Service Pilot. Eureka, CA: Veterans Quality Printing, 1996.

Olynyk, Frank. Stars and Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973. London: Grub Street, 1995.

Roberts, J. A. G.. A Concise History of China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Seagrave, Sterling. The Soong Dynasty. New York: Harper & Row, 1985.

Tunner, William H. Over the Hump. Washington DC: Office of Air Force History, 1985.

Xu, Guangqiu. War Wings: the United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929-1949. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001.

Articles

“Chinese Heroes of the Skies,” The Oregonian 1995(?): p. A1.

“Chinese Set to Go Back.” The Oregonian 06 Sep 1944: pp. 2-1, 2-2.

Cole, William. “’Hump over Himalayas Yields Human Remains.” Honolulu Advertiser 28 Oct 2002.

Louie, D.Y.. “Chinese Air Force Gladiators in Action.” Small Air Forces Observer December 1998: pp. 118-121.

Louie, D.Y.. “Chinese American Aces in the Chinese Air Force.” Small Air Forces Observer July 1996: pp. 55-56.

Shevchuk, Dmitry. “Soviet Planes and Pilots in China.” Small Air Forces Observer October 1997: pp. 86-87.

Websites

Fisler, Jody. “A Castle in the Air: The William and Mary Flight School.” Higher Education in Review 2005. //www.clubs.psu.edu/up/hesa/HER/v2/Castle.pdf . 28 Oct 2007. (p. 42)

Gustavsson, Hakan. “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007 //surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/china_chin.htm

Lam, C. W. “Insignia of China.” 1 Oct 2007. 3 Dec 2007.

“Major Arthur T. Chin, Chinese Air Force,” American Combat Airmen Hall of Fame. 1997. 9 Dec 2007. //www.airpowermuseum.org/exhibits/acahof/assets/pdf/1997/chin.pdf

“Overseas Chinese.” Wikipedia. 03 Dec 2007. 09 Dec 2007. //en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overseas_Chinese

Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission-About (2001 December 07). Retrieved December 9, 2007, from Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission Web site: //www.ocac.gov.tw/

“Wu Tingfang.” Wikipedia. 01 Dec 2007. 05 Dec 2007. //en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Tingfang

Interview

Mr. John Johnson. Telephone interview. 30 Sep 2007.

Footnotes:

i – Jody Fisler, “A Castle in the Air: The William and Mary Flight School.” Higher Education in Review 2005, (A copy of this can be downloaded here.) 28 Oct 2007, p. 42. The actual rates for the Al Greenwood school are not available, but to compare, at the William and Mary Flight School in 1931 the total cost of the course leading to a pilot’s license was $300, which included ground school and 20 hours of flight time (the minimum to meet license requirements). This may have been something of a bargain: other sources give $15 per hour as the going rate for flight instruction alone.

ii – Kay Gott, Hazel Ah Ying Lee, Women Air Force Service Pilot (Eureka, CA: Veterans Quality Printing, 1996) p. 96.

iii – J. A. G. Roberts, A Concise History of China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003) pp. 217-228.

iv – C.W. Lam, “Insignia of China.” 1 Oct 2007. 3 Dec 2007.

v – Guangqiu Xu, War Wings: the United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929-1949. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001) pp. 90-91.

– C. W. Lam, “Insignia of China.” 1 Oct 2007. 3 Dec 2007.

vi – Frank Olynyk, Stars and Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (London: Grub Street, 1995) pp. 192-193.

vii – “Chinese Heroes of the Skies,” The Oregonian 1995(?): A1.

viii – Craig Chinn, email 30 Apr 2011.

ix – Guangqiu Xu, War Wings: the United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929-1949. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001) pp. 96-97.

x – Sterling Seagrave, The Soong Dynasty (New York: Harper & Row, 1985) pp. 290, 319-320, 346.

xi – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xii – Peter Bowers, Curtiss Navy Hawks (Carrolton, TX: Squadron/Signal Publications 1995) pp. 34-40.

xiii – “Airborne Hero Arthur Chin.” oh100.com. 20 Feb 2004. 8 Dec 2007 //www.oh100.com/tech/junshi/mjff/200202/20030402221.html

xiv – “Wu Tingfang,” Wikipedia. 01 Dec 2007. 05 Dec 2007

xv – Peter Bowers, Boeing P-26 Variants (Arlington, TX: Aerofax, 1984) pp. 3-4. The Chinese knew the Model 281 as the “248,” which was the Boeing company designation for the domestic P-26.

xvi – D.Y. Louie, “Chinese American Aces in the Chinese Air Force,” Small Air Forces Observer July 1996: p. 55.

xvii – Rene J. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987) pp. 350-357.

xviii – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xix – D.Y. Louie, “Chinese Air Force Gladiators in Action,” Small Air Forces Observer December 1998: p. 118.

xx – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xxi – Frank Olynyk, Stars and Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (London: Grub Street, 1995) pp. 192.

xxii – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xxiii – Claire Lee Chennault, Way of a Fighter (Tucson: James Thorvardson & Sons, 1991) p. 68.

xxiv – Rene J. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987) pp. 342-349.

xxv – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xxvi – Dmitry Shevchuk, “Soviet Planes and Pilots in China.” Small Air Forces Observer October 1997: pp. 86-87.

xxvii – Frank Olynyk, Stars and Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (London: Grub Street, 1995) pp. 192.

xxviii – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xxix – Hakan Gustavsson, “Chinese Biplane Fighter Aces – Major ‘Arthur’ ‘Art’ Chin Shui-Tin.” Hakan’s Aviation Page – Biplane Fighter Aces. 04 July 2007. 28 Oct 2007

xxx – “Chinese Set to Go Back.” The Oregonian 06 Sep 1944: p. 2-2.

xxxi – Claire Lee Chennault, letter dated 10 Jun 1942.

xxxii – “Chinese Set to Go Back.” The Oregonian 06 Sep 1944: 2-1.

xxxiii – Craig Chinn, email 30 Apr 2011.

xxxiv – Raymond Cheung, post as “snake” on China Defense Forum, 16 Feb 03. //www.china-defense.com/smf/

xxxv – Medical Certificate – Airmen (Second Class), USA Department of Commerce, Civil Aeronautics Administration, 28 Mar 1945.

xxxvi – P.T. Mow, letter dated April 9, 1945.

xxxvii – William H. Tunner, Over the Hump (Washington DC: Office of Air Force History, 1985) p. 43.

xxxviii – William Cole, “’Hump’ Over Himalayas Yields Human Remains,” Honolulu Advertiser, 28 Oct 2002.

xxxix – Authorized Check Pilot Certificate, Civil Aeronautics Administration, Ministry of Communications, Republic of China, 15 Oct 1947 – 14 Oct 1948.

xl – Airline Pilot License # 10011, Civil Aeronautics Administration, Ministry of Communications, Republic of China, 7 Feb 1948.

xli – Raymond Cheung, post as “snake” on China Defense Forum, 16 Feb 03.

xlii – Craig Chinn, email 30 Apr 2011.

xliii – Medical Certificate – Commercial Airmen (Second Class), USA Department of Commerce, Civil Aeronautics Administration, 20 Sep 1950.

xliv – John Johnson, Telephone interview, 30 Sep 2007.

xlv – Craig Chinn, email 30 Apr 2011.

xlvi – Craig Chinn, email 30 Apr 2011.

xlvii – Susan Ennis, Facebook message December 14, 2010.

xlviii – “Chinese Heroes of the Skies,” The Oregonian 1995(?): A1.

xlix – “Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission-About.” Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission. 07 Dec 2007. 09 Dec 2007.

l – “Chinese Set to Go Back.” The Oregonian 06 Sep 1944: 2-1, 2-2.

li – D.Y. Louie, “Chinese American Aces in the Chinese Air Force,” Small Air Forces Observer July 1996: pp. 55-56.

lii – Kay Gott, Hazel Ah Ying Lee, Women Air Force Service Pilot (Eureka, CA: Veterans Quality Printing, 1996) pp. 62-65.

liii – Frank Olynyk, Stars and Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (London: Grub Street, 1995) p. 615 and p. 479 respectively.

liv – Frank Olynyk, Stars and Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (London: Grub Street, 1995) pp. 594-595.

lv – Special Order GB-133 – Distinguished Flying Cross, and GB-132 – Air Medal, signed by Col Kevin A. Collins.

lvi – “Major Arthur T. Chin, Chinese Air Force,” American Combat Airmen Hall of Fame. 1997. 9 Dec 2007. //www.airpowermuseum.org/exhibits/acahof/assets/pdf/1997/chin.pdf

——————————————————————–

NOTE: This article represents the hard work of three authors: Andy Chan, John Gong and Michael Little. Michael’s bio can be found below, and bios for Andy and John will be supplied here:

Andy Chan

Andy Chan was born in the same province Art Chin’s family was from, and has been fascinated by his legend since college. Andy received his master’s degree from Portland State University and has been writing on China-related affairs for over 20 years. He is currently serving as an editor of China-defense.com.

John Gong

A graduate of the George Washington University, John Gong is currently the President and CEO of Shangren Inc, and recently retired from the United States Government after spending 25 years working in the US Congress. He is also Arthur Chin’s grandson and a custodian of his legacy.

Really enjoyed this article about “uncle Art”. It provided a greater insight into the man not just his exploits as an air ace.

Art was compact not just physically but mentally. Physically, his good looks always reminded me of the Hollywood actor, Gilbert Roland and while not particularly tall, he was powerfully built. His military experiences made him a very disciplined man, one who was always seemed confident in himself and what he was doing. To me, his war injuries, while certainly visible, didn’t detract from his self confidence. If there was a problem he didn’t see it as his. That is why my take on working the night shift at the post office differs from this article.

Art was a high energy person and, as I said, very disciplined. Their property at Idyllwild was also a source of additional employment/income. The property contained many holly trees which they (the whole family) tended and at the Christmas holiday season harvested for holiday decorations and shipped to various points in the United States. To accomplish this, Art had to be available during the daylight hours. He was a very resourceful person.

My admiration for uncle Art has never wavered.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and insights on his life story

I posted a link to your article on Arthur Chin on my blog on the Chinese Exclusion Act case tiles.

//chineseexclusionfiles.com/2017/05/01/virginia-wong-buried-at-national-cemetery-of-the-air-force-at-nanking-china/

Arthur “Art” Chin’s story is wonderful story, I read it with emotion. I was in the USAAF during the period of 1944-1946, I was drafted at a very young age. (after finishing high school) I was very lucky and am still in my ninetys.